Australia’s State of the Forests Report presents comprehensive information describing the many social, economic and environmental values of Australia’s forests to government and industry stakeholders and the broader community. It meets Australia’s formal national reporting requirements for forest information, and the data assembled for Australia’s State of the Forests Report are used to meet Australia’s international forest-related reporting requirements.

Australia’s State of the Forests Report is structured against the Montréal Process framework of seven criteria for sustainable forest management:

- Conservation of biological diversity

- Maintenance of productive capacity of forest ecosystems

- Maintenance of ecosystem health and vitality

- Conservation and maintenance of soil and water resources

- Maintenance of forest contribution to global carbon cycles

- Maintenance and enhancement of long-term multiple socio-economic benefits to meet the needs of societies

- Legal, institutional and economic framework for forest conservation and sustainable management.

Within each criterion, various indicators (44 in total) address specific forest aspects and values. Individual indicators can be read as stand-alone reports by readers interested in particular aspects of Australia’s forests and their management. Key information is reported for each indicator, along with Supporting information as needed. Case studies are presented within some indicators as illustrations and to provide regional information.

The set of 44 indicators used for reporting in Australia was adapted from the broader list of Montréal Process indicators to better suit the unique characteristics of Australian forests, the goods and services they provide and the people who depend on or use them.

Australia’s State of the Forests Report (SOFR) is now a web-based product via rolling updates to the 44 indicators. Every five years a SOFR Synthesis will present an overview of the state of Australia’s forests, continuing the five-yearly reporting of SOFR that commenced with the first report in 1998.

Australia’s State of the Forests Report implements commitments in the National Forest Policy Statement (1992) and the Commonwealth Regional Forest Agreements Act 2002 to report comprehensively and publicly on all of Australia’s forests. It also provides the data for Australia’s international forest reporting requirements which include reporting through the Global Forest Resources Assessment led by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO), the UN State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources, the Global Forest Goals of the UN Strategic Plan for Forests, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

The definition of forest used in Australia, including for Australia’s State of the Forests Report, is the same as that used in Australia’s National Forest Inventory, and in all previous editions of Australia’s State of the Forests Report:

An area, incorporating all living and non-living components, that is dominated by trees having usually a single stem and a mature or potentially mature stand height exceeding 2 metres and with existing or potential crown cover of overstorey strata about equal to or greater than 20 per cent. This includes Australia’s diverse native forests and plantations, regardless of age. It is also sufficiently broad to encompass areas of trees that are sometimes described as woodlands.

Under this definition, large expanses of tropical Australia where trees are spread out in the landscape are forest, as are many of Australia’s multi-stemmed eucalypt mallee associations. What many people would typically regard as forests – stands of tall, closely spaced trees – comprise a relatively small part of the country’s total forest estate. Much of Australia’s open and woodland forests are available for grazing.

Australia’s definition of forest uses the phrases ‘mature or potentially mature’ with regard to stand height, and ‘existing or potential’ with regard to crown cover. Use of these phrases allows forest areas that have temporarily lost some or all trees (for example, as a result of bushfires, cyclones or wood harvesting) to be identified as part of the forest estate.

Areas identified by the Australian Collaborative Land Use and Management Program as urban and industrial land, land under horticultural land use (such as orchards), and land under intensive agricultural uses, even if they include trees, are not included as forest.

The geographic scope of Australia’s State of the Forests Report is the extent of forests mapped by Australia’s National Forest Inventory. This includes forests in all Australia’s states and mainland territories and their close offshore islands, but not external territories such as Norfolk Island, Lord Howe Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Christmas Island.

Australia’s forests are highly valued for a wide range of environmental, social and economic benefits and services, including:

- supporting a rich biodiversity

- providing clean water and soil protection

- maintaining cultural, heritage and aesthetic values

- providing recreation, tourism, scientific and educational opportunities

- providing wood and non-wood products.

Australia’s forests occur across a broad range of geographic landscapes and climatic environments, and contain many species that occur naturally only in Australia or in a particular region within Australia. These characteristics combine to form unique and complex ecosystems.

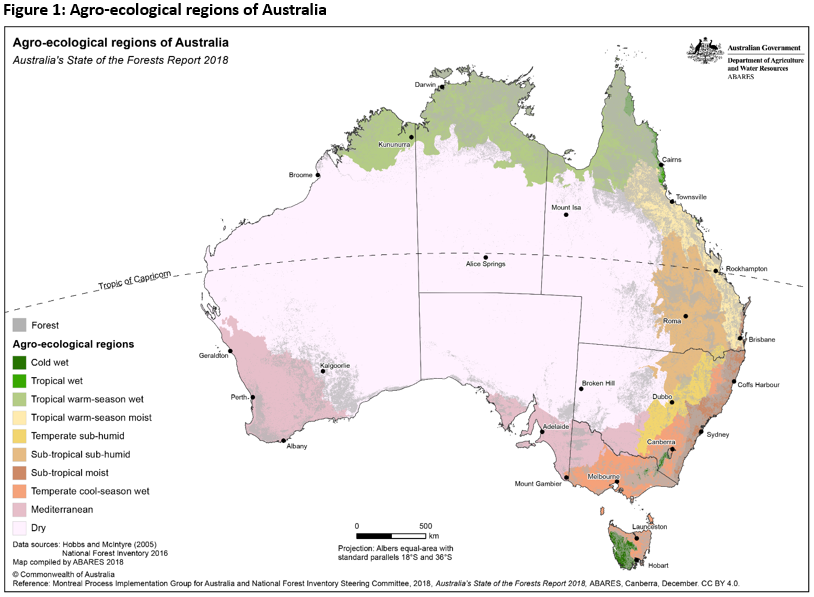

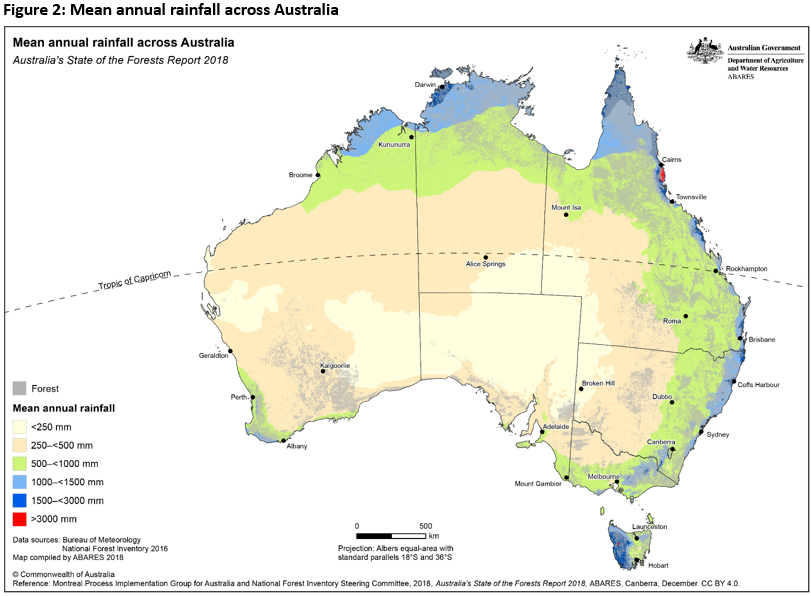

Forests extend across the continent’s northern tropical regions, along the east coast through sub-tropical regions to temperate cool-season wet and cold wet zones in the south-east; and in the Mediterranean climate zones of the south-east and south-west (see Figure 1). In some regions, forests extend from the wetter, coastal and sub-coastal areas into central, drier parts of the continent (Figure 2). Through these regions, forests grow on soils that vary from ancient, fragile and infertile, to more recently formed, fertile soils of alluvial and volcanic origin.

Australia’s forests are assigned to three broad categories in Australia’s National Forest Inventory, with each category divided into various forest types (see Indicator 1.1a):

- ‘Native forests’, which are divided into eight national native forest types named after their key genus or structural form: Acacia, Callitris, Casuarina, Eucalypt, Mangrove, Melaleuca, Rainforest, and Other native forest. Across the wide range of rainfall and soil conditions that support forest, more than 80% of Australia’s native forests are dominated by eucalypts and acacias.

- ‘Commercial plantations’, which are hardwood and softwood plantations grown and managed for wood production to supply logs to wood-processing industries for the manufacture of wood products.

- ‘Other forest’, which comprises small areas of mostly non-commercial plantations and planted forests of various types, including plantations of sandalwood (Santalum spp.), some smaller farm forestry and agroforestry plantations, environmental plantings, plantations within the reserve system, and plantations regarded as not commercially viable. Non-planted forest dominated by introduced species are also included in the Other forest category.

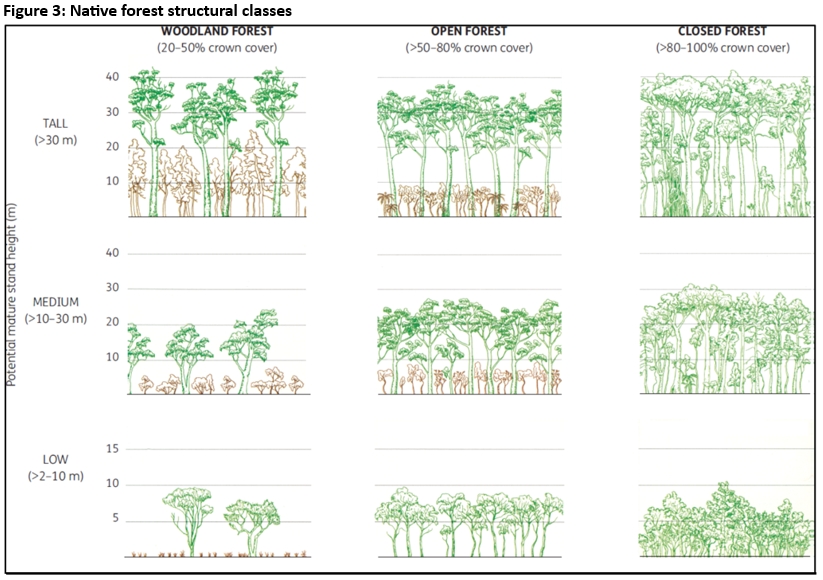

Australia’s native forests are classified into structural classes based on combinations of crown cover, stand height and form, to provide a better understanding of their characteristics (Figure 3).

In terms of crown cover, the above image shows:

- ‘Closed forest’ is forest where the tree canopies cover more than 80% of the land area.

- ‘Open forest’ is forest where the tree canopies cover between 50% and 80% of the land area.

- ‘Woodland forest’ is forest where the tree canopies cover between 20% and 50% of the land area.

Land with trees where the tree canopies cover less than 20% of the land area is not classified in Australia as forest, but is categorised as various forms of non-forest vegetation.

In terms of stand height, the above image shows:

- ‘Tall forest’ is forest with a stand height greater than 30 metres.

- ‘Medium forest’ is forest with a stand height between 10 and 30 metres.

- ‘Low forest’ is forest with a stand height greater than 2 metres and up to 10 metres.

In terms of tree form (not shown in Figure 3):

- ‘Eucalypt mallee’ forests contain multi-stemmed trees.

The majority of Australia’s native forest area is dominated by evergreen, broadleaf, hardwood tree species. For national reporting, Australia’s native forests are classified into eight broad forest types defined by dominant species and structure. These eight forest types are:

Acacia

Australia has almost 1000 species of Acacia, making it the nation’s largest genus of flowering plants. Commonly called wattles, Acacia species are remarkably varied in appearance, habit and location, from spreading shrubs to trees that are more than 30 metres tall. See the Acacia forest profile for more information.

Callitris

The genus Callitris comprises 15 species, of which 13 occur in Australia. Callitris trees are commonly called cypress pines because they are related to, and resemble, Northern Hemisphere cypresses; they are not true pines. See the Callitris forest profile for more information.

Casuarina

The family Casuarinaceae occurs naturally in Australia, south-east Asia and the Pacific region. The forest type Casuarina includes forests dominated by species of either Casuarina (6 species in Australia) or Allocasuarina (59 species in Australia). See the Casuarina forest profile for more information.

Eucalypt

Eucalypt forests are by far the continent’s most common forest type, covering about three-quarters of Australia’s native forest estate and occurring in all but the continent’s driest regions. The term ‘eucalypt’ encompasses approximately 800 species in the three genera Eucalyptus, Corymbia and Angophora, with almost all of these species native to Australia.

For national reporting, the Eucalypt forest type is divided into 11 forest subtypes based on the form of dominant individuals (multi-stemmed mallee or single-stemmed tree), height of mature trees (low, medium or tall) and crown cover (closed, open or woodland).

See the Eucalypt forest profile for more information.

Mangrove

Although comprising less than 1% of Australia’s forest cover, mangrove forests are an important and widespread ecosystem. They are found in the intertidal zones of tropical, subtropical and sheltered temperate coastal rivers, estuaries and bays, where they grow in fine sediments deposited by rivers and tides. See the Mangrove forest profile for more information.

Melaleuca

The genus Melaleuca contains more than 200 species, most of which are endemic to Australia. Only a few species develop the required community structure and height for stands to be classified as forests; these taller species are known as teatrees or paperbarks. See the Melaleuca forest profile for more information.

Rainforest

Australia’s rainforests are characterised by high rainfall, lush growth and closed canopies. They rarely support fire, and generally contain no eucalypts or only occasional individual eucalypts as emergent trees above the rainforest canopy. There are many types of rainforest in Australia, varying with rainfall and latitude. See the Rainforest profile for more information.

Other native forest

The ‘Other native forest’ type includes a range of minor native forest types each named after its dominant genus, including Agonis, Atalaya, Banksia, Hakea, Grevillea, Heterodendron, Leptospermum, Lophostemon and Syncarpia, as well as native forests where the type is unknown.

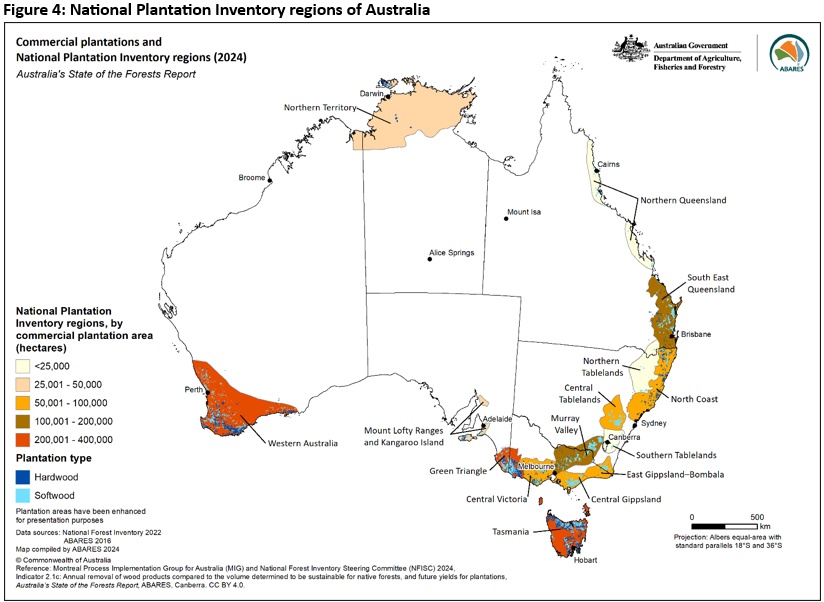

Commercial plantations are intensively managed stands of trees of either native or exotic species, created by the regular placement of seedlings or seeds. Australia’s commercial plantations comprise both softwood and hardwood species managed for the purpose of commercial wood production (predominantly sawlogs and pulplogs) for domestic and international markets. They are usually grown over set rotations, defined as the planned number of years between establishment of a stand of trees, and final harvesting. Commercial plantations produce most of the volume of logs harvested annually in Australia. Non-commercial plantations and other planted forests are reported in the ‘Other forest’ category.

Fifteen plantation regions are used by the National Plantation Inventory to represent economic wood supply zones (Figure 4), including five regions spanning a state or territory border.

The ownership or tenure of forest land, especially native forest, has a major bearing on its management. Different types of ownership are linked to who has the right to use and occupy land, the right to use forest resources, and the conditions that may be attached to these rights.

The six national land tenure classes used to classify land in the National Forest Inventory are as follows:

- Leasehold forest: Crown land held under leasehold title, and generally privately managed, although state and territory governments may retain various rights over the land, including over forests or timber on the land. This class includes land held under leasehold title with special conditions attached for designated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (referred to collectively as Indigenous communities in Australia’s State of the Forests Report).

- Multiple-use public forest: publicly owned state forest, timber reserves and other land, managed by state and territory government agencies for a range of forest values, including wood harvesting, water supply, biodiversity conservation, recreation and environmental protection.

- Nature conservation reserve: publicly owned lands managed by state and territory government agencies that are formally reserved for environmental, conservation and recreational purposes, including national parks, nature reserves, state and territory recreation and conservation areas, and some categories of formal reserves within state forests. This class does not include informal reserves (areas protected by administrative instruments), areas protected by management prescription, or forest areas pending gazettal to this tenure. The harvesting of wood and non-wood forest products generally is not permitted in nature conservation reserves.

- Other Crown land: Crown land reserved for a variety of purposes, including utilities, scientific research, education, stock routes, mining, use by the defence forces, and to protect water-supply catchments, with some areas used by Indigenous communities.

- Private forest: land held under freehold title and private ownership, and usually privately managed. This class includes land with special conditions attached for designated Indigenous communities.

- Unresolved tenure: land where data are insufficient to determine land ownership status.

All land in each state and territory is allocated by ABARES to one of these six tenure classes using state, territory and national datasets of land titles and land tenure, then intersected with the national forest coverage to determine the areas of forest land in each tenure class.

These six national tenure classes are amalgamations of the wide range of classes used by various state and territory jurisdictions. The classes can be grouped based on land ownership as public or private, with a small area of unresolved tenure. Publicly owned tenures include ‘multiple-use public forest’, ‘nature conservation reserve’ and ‘other Crown land’. ‘Leasehold forest’ is Crown land (land that belongs to a national, state or territory government) that is privately managed, although state and territory governments may retain various rights over the land, including over forests or timber on the land. Some forests on private land are publicly managed as conservation reserves, for example Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory. For commercial plantations, the ownership of the land can be different from ownership of the trees, and management arrangements can be complex.

Preferences in terminology when referring to Australia’s First Peoples vary across Australia, and have changed over time. Consideration of Indigenous peoples in Australia’s State of the Forests Report and associated products is inclusive of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities. The term Indigenous peoples and communities is also used for consistency in the titles of indicators, datasets, programs or reports, including Australia’s framework of criteria and indicators; this usage originated at the time this framework was published (2008).

Australia has three levels of government:

- Commonwealth or federal (also referred to as the Australian Government or the national government);

- state and territory; and

- local (city-based or regionally based).

The term ‘jurisdiction’ denotes any of the nine jurisdictions in Australia, being the six states, two territories and the Commonwealth of Australia.

Australia’s state and territory governments have responsibility for land allocation and land management, including forest management. The Australian Government has limited forest management responsibilities, but may influence management through legislative powers associated with foreign affairs (particularly treaties and international agreements), commodity export licensing, taxation, and biodiversity conservation, and through targeted spending programs to meet environmental, social or economic objectives. Such programs are generally developed cooperatively with state and territory governments. Australia’s forest policy, together with the management of Australia’s forests, is guided by the National Forest Policy Statement (1992), signed jointly by the Australian Government and state and territory governments.

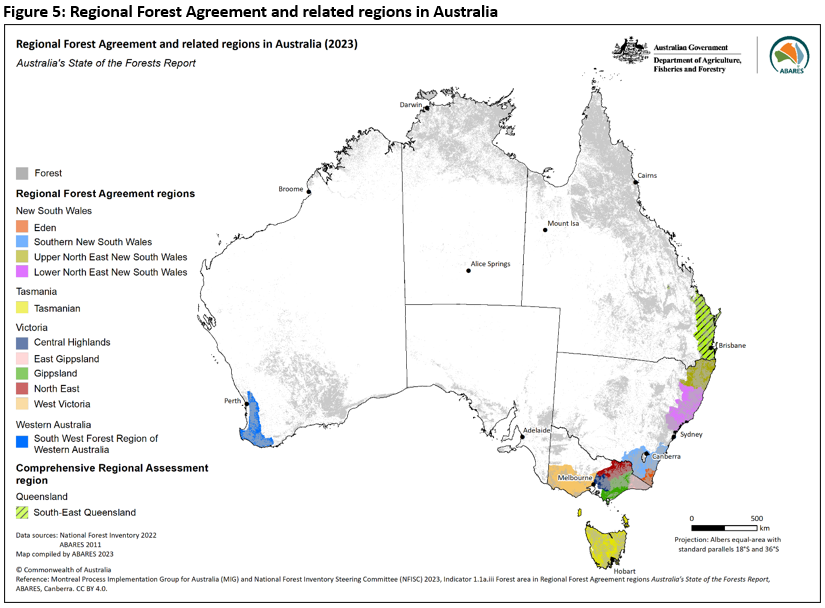

Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) are long-term agreements for the conservation and sustainable management of specific regions of Australia’s native forests, and resulted from substantial scientific study, consultation and negotiation with a diverse range of stakeholders. Science-based methodologies and Comprehensive Regional Assessments (CRAs) were used to determine forest allocation for different uses and to underpin forest management strategies. The RFAs were designed to provide certainty for forest-based industries, forest-dependent communities and nature conservation. Certain obligations of the Commonwealth under RFAs were given effect through the Commonwealth Regional Forest Agreements Act 2002.

Ten RFAs covering 11 regions were negotiated between the Australian Government and the New South Wales, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia State Governments (Figure 5), as a key outcome of the National Forest Policy Statement (1992). The Australian and Queensland governments also completed a CRA for south-east Queensland, however an RFA was not signed.

Davey (2018) describes the origins and development of Australia’s RFAs.

Sustainable forest management seeks to achieve environmental outcomes, promote economic development, and maintain the social values of forests, to meet the needs of society without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.

This approach reflects the principal objectives of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), to which Australia is a signatory – namely, the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from its use. The CBD recognises that the key to maintaining biological diversity is using it in a sustainable manner (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity 2005). Sustainably managed forests thus maintain a broad range of values into the future, and the Australian, state and territory governments have a range of processes to help meet this goal.

Criteria and indicators provide a common understanding of the components of sustainable forest management, and a common framework for describing, assessing and evaluating progress towards sustainable forest management. The criteria represent broad forest values that society seeks to maintain, while the indicators describe measurable aspects of those criteria (MIG 1998). The framework of criteria and indicators for sustainable forest management developed by the international-level Montréal Process Working Group on Criteria and Indicators for the Conservation and Sustainable Management of Temperate and Boreal Forests was adopted in Australia in 1998. Development and application of these criteria and indicators in Australia occurs through the Montreal Process Implementation Group for Australia (MIG).

As with the international Montréal Process, Australia’s framework includes the following seven criteria:

- Conservation of biological diversity

- Maintenance of productive capacity of forest ecosystems

- Maintenance of ecosystem health and vitality

- Conservation and maintenance of soil and water resources

- Maintenance of forest contribution to global carbon cycles

- Maintenance and enhancement of long-term multiple socio-economic benefits to meet the needs of societies

- Legal, institutional and economic framework for forest conservation and sustainable management.

Australia’s State of the Forests Report is the result of collaboration among the Australian, state and territory governments, led by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) within the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, and coordinated by the National Forest Inventory Steering Committee (NFISC) and the Montreal Process Implementation Group for Australia (MIG).

ABARES requests data from each of the states and territories to populate the 44 indicators of Australia’s State of the Forests Report. Based on responses to these requests and information obtained from national agencies and other sources, ABARES prepares summary tables, figures and text for each indicator, paying particular attention to changes and trends over time. The state and territory governments, through the MIG and the NFISC, and officers from Australian government agencies, are invited to participate in a drafting group to review manuscripts and provide supplementary information. Draft indicators are reviewed and endorsed by the MIG and the NFISC.

The list of contributors can be found here.

Reporting on Australia’s forests via Australia’s State of the Forests Report (SOFR) is an online-first publishing approach outlined in the Position Paper on the proposed approach for Australia’s State of the Forests Report for 2023 and beyond. The online-first approach enables individual indicators to be updated on the Forests Australia website as new data become available, and replaces the previous process which updated and published all 44 indicators in a single report. The progressive update and publication of indicators will be accompanied by the publication of a five-yearly SOFR Synthesis with summaries of the best-available data in the 44 indicators at the time, thereby continuing the five-yearly cycle of reporting SOFR since 1998.