This indicator measures the harvest levels of wood products in relation to future yields. The capacity to implement strategies to deal with changing demand for forest products based on future yields from both native and plantation forests is an integral part of sustainable forest management.

This part of Indicator 2.1c: Annual removal of wood products compared to the volume determined to be sustainable for native forests, and future yields for plantations, published October 2024, presents the calculated sustainable yields and actual harvested wood volumes of sawlogs from multiple-use public native forests, and the supplementation of sawlogs from hardwood plantations.

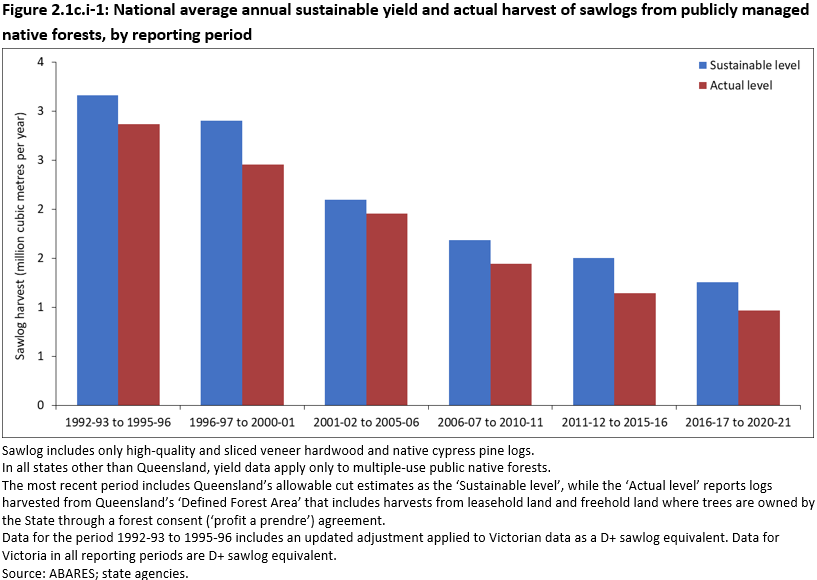

- An average annual volume of 0.97 million cubic metres of high-quality sawlogs was harvested from multiple-use public native forests and other native forests where timber is owned by the Crown, during the period 2016-17 to 2020-21. Nationally, this was 23% below the calculated sustainable yield across this period, and within the allowable harvest levels in the states where harvesting occurred in publicly managed native forests: New South Wales, Tasmania, Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia. There is no native timber harvesting in the Australian Capital Territory and South Australia, and there is no multiple-use public forest in the Northern Territory.

- The average annual sustainable yield of high-quality sawlogs from multiple-use public native forests declined nationally by 16% since the 2011-12 to 2015-16 period, and by 25% since the 2006-07 to 2010-11 period, due to the transfer of areas of multiple-use public native forest to nature conservation reserves, increase in the area of harvest restrictions, revised forest growth and yield estimates, and impacts of intense broad-scale bushfires.

The concept of a sustainable level of forest production is that long-term environmental values and the productive capacity of forests are not compromised while providing for society’s immediate needs. This applies to both wood and non-wood products.

A sustainable timber yield is calculated as the volume of wood (usually higher-grade sawlogs) that can be removed each year from an area of forest while ensuring maintenance of the functioning of the native forest system as a whole and the supply of the same range of wood products in similar proportions in perpetuity. States in which native forest harvesting on public land occurs have formal processes, backed by regulatory frameworks (such as legislation, management plans, codes of practice and policy), that inform calculation of sustainable sawlog yields for publicly managed native forests (primarily multiple-use public forests).

State agencies in New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia that manage multiple-use public native forests for wood production have been forecasting sustainable yields for many decades, with national reporting of sustainable yield commencing in Australia’s State of the Forest Report 1998. The sustainable yield of wood products from native forest is usually calculated based on the production of high-quality products, with the quantity of wood harvested constrained so that future harvesting can occur on a non-declining yield basis. The systems used by state agencies to calculate future wood supply are periodically independently reviewed to support the validity of estimates (Brack and Vanclay 2011; Brack 2017).

The harvesting of wood products from native forests is not permitted in the Australian Capital Territory and South Australia. The Northern Territory has no multiple-use public forests. Data presented in this indicator are current to 2020-2021 and do not take into account the subsequent announcements to end some native wood harvesting in Victoria and Western Australia.

The quality and availability of log types from native forests vary depending on the forest type and species mix, and previous disturbance factors such as fire and harvesting.

High-quality hardwood sawlogs are graded to utilisation standards developed and used by state agencies, and are typically used for flooring, decking, cladding, panelling, furniture making and appearance grade structural timber.

Other high-quality hardwood log products include poles, piles, girders and other solid logs.

Native softwood sawlogs are cypress (Callitris spp.) pine sawlogs and are classed as high-quality or low-quality in New South Wales, and sawlog-grade in Queensland. Cypress pine sawlogs are typically used for flooring, house framing, cladding and joinery.

Low-quality sawlogs, pulplogs and other wood products are also harvested from native forest, usually as a residual product arising from the harvest of high-quality logs. Sustainable yields are generally not determined for these other products.

Miscellaneous wood products such as firewood, fuelwood, sleeper logs and fencing materials are also produced from Australia’s native forests.

Sustainable sawlog harvest volumes are calculated using data on forest type and age-class, standing wood volumes, terrain, accessibility, tree growth and yield, and net harvestable area. Calculations account for restrictions on harvesting imposed by codes of practice and other regulation, and risks associated with fire, disease, storm damage and aspects of climate change.

Sustainable harvest volumes will vary over time due to changing forest management strategies, changes to the net harvestable area and the availability of improved resource data. Thus, sustained yield calculations are reviewed periodically by forest scientists. Annual harvesting levels may fluctuate around sustainable volume, with overcuts in some years balanced by undercuts in others, to average a net harvest volume that is less than the sustainable yield level.

Due to the transfer of substantial areas of multiple-use public forest to nature conservation reserves over the last 30 years (Davey 2018, Jacobsen et al. 2020), several states have implemented transitional long-term sustainable wood supply strategies aimed at limiting disruption to the forest industry. These strategies included supplementation of public native forest wood with high-quality wood resources from public plantations, and from the purchase of private forests or logs from private forests. The harvest from public native forests under these long-term supply strategies is considered sustainable because they are designed to maintain the productive capacity of native forests to produce wood in perpetuity on a non-declining yield basis after a specified transition period.

An annual average of 0.97 million cubic metres of high-quality sawlogs were harvested nationally from publicly managed native forests during the period 2016-17 to 2020-21 (Figure 2.1c.i-1). This continued the progressive decline from 1.96 million cubic metres in the 2001-02 to 2005-06 period, 1.44 million cubic metres in the 2006-07 to 2010-11 period, and 1.14 million cubic metres in the 2011-12 to 2015-16 period. The national level of actual harvest volume for 2016-17 to 2020 21 was 23% below the calculated sustainable yield. The decrease in actual annual harvest volumes over the six periods is consistent with the decrease in sustainable yields (Figure 2.1c.i-1).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1c.i-1.

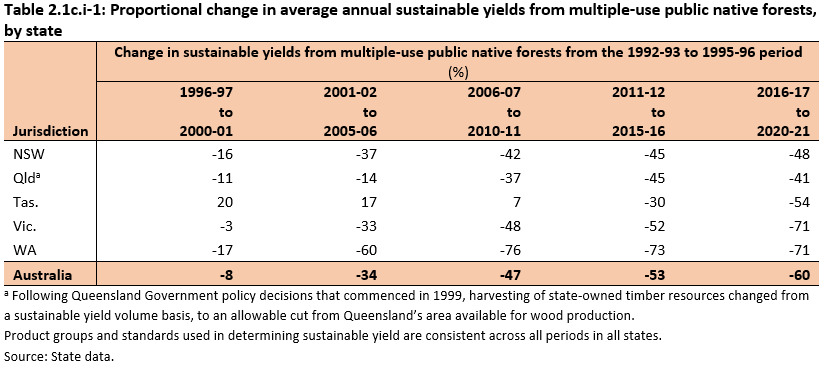

For the period 2016-17 to 2020-21, the national average annual sustainable yield from publicly managed native forests declined by 60% from that in the 1992-93 to 1995-96 reporting period. Declines ranged from 41% to 71% across the five states where harvesting occurred in publicly managed native forest (Table 2.1c.i-1). These declines have been due to:

- the transfer of multiple-use public native forests into nature conservation reserves, which reduced the area of native forest available for wood harvesting (see Davidson et al. 2008, Jacobsen et al. 2020)

- increased restrictions on wood harvesting in codes of practice and other regulatory instruments

- revised estimates of growth and yield due to improved resource information and incorporation of projected climatic effects on future forest growth

- the impacts of intense broadscale bushfires (FCNSW 2020; DJPR 2021).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 2.1c.i-1.

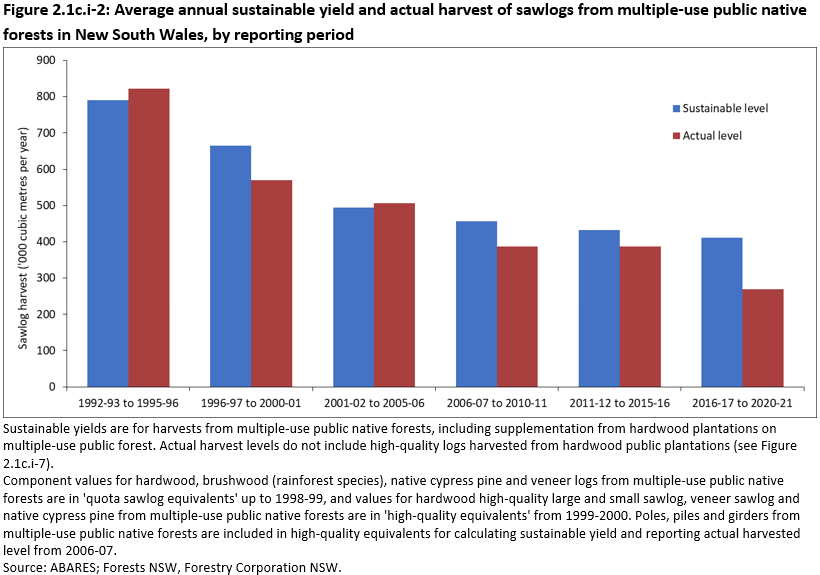

Across all states and all reporting periods, the average volumes harvested from publicly managed native forests were below the sustainable yield or allowable cut across all states and all periods, except for New South Wales in 1992-93 to 1995-96 and 2001-02 to 2005-06, and Queensland in 2006-07 to 2010-11 (Figures 2.1c.i-2 to 2.1c.i-6). ‘Allowable cut’ can be defined as the average quantity of wood, usually prescribed in a legislative instrument or an approved management plan, permitted to be harvested from a forest management planning unit or region, annually or periodically, under management for sustained yield. The specified allowable cut may be at, above, or below calculated sustainable yield levels depending on management objectives.

The actual average annual volume of high-quality sawlogs harvested in the period 2016-17 to 2020-21 was 269 thousand cubic metres, which was 37% below the calculated sustainable yield for the same period (Figure 2.1c.i-2). The average annual estimated sustainable yields have steadily declined since 1992-93.

The actual average annual volume harvested was slightly higher than the sustainable yield in two reporting periods (1992-93 to 1995-96 and 2001-02 to 2005-06), but was within allowable limits (Figure 2.1c.i-2). The regulations applicable to wood harvesting at the time permitted the forest management agency in New South Wales to harvest volumes above the sustainable yield in a particular year, provided this was balanced with undercuts in subsequent years. The net result was that volumes harvested were within the sustainable yield across a longer period.

The 2019-20 bushfires had a significant impact on the high-quality sawlog volumes harvested from New South Wales multiple-use public native forest. The high-quality sawlog yields for 2019-20 and 2020-21 were 226 thousand cubic metres and 138 thousand cubic metres, respectively. This compares with an average annual harvest of 328 thousand cubic metres for the years between 2016-17 to 2018-19. The post-bushfire reduction in harvest volumes was due to a range of direct and indirect factors including:

- interruption of harvesting operations due to approaching fire-fronts

- diversion of harvesting machinery and personnel to fire-fighting efforts

- disruption to harvesting schedules

- augmentation of existing protection measures (Coastal Integrated Forestry Operations Approval) with additional environmental safeguards in recognition of threatened species concerns

- increased safety risks

- substitution of multiple-use public native forest sawlog supply with supply from public hardwood plantations to help facilitate recovery in fire-impacted native forests.

Sustainable yields and log supply were calculated for multiple-use public native forests in all regions of New South Wales for a 100-year period, 2010 to 2110 (Forests NSW 2010). An updated wood supply forecast was undertaken for coastal regions in 2018 (NSW DPI 2018). This update estimated an average annual yield of 412 thousand cubic metres of high-quality sawlog from multiple-use public native forests in coastal regions over the modelled 100-year period. Supplementation from public-owned hardwood plantations, predominately in the state’s north-east, contributes to the wood supply.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1c.i-2.

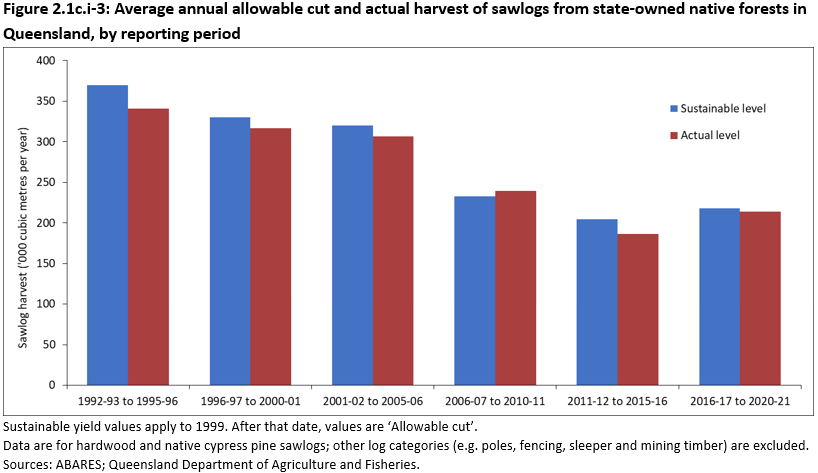

For the period 2016-17 to 2020-21, the actual average annual sawlog volume harvested in Queensland was 214 thousand cubic metres, which was 2% below the allowable cut of 218 thousand cubic metres for the same period (Figure 2.1c.i-3). Sawlog harvest volumes have steadily declined over all reporting periods (except the most recent period, 2016-17 to 2020-21), and have remained close to the sustainable yield (to 1999) and allowable cut levels (from 1999). The allowable cut and harvested volume of sawlogs in Queensland increased slightly in the 2016-17 to 2020-21 reporting period due to the under-cut in the preceding period.

In Queensland, the area available for wood production by the state (the Crown) comprises all State Forest and Timber Reserves, large areas of other Crown land (including leasehold land, Forest Entitlement Areas and unallocated state-owned land) and some freehold land over which the state retains ownership of forest products.

In 1999, the Queensland Government signed the South East Queensland Forests Agreement (SEQFA). This agreement, along with arrangements in other regions, aimed to eventually end wood production in public native forests in the south-east of the state, Queensland’s major wood-producing area. The intention was that these forests would subsequently be gazetted as protected area tenures.

At the commencement of the SEQFA, the Queensland Government also made a series of decisions on future harvesting levels and on reservation for nature conservation in other parts of the state. These decisions resulted in the exclusion of harvesting from additional areas of public native forest and are reflected in the sustainable yield volume (to 1999) and the allowable cut limit (from 1999) (Figure 2.1c.i-3). The systems used to forecast sustainable yield before 1999 are described in a 1998 report (Queensland Government 1998).

State-owned native timber production is scheduled to end in the South East Queensland Regional Plan area on 31 December 2024 (Queensland Government 2019). This area includes Brisbane, Moreton Bay, Lockyer Valley, Scenic Rim, Gold Coast, Redlands, Sunshine Coast and Noosa. The ending of state-owned native timber harvesting in South East Queensland impacts future national sustainable high-quality sawlog yields, as described in Indicator 2.1c.iii. State-owned native timber harvesting will continue in the Eastern Hardwoods region (including areas around Wide Bay and most of South Burnett) until 31 December 2026 while resource assessment work is undertaken to assist with decisions around future wood harvesting in that region. Long term supply commitments currently exist for permit holders in the Western Hardwoods region until 2034, and sales permits are in place for native cypress pine until 2037 (Queensland Government 2019).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1c.i-3.

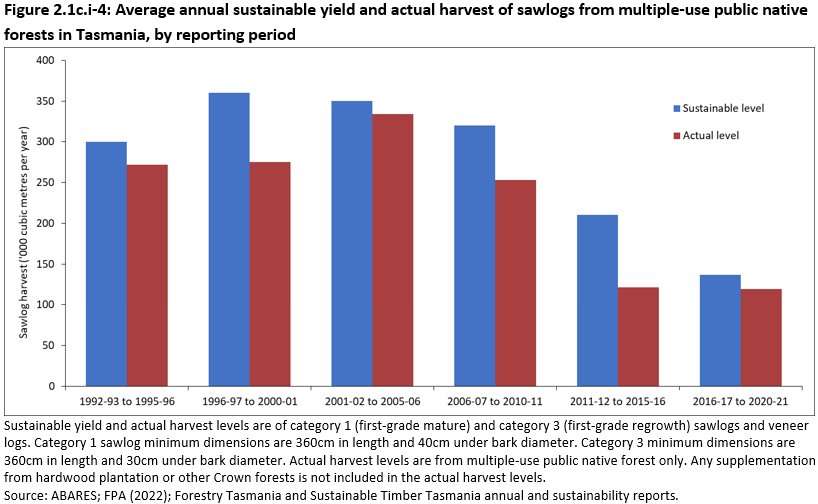

For the period 2016-17 to 2020-21, the minimum annual high-quality sawlog volume (the sustainable yield) for Tasmania was set at 137 thousand cubic metres. The actual average annual volume of high-quality sawlogs harvested from multiple-use public native forest for 2016-17 to 2020-21 was 119 thousand cubic metres, which was 13% below the calculated sustainable yield for the same period (Figure 2.1c.i-4).

The average annual sustainable yield of high-quality sawlogs from multiple-use public native forests in Tasmania has reduced by 61% since 2001-02 as a result of the reduction in net harvestable area between 2001-02 and 2020-21 (Figure 2.1c.i-4).

The minimum annual high-quality sawlog volume was set from the 2017 review of sustainable high-quality sawlog supply levels from Permanent Timber Production Zone (PTPZ) land undertaken by Sustainable Timber Tasmania. Reviews of sustainable high-quality sawlog supply levels are required by the Tasmanian Regional Forest Agreement. These wood supply forecasts inform a legislated minimum annual volume to be made available to industry, as detailed in Tasmania’s Forest Management Act 2013. The 2017 sustainable yield review confirmed that this legislated high-quality sawlog volume was available on an ongoing basis from a mix of multiple-use public native forest and public hardwood plantations (STT 2017). Supplementation with high-quality sawlogs from public-owned hardwood plantations has formed part of the sustainable wood supply strategy since 1997.

After the signing of the Tasmanian Regional Forest Agreement in 1997, a non-declining yield for native forest sawlogs of 225 thousand cubic metres was forecast to be maintained up to and beyond 2020 (Forestry Tasmania 2002). Following the 2005 Tasmanian Community Forest Agreement, this sustainable yield was reduced to 145 thousand cubic metres after 2023 (Forestry Tasmania 2007). Subsequently, following the 2013 Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement process, a further reduction in net harvestable area (Indicator 2.1a) led to the legislated yield being reduced to 137 thousand cubic metres.

The outcomes of the 2013 Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement process were incorporated into the Sustainable Timber Tasmania 2017 and 2022 resource reviews (including the proposed Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area extension). The 2022 resource review indicated the level of high-quality sawlog supply from multiple-use public native forest was forecast to be 130 thousand cubic metres to 2027, reducing to 58 thousand cubic metres to 2045, and then increasing slightly to about 68 thousand cubic metres for the remainder of the 90-year modelling period (STT 2022). Significant quantities of high-quality sawlogs from public hardwood plantations were included in the forecast to compensate for the decrease in native forest sawlogs after 2027. An area of 356 thousand hectares of native forest allocated as Future Potential Production Forest (FPPF) land under the Forestry (Rebuilding the Forest Industry) Act 2014 was not included in the 2017 supply estimates.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1c.i-4.

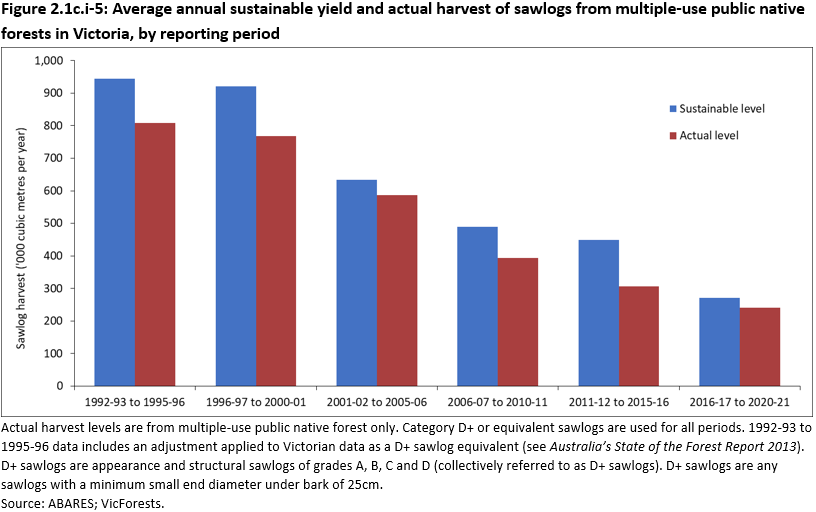

The actual average annual high-quality sawlog harvest was 241 thousand cubic metres from multiple-use public native forests in Victoria for the period 2016-17 to 2020-21. This was 11% below the calculated sustainable yield for the same period (Figure 2.1c.i-5).

Since the period 1992-93 to 1995-96, sustainable yields and actual harvest volumes in Victoria have both declined, with harvest volumes remaining below the calculated sustainable yields. The sustainable yield has reduced from 945 thousand cubic metres to 271 thousand cubic metres since 1992 93 (a 71% reduction). Three intense, broad-scale bushfire events in eastern Victoria (2002-03, 2006-07, 2009) significantly contributed to decreases in sustainable yield during the corresponding reporting periods.

Periodic wood supply forecasts have been carried out for eastern Victoria to account for natural disturbance events such as fire, and to incorporate updated resource information Resource outlooks have been published by VicForests (VicForests 2011; 2013; 2014; 2017). Forest Solutions (2013) reviewed the expected wood yields from multiple-use public native forests in Western Victoria.

The calculated sustainable yield reported for the 2016-17 to 2020-21 period reduced by 40% from the preceding period due to:

- restrictions on harvesting in mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans) forests imposed following concerns for Leadbeater’s possum (Gymnobelideus leadbeateri) and other threatened species

- exclusion of all pre-1900 alpine ash and mountain ash ‘old growth’ stands

- exclusion of approximately 11 thousand hectares of net harvestable area assumed to be unavailable due to community and/or market concerns

- general updates to the forest zoning base by the regulator (VicForests 2017).

Following the 2019-20 ‘Black Summer’ bushfires, the Victorian Government carried out a Harvest Level Review, as required under the Victorian Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs), to assess the impacts of the bushfires on harvest volumes in eastern Victoria (DJPR 2021). In the Victorian RFAs, ‘harvest level’ is defined as the volume of timber resources that can be harvested from native forests in RFA regions in any financial year, consistent with Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management principles, until the native forest harvesting end date. The review estimated reductions in the total operable inventory of 9% for D+ sawlog volumes in ash forest and 13% in D+ sawlog volumes from mixed-species forest (D+ sawlogs are high-quality sawlog grades A, B, C and D). The harvest level review concluded that post-fire standing high-quality sawlog volumes remained adequate to maintain Victoria’s supply commitments until the 2030 native forest harvesting end date.

In 2019, the Victorian Government announced that wood harvesting on multiple-use public native forest would be phased out by 2030. In 2023, the Victorian Government announced the end date would be brought forward to 01 January 2024. The ending of wood harvesting on multiple-use public native forest in Victoria significantly impacts future national sustainable high-quality sawlog yields, as described in Indicator 2.1c.iii.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1c.i-5.

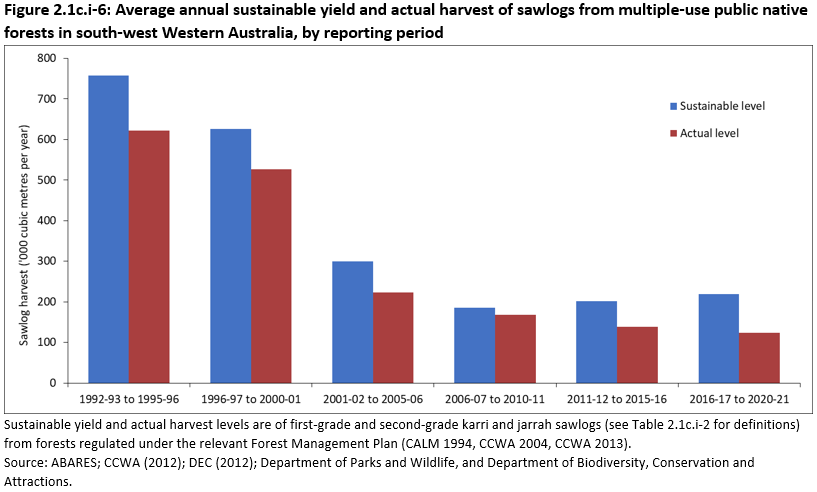

For the period 2016-17 to 2020-21, the calculated sustainable yield of high-quality sawlogs in Western Australia was 219 thousand cubic metres, while the actual average annual volume harvested was 124 thousand cubic metres, which was 57% of the calculated sustainable yield for the same period (Figure 2.1c.i-6).

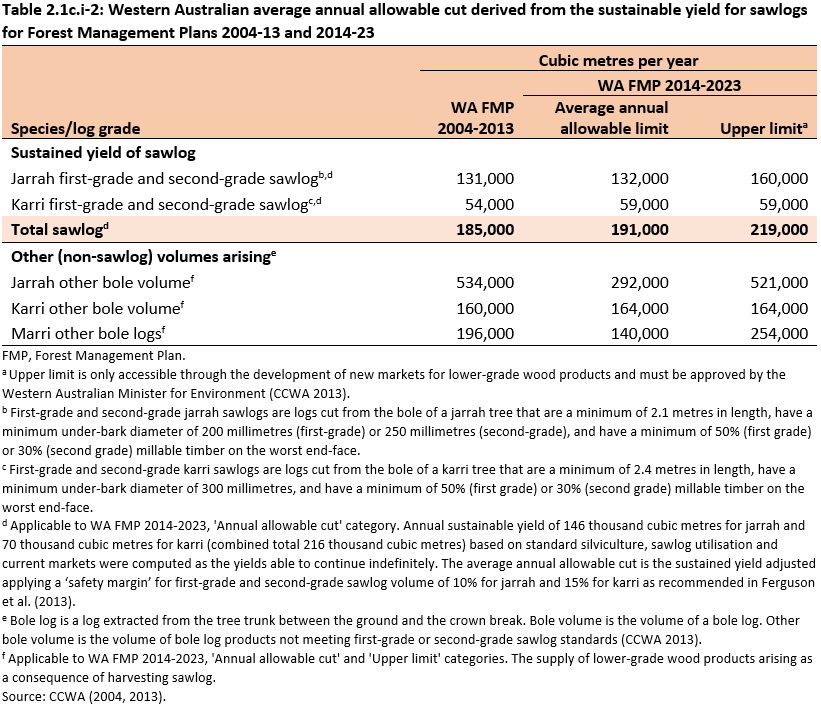

Independent reviews of sustainable yield from multiple-use public native forests have supported the development of two 10-year forest management plans for south-west Western Australia (CCWA 2004; CCWA 2013). The forest management plans require forecasts of the sustainable yield for high-quality jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) and karri (E. diversicolor) sawlogs and incorporate the allowable harvest for these species. Under each Forest Management Plan the annual harvest can exceed the average annual allowable cut in some years but must not, over the ten-year period of the plan, exceed the cumulative total allowable cut. Key performance indicators associated with each plan set the maximum amount by which the annual cut can exceed the average allowable cut: 10% for the Forest Management Plan 2004-2013; a progressive scaling down was introduced for the Forest Management Plan 2014-2023 of 10% at year 3, 5% at year 6, and 3% at year 9.

In addition, the Forest Management Plan 2014-2023 specified an average annual allowable cut of sawlogs and other bole volume for jarrah, karri and marri (Corymbia calophylla) (Table 2.1c.i-2), and an upper limit for these should market opportunities arise. Setting the allowable cut below the sustainable yield allows for impacts of natural events such as bushfire, drought or disease. However, the allowable cut assumed current industry technologies, practices and markets for lower-grade products, whereas the upper limit provided for the potential expansion of silvicultural thinning programs in young regrowth and the development of markets for lower-grade products. The setting of an allowable cut below the sustainable yield allows for impacts of natural events such as bushfire, drought or disease. The average annual allowable cut of 191 thousand cubic metres of jarrah and karri sawlogs is 13% below the combined upper limit forecast sustainable sawlog yield of 219 thousand cubic metres (Table 2.1c.i-2).

The calculated sustainable yield and actual harvest yield from multiple-use public native forests in Western Australia declined significantly following the implementation of the Western Australian Regional Forest Agreement and again after the adoption of the Forest Management Plan 2004-2013 (CCWA 2004). Since 2006-07, the calculated sustainable yield has increased by 18%, while actual sawlog harvest volumes have decreased by 27%.

In 2021, the Western Australian Government announced that large-scale commercial wood harvesting would end on multiple-use public native forest from 01 January 2024. The ending of commercial wood harvesting on multiple-use public native forest in Western Australia significantly impacts future national sustainable high-quality sawlog yields, as shown in Indicator 2.1c.iii.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1c.i-6.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 2.1c.i-2.

Sustainable yield estimates of high-quality sawlogs from multiple-use public native forests in New South Wales and Tasmania include supplementation with sawlogs of similar quality from public hardwood plantations. The supplementary component of sustainable yield estimates is based on projected yields of high-quality sawlogs from these plantations.

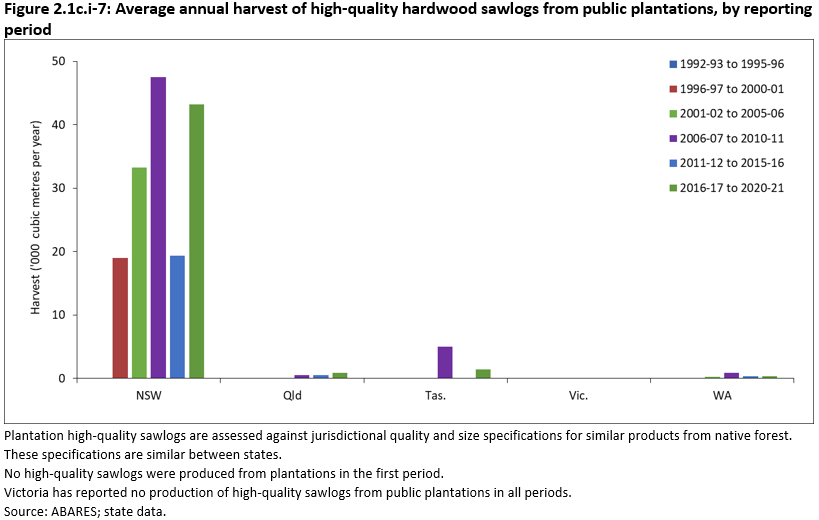

To date the annual plantation hardwood high-quality sawlog harvests have been relatively small for all states except New South Wales (Figure 2.1c.i-7). However, the supplementary quantities of high-quality sawlogs are forecast to increase significantly in New South Wales after 2024 and in Tasmania after 2026 (FCNSW 2020; STT 2022). In New South Wales, high-quality sawlogs (primarily Eucalyptus pilularis, E. grandis and E. dunnii) have been harvested from public hardwood plantations in the north-eastern part of the state since 1997-98.

Following the implementation of the South East Queensland Forests Agreement (SEQFA) in 1999, the Queensland Government commenced a hardwood plantation planting program to provide an alternative hardwood sawlog resource to industry. However, the program was eventually abandoned due to a combination of issues (such as marginal site quality, climate variability and pest and disease) that led to generally poor plantation performance.

The individual years 2019-20 and 2020-21 saw large increases in volumes of high-quality sawlog harvested from New South Wales public hardwood plantations (73 thousand cubic metres and 79 thousand cubic metres, respectively), compared to the average annual volumes harvested during the 2011-12 to 2015-16 period (19 thousand cubic metres). This compensated for some of the shortfall of high-quality sawlog volumes harvested from New South Wales multiple-use public native forest in the years after the 2019-20 bushfires.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1c.i-7.

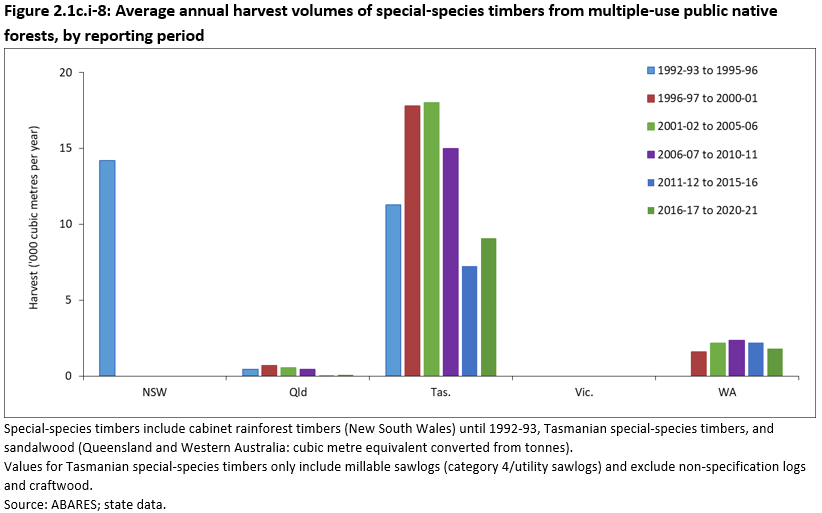

The average annual volumes of special-species timbers harvested from public native forests have varied widely between years and between states since 1992-93 (Figure 2.1c.i-8). Tasmania has been the main source of special species timbers nationally since the Australia’s State of the Forests Report series began.

Native sandalwood is included as a special-species timber in Queensland and Western Australia. Harvesting rainforest timbers (typically higher-value species used in cabinet making and other speciality products) ceased in New South Wales after 1992-93. Special-species in Tasmania are defined in legislation as:

- blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon)

- silver wattle (A. dealbata)

- myrtle (Nothofagus cunninghamii)

- sassafras (Atherosperma moschatum)

- celery-top pine (Phyllocladus aspleniifolius)

- huon pine (Lagarostrobos franklinii).

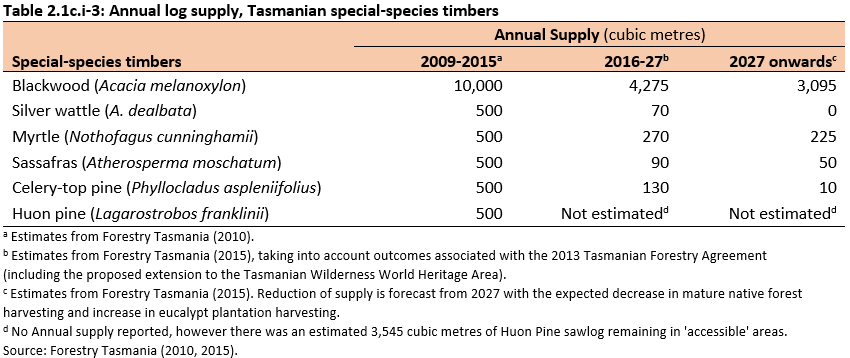

Tasmanian special-species timbers make an important contribution to the Tasmanian economy (DSG 2017). A strategy to ensure the continued long-term production of Tasmanian special-species timbers from public native forests was implemented in 2010 (Forestry Tasmania 2010). This was based on sustainable yield estimates for each of the key special-species (Table 2.1c.i-3). After the reduction in the public native forest production estate resulting from the 2013 Tasmanian Forest Agreement, the sustainable supply of Tasmanian special-species timbers was reviewed and supply levels recalculated for Permanent Timber Production Zone (PTPZ) land (Forestry Tasmania 2015). The updated supply estimates are provided in Table 2.1c.i-3. Forestry Tasmania (2017) and the Tasmanian Special Species Management Plan (DSG 2017) presented estimates of special-species timber volumes in other land management categories (including Future Potential Production Forest) and tenures, but these are not included in the supply estimates provided in Table 2.1c.i-3.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1c.i-8.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 2.1c.i-3.

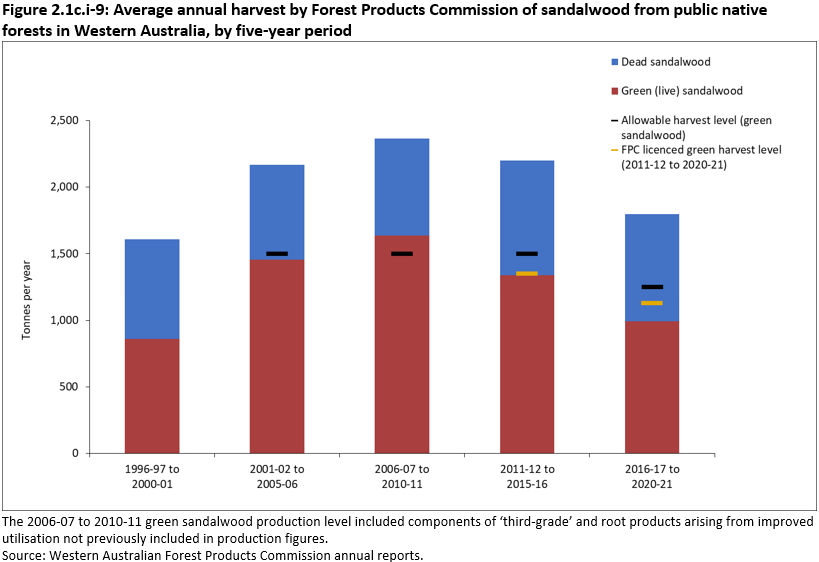

In Western Australia, harvest of Australian sandalwood (Santalum spicatum) comprise high-grade and low-grade green (live) sandalwood, sandalwood root and bark, and dead sandalwood under licence from public and private lands. The total annual allowable harvest level of green sandalwood is set by the Sandalwood (Limitation of Removal of Sandalwood) Order (No. 2) 2015 (DAFF 2022). During the period 2016-17 to 2020-21, the total allowable harvest level of green sandalwood was up to 1,250 tonnes per annum, of which the Forest Products Commission (FPC) was licenced to remove 1,125 tonnes per annum. This quota applies until 2026, when sandalwood plantations are expected to begin to contribute significantly to the supply of sandalwood (FPC 2016; FPC 2021).

Figure 2.1c.i-9 shows the average annual sandalwood harvest by FPC from Western Australian public native forest by five-year periods. Notably, green (live) sandalwood trees produce more oil than dead trees and consequently have higher commercial value.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1c.i-9.

Brack C (2017). FRAMES Review, Australian National University, Canberra.

Brack C and Vanclay J (2011). Independent review of Forestry Tasmania Sustainable Yield Systems.

CALM (Department of Conservation and Land Management) (1994). Forest Management Plan 1994–2003, Department of Conservation and Land Management, Perth.

CCWA (Conservation Commission of Western Australia) (2004). Forest Management Plan 2004–2013, Conservation Commission of Western Australia, Perth.

CCWA (Conservation Commission of Western Australia) (2012). Forest Management Plan 2004–2013 End-of-term Audit of Performance Report, Conservation Commission of Western Australia, Perth.

CCWA (Conservation Commission of Western Australia) (2013). Forest Management Plan 2014–2023, Conservation Commission of Western Australia, Perth.

DAFF (Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry) (2022). State Specific Guideline for Western Australia, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Canberra.

Davey S (2018). Regional Forest Agreements: origins, development and contributions, Australian Forestry 81:64-88.

Davidson J, Davey S, Singh S, Parsons M, Stokes B and Gerrand A (2008). The Changing Face of Australia’s Forests, Bureau of Rural Sciences, Canberra.

DEC (Department of Environment and Conservation) (2012). Sustained yield information sheet series, Department of Environment and Conservation, Perth.

DJPR (Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions) (2021). Harvest Level in Victorian Regional Forest Agreement regions, Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions, Melbourne.

DSG (Tasmanian Department of State Growth) (2017). Tasmanian Special Species Management Plan. Department of State Growth, Hobart.

FCNSW (Forestry Corporation of NSW) (2020). 2019-20 Wildfires: NSW Coastal Hardwood Forests Sustainable Yield Review, Forestry Corporation of NSW, Sydney.

Ferguson I, Dell B and Vanclay J (2013). Calculating the sustained yield for the south-west native forests of Western Australia, Report for the Conservation Commission and the Department of Environment and Conservation of WA by the Independent Expert Panel. Conservation Commission of Western Australia, Perth.

Forest Solutions (2013). Review of Commercial Forestry Management in Western Victoria: Timber Resources, Harvest Levels, Silviculture, and Systems and Processes. Department of Environment and Primary Industries, Melbourne.

Forestry Tasmania (2002). Sustainable High Quality Eucalypt Sawlog Supply from Tasmanian State Forest – Review No. 2, Planning Branch, Forestry Tasmania, Hobart.

Forestry Tasmania (2007). Sustainable High Quality Eucalypt Sawlog Supply from Tasmanian State Forest – Review No. 3, Planning Branch, Forestry Tasmania, Hobart.

Forestry Tasmania (2010). Special Timbers Strategy, Forestry Tasmania, Hobart.

Forestry Tasmania (2013). A Review of the Sustainable Sawlog Supply from the Blackwood Management Zone, Forestry Tasmania, Hobart.

Forestry Tasmania (2015). Special Timbers Resource Assessment on Permanent Timber Production Zone Land. A report to Department of State Growth and Ministerial Advisory Council Special Timbers Subcommittee, Forestry Tasmania, Hobart.

Forestry Tasmania (2017). Special Timbers Resource Assessment on Permanent Timber Production Zone Land, Future Potential Production Forest Land, Regional Reserves and Conservation Areas. A report to Department of State Growth and Ministerial Advisory Council Special Timbers Subcommittee, Forestry Tasmania, Hobart.

Forests NSW (2010). Forests NSW yield estimates for native forest regions, Forests NSW, Pennant Hills.

FPA (Forest Practices Authority) (2022). State of the forests Tasmania 2022 data report, Forest Practices Authority, Hobart.

FPC (Forest Products Commission) (2016). Forest Products Commission Annual Report 2015-16, Forest Products Commission, Perth.

FPC (Forest Products Commission) (2021). Sandalwood Management Plan, Forest Products Commission, Perth.

Jacobsen R, Davey, SM, Read SM 2020, Regional forest agreements: compilation of reservation and resource availability outcomes, ABARES Technical report 20.11, Canberra, December. CC BY 4.0. doi.org/10.25814/n975-d613

NSW DPI (New South Wales Department of Primary Industries) (2018). Sustainable Yield in New South Wales Regional Forest Agreement regions, DPI, Sydney.

Queensland Government (1998). Background to Assessment of Queensland’s Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management Systems and Processes – Description Report, Department of Natural Resources – Resource Management, Department of Communications, Information, Local Government and Planning, Department of Primary Industries – Forestry and Department of Environment and Heritage, Brisbane.

Queensland Government (2019). Palaszczuk Government takes action to support timber industry jobs. Queensland Government, Brisbane. Accessed May 2024. statements.qld.gov.au/statements/88797

STT (Sustainable Timber Tasmania) (2017). Sustainable high quality eucalypt sawlog supply from Tasmania’s Permanent Timber Production Zone Land - Review No. 5, Sustainable Timber Tasmania, Hobart.

STT (Sustainable Timber Tasmania) (2022). Sustainable high quality eucalypt sawlog supply from Tasmania’s Permanent Timber Production Zone Land - Review No. 6, Sustainable Timber Tasmania, Hobart.

VicForests (2011). VicForests 2011 Resource Outlook, VicForests. Melbourne.

VicForests (2013). VicForests 2013 Resource Outlook, VicForests, Melbourne.

VicForests (2014). VicForests 2014 Resource Outlook, VicForests, Melbourne.

VicForests (2017). VicForests 2016-17 Resource Outlook, VicForests, Melbourne.