This indicator identifies the scale and impact on forest health of a variety of processes and agents, both natural and human-induced. Through the regular collection of this information, significant changes to the health and vitality of forest ecosystems can be monitored and measured.

This is the Key information for Indicator 3.1a, published October 2024.

- The five main introduced vertebrate pests that damage forests are widespread in one or more states and territories: rabbit, feral pig, feral deer, feral goat and feral horse.

- The most damaging insect species in eucalypt plantations are locally native species, except in Western Australia where native Gonipterus spp. have spread from eastern Australia.

- Insects damaging sandalwood (Santalum spp.) plantations are reported for the first time.

- The area proportion of softwood (Pinus spp.) plantations suffering damage from insect pests is low.

- Two introduced pathogens, Phytophthora cinnamomi and Austropuccinia psidii (myrtle rust), are established in multiple-use public native forests and in native forests in nature conservation reserves in several states and continue to cause damage. Both pathogens are subject to active management.

- Weeds are widespread through Australia’s forests, with prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) the most widespread and occurring in all states and territories.

- Forests in the Australian Capital Territory and New South Wales have the highest overall proportion of forest area affected by weeds, and Tasmania the lowest.

- Record-breaking heatwave events caused mass tree deaths in large areas of forest, and mass deaths of Vulnerable and Endangered flying foxes, between 2017 and 2021 which was Australia’s hottest five-year period in the past 100 years.

National arrangements for forest biosecurity continued to be strengthened over the period 2016-21, with the introduction of a National Forest Pest Surveillance Program. Key initiatives of this program include the appointment of a Chief Environmental Biosecurity Officer, and a National Priority List of Exotic Environmental Pests, Weeds and Diseases which was released in 2021 to support strengthening of environmental biosecurity by identifying significant threats and developing a national approach to addressing them. In addition, a National Forest Biosecurity Coordinator was appointed to coordinate and administer activities for the national program under the guidance of a National Forest Biosecurity Steering Group representing major stakeholders, and active surveillance of high-risk sites by technical experts.

National action plans now underpin management of the most damaging introduced vertebrate predators and herbivores, each of which are established in most Australian states and territories. National coordinators have been appointed for most of the key feral vertebrate pests to facilitate consistent, best-practice landscape-scale management across properties.

Australia’s weed policy was updated in 2017 to build on previous work with the Weeds of National Significance and provide better delivery of management actions at the landscape level. This enabled many organisations and groups to make rapid, targeted responses after the Black Summer bushfires in 2019-20, when bushfire recovery funding from the Australian Government assisted the treatment of weeds across 40 thousand hectares of land (DCCEEW 2022). The National Priority List of Exotic Environmental Pests, Weeds and Diseases includes 20 potentially invasive weed species in addition to the 24 common existing weeds reported here for forests (Tables 3.1a-4a, b, c).

Systems and procedures for detecting and controlling invasive weeds at an early stage of establishment have been strengthened. Regular surveillance and mapping underpin the detection and management of early weed invasions. For example, since 2017, 19 weed species have been classed as early invaders in the Central Highlands of Victoria, and are the focus of eradication campaigns. All known individuals of four of those 19 weed species have since been eradicated. In Queensland, 37 of 59 high-risk weed species have either been eradicated or are on track for eradication.

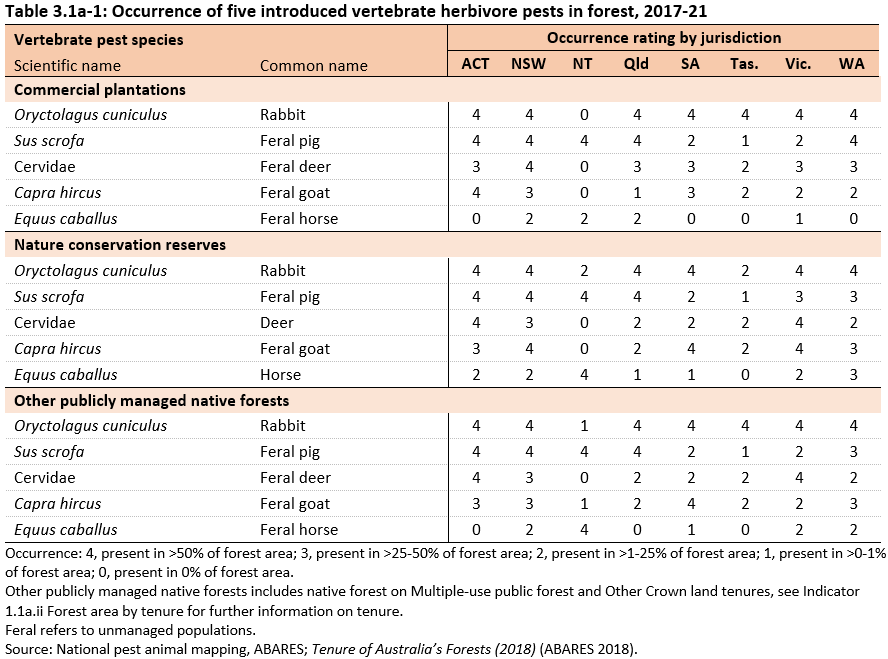

Five main introduced vertebrate herbivore pest species (rabbit, feral pig, feral deer, feral goat and feral horse) are known to be widespread in commercial plantations and publicly managed forests in one or more states and territories (Table 3.1a-1). All cause damage to forests, particularly to young regenerating forests and plantations. Use of the term feral refers to unmanaged populations.

Of the five introduced herbivores identified as widespread pests in forests, rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) and feral pigs (Sus scrofa) are identified as the most widespread across the commercial plantations, forest in nature conservation reserves and other publicly managed native forest (Table 3.1a-1). Feral goats (Capra hircus) have been detected in forests in all states and territories, but not in commercial plantations or nature conservation reserves of the Northern Territory. Feral deer (Cervidae species) have been detected in forests in all states and territories except for the Northern Territory. Feral horses (Equus caballus) have been detected in forests in all states and territories except for Tasmania.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 3.1a-1.

During the period from 2017 to 2021:

- rabbit populations declined due to new strains of the rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (Calicivirus)

- feral deer populations increased in Tasmania, Victoria and New South Wales

- feral horse populations increased sharply in alpine areas of Victoria and New South Wales, and are becoming an increasing road issue in South East Queensland coastal plantations.

After the Black Summer fires in 2019-20, there was a sharp increase in control operations against feral animals in New South Wales and Victoria to protect native forest regeneration.

Native vertebrate species continue to impact forests due to:

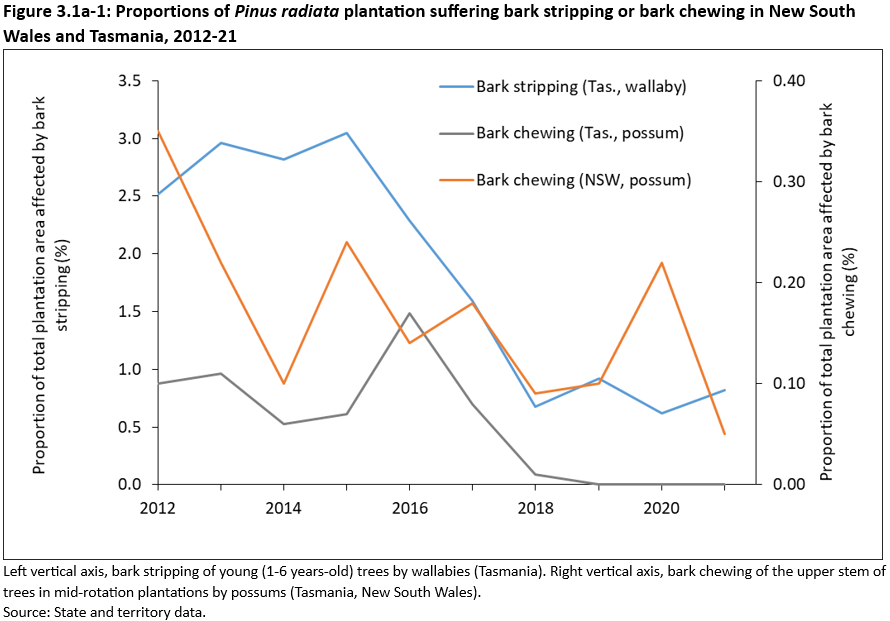

- browsing by wallabies, possums and pademelons which damage young plantations and regenerating native forests in temperate south-eastern Australia

- bark stripping and chewing of trees by native herbivores in young Pinus radiata plantations which is an ongoing problem in Tasmania and New South Wales, although the impact by Bennett's wallaby (Notamacropus rufogriseus) and brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) on P. radiata plantations declined in Tasmania during the period 2017-21 and the area of plantation suffering bark chewing by brushtail possum in New South Wales remained at levels comparable with that recorded in the previous five-year period (Figure 3.1a-1).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 3.1a-1.

Insect damage in commercial and sandalwood (Santalum spp.) plantations

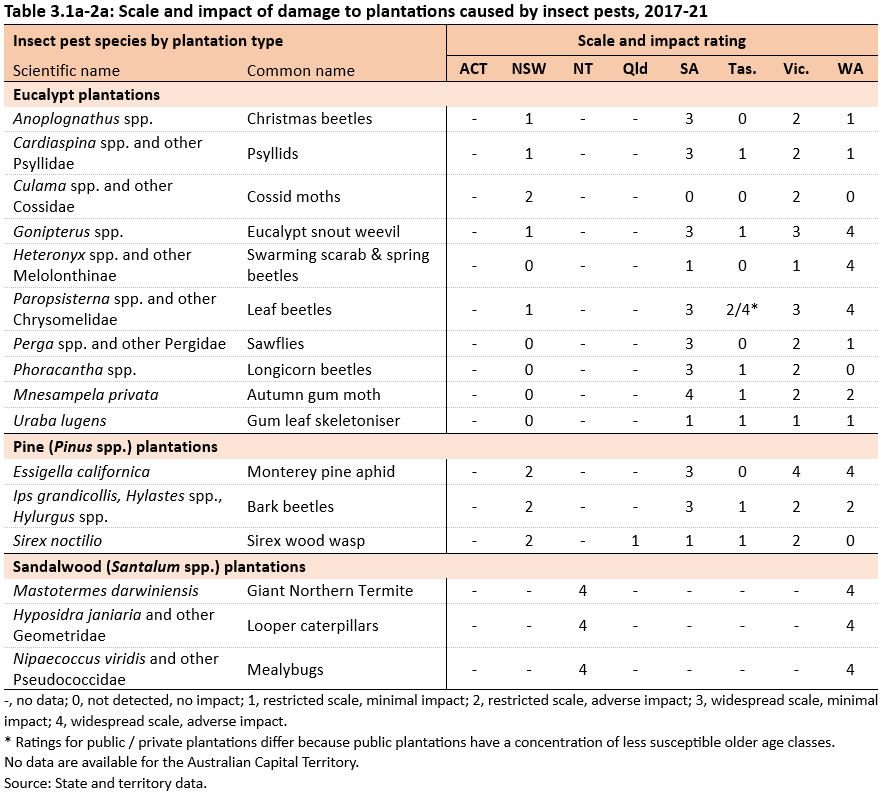

The most damaging insect species in eucalypt plantations are locally native species, except for Gonipterus species that have spread from eastern Australian to become established in Western Australia (Table 3.1a-2a). Control operations against defoliating insects in eucalypt plantations were undertaken in only Tasmania and Western Australia.

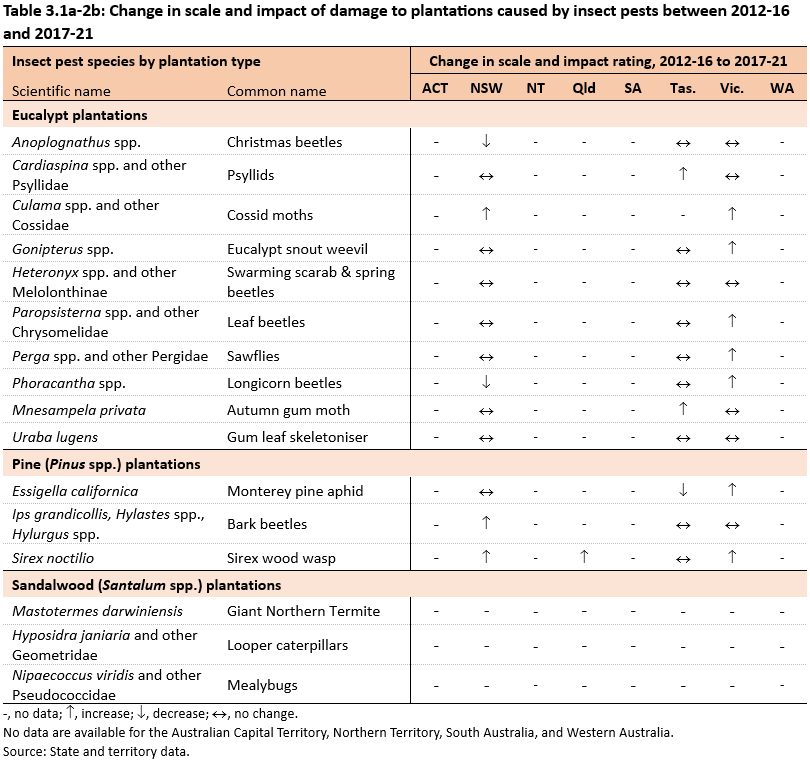

The scale and impact of plantation insect pests in New South Wales, Tasmania and Victoria in 2017-21 were mostly unchanged from 2012-16 (23 of the 38 jurisdiction-pest combinations for which scale and impact data are available in both periods, Table 3.1a-2b). In instances where change in scale and impact did occur between these periods, the change was mostly an increase (12 of 38 instances) and more rarely a decrease (3 of 38 instances). Data on change in scale and impact between 2012-16 and 2017-21 for insects damaging sandalwood (Santalum spp.) plantations are not available because this is first time data on insects damaging sandalwood have been reported in Indicator 3.1a. A number of species remained relatively localised (restricted in scale), but their impact increased in these areas (for example, psyllids in Tasmania and sawflies in Victoria).

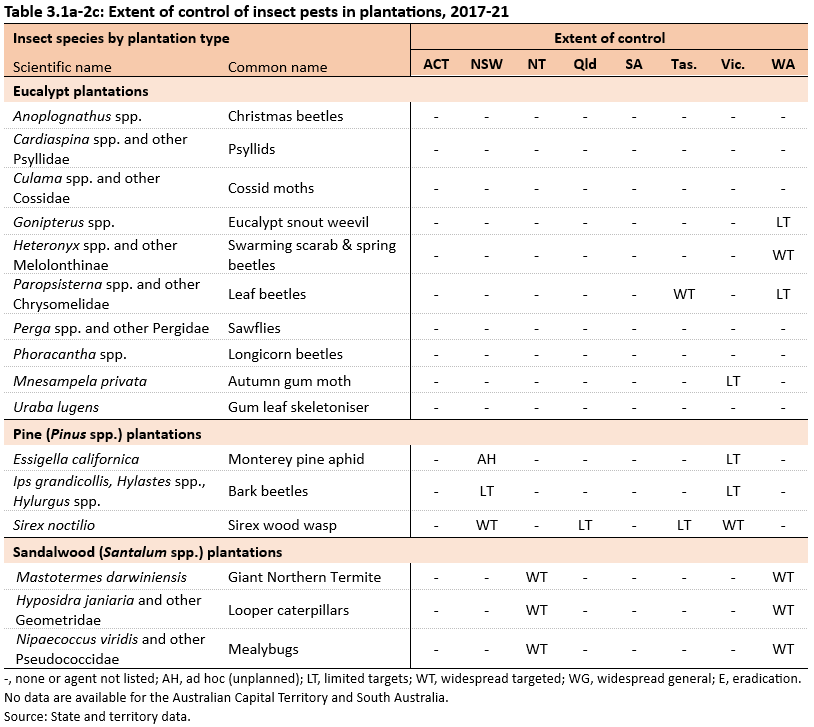

Data on the major insect pests causing damage in both commercial and sandalwood (Santalum spp.) plantations include:

- scale and impact of damage to plantations caused by insect pests in 2017-21 (Table 3.1a-2a)

- change in scale and impact of damage to plantations caused by insect pests between 2012-16 and 2017-21 (Table 3.1a-2b)

- extent of control of insect pests in plantations in 2017-21 (Table 3.1a-2c).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 3.1a-2a.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 3.1a-2b.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 3.1a-2c.

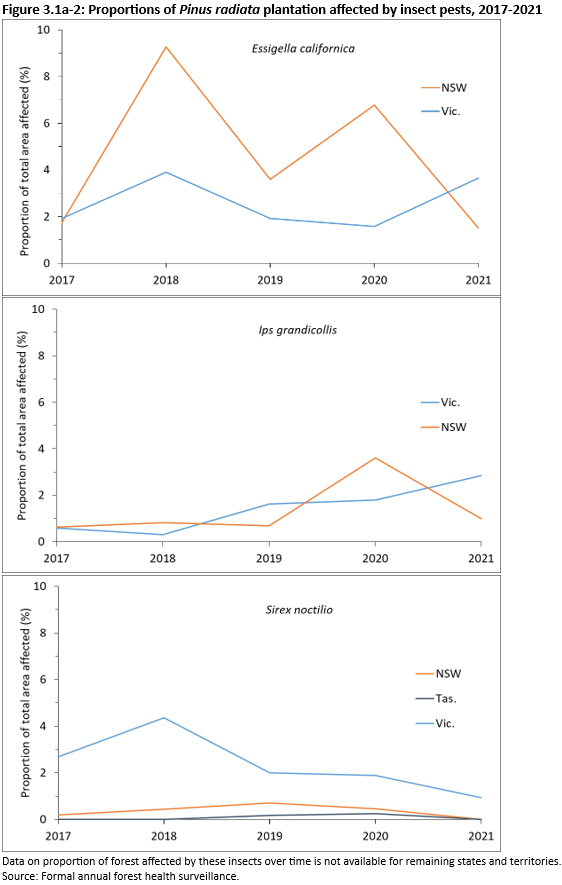

The area proportion of pine (Pinus spp.) plantations suffering damage from the three main groups of introduced insect pests (Ips grandicollis, Essigella californica and sirex wood wasp—Sirex noctilio) was generally low, although there were slight increases in E. californica damage in response to drought and in I. grandicollis damage in response to fire (Figure 3.1a-2), while in Tasmania, E. californica is only detected periodically in low populations in the south of the state, and I. grandicollis has not established. There was a slow movement of sirex wood wasp across the New South Wales border into Queensland, and a transient increase in the area of Victorian pine plantations affected by sirex wood wasp in 2018 (Figure 3.1a-2), associated with the replacement of the main biological control agent (the Kamona strain of the nematode Deladenus siricidicola) with another established strain of that species.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 3.1a-2.

Insect damage in native forests

Most insects causing damage in native forests are native species and are not subject to active monitoring or management programs, except in the case of rare or unusual damaging outbreaks. As such, quantitative data on the scale and impact of insect pests in multiple-use native forests or forests in nature conservation reserves are not available.

Attack by a native longicorn beetle, Phoracantha mastersi, was associated with dying snow gum (Eucalyptus pauciflora subsp. niphophila) trees in alpine areas across the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales and Victoria. Drought conditions coupled with warming temperatures over the last decade, which favour the beetle, were implicated in the increased beetle activity.

Biosecurity responses

The giant pine scale (Marchalina ornicate), which in heavy infestations can defoliate and kill Pinus species, remains in the Melbourne area after an unsuccessful eradication campaign in 2014, and is now the focus of research to support a transition to management. The scale was also detected in metropolitan Adelaide in 2014 and again in 2018. A priority of South Australia’s management of the pest is to protect forest industries and amenity tree plantings through surveillance and the urgent removal of infested trees. This is currently the best-known option for eliminating giant pine scale and preventing its spread in South Australia.

A national biosecurity response led by Western Australia was triggered when an exotic wood-boring beetle native to south-east Asia—the polyphagous shot-hole borer (Euwallacea ornicates)—was detected in Fremantle in winter 2021. The detection was declared an Emergency Plant Pest due to the threat it poses for trees in native and urban forests, as well as horticulture tree crops. Quarantine restrictions have been implemented with removal of infested trees and gathering information necessary to determine the feasibility of eradication is underway. As of October 2024, containment measures were ongoing.

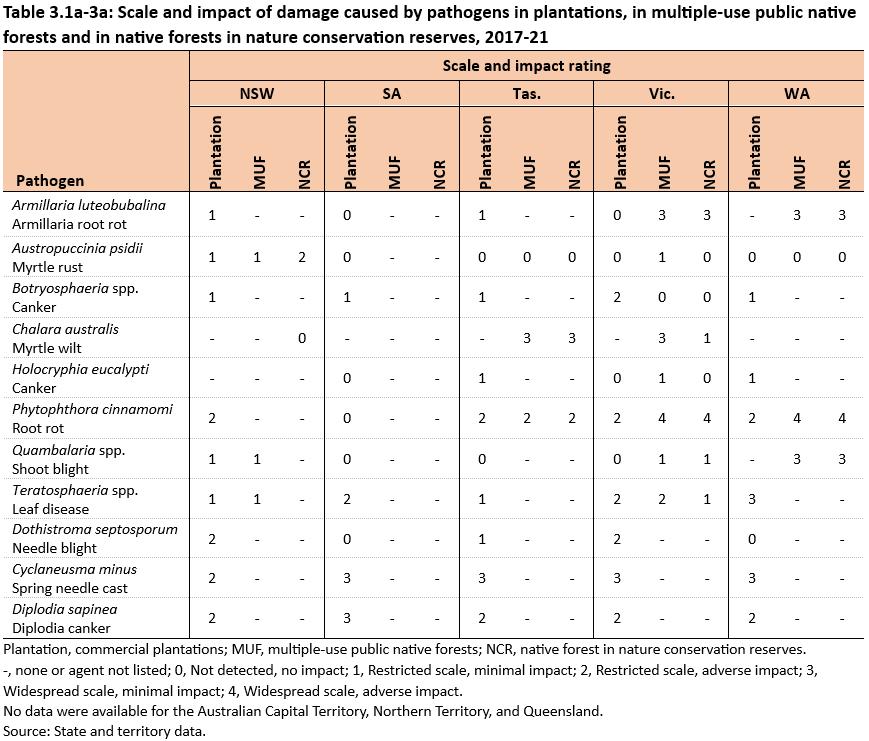

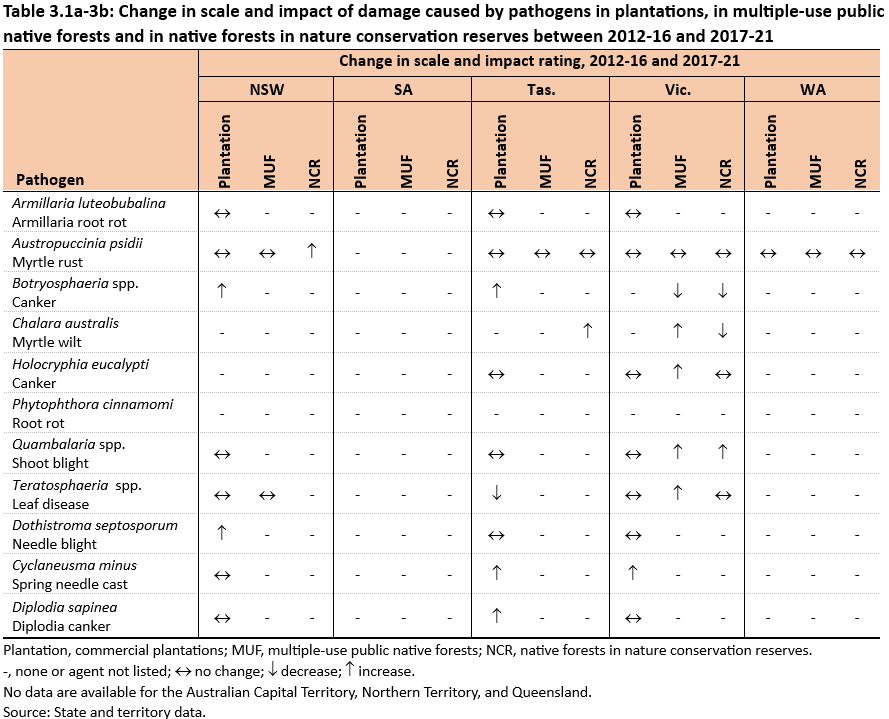

Pathogens such as fungi, viruses, bacteria and worms, continue to impact native forests and commercial plantations, especially via the roots and leaves or needles of trees which can affect a tree’s nutrient transport system. Of the pathogens for which data on scale (extent), impact and control measures are available, the following were observed:

- in 5 instances pathogens declined in scale and impact

- in 29 instances pathogens had no change in their scale and impact

- in 22 instances pathogens increased in scale and impact.

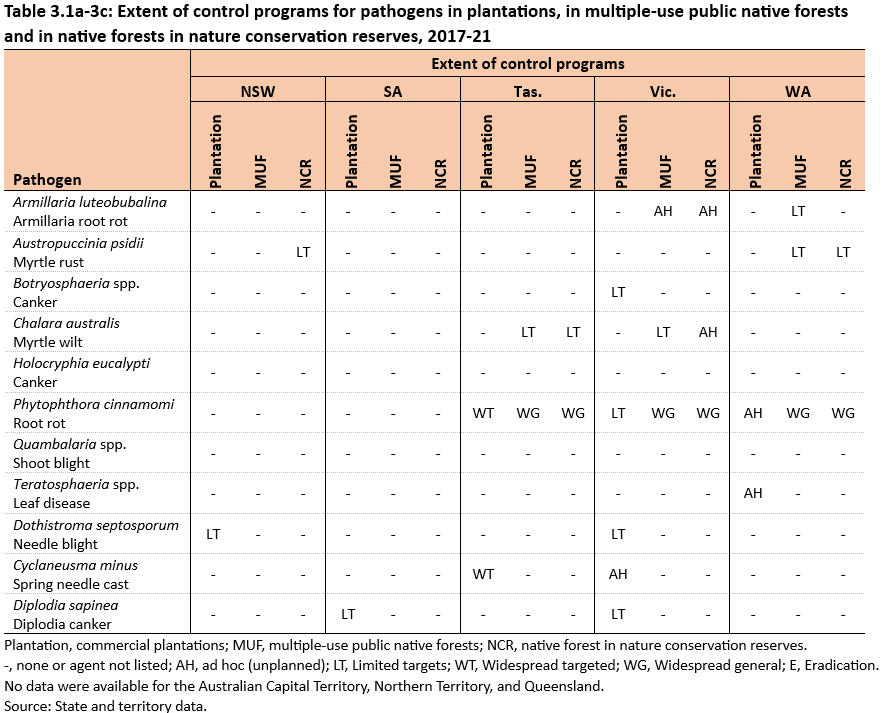

Data on the major pathogens causing damage in commercial plantations, in multiple-use public native forests and in native forests in nature conservation reserves include:

- scale and impact in the period 2017-21 (Table 3.1a-3a)

- change in scale and impact of damage between 2012-16 and 2017-21 (Table 3.1a-3b) and

- extent of control programs for pathogens in the period 2017-21 (Table 3.1a-3c).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 3.1a-3a.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 3.1a-3b.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 3.1a-3c.

Pathogen damage in native forests

Two introduced pathogens, Phytophthora dieback (Phytophthora cinnamomi) and myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii), are established and cause damage in multiple-use public native forests and native forests in nature conservation reserves in several states, and are subject to active management.

There are two Phytophthora species known to impact forests in Australia. P. cinnamomi is the most damaging species, particularly in south-west Western Australia where 15% of the forests are infested. The more localised P. multivora was associated with dieback and mortality of bunya pine (Araucaria bidwillii) in the Bunya Mountains National Park in Queensland. Damage by P. multivora intensified between 2017 and 2020 when drought conditions developed after a period of higher-than-normal rainfall, adding water stress to disease stressed plants.

Myrtle rust continues to cause severe damage to Myrtaceae plant species in subtropical wet sclerophyll and rainforest communities in New South Wales and Queensland.

- Three species of Myrtaceae (Rhodamnia rubescens, Rhodomyrtus psidioides and Lenwebbia sp. “Main Range”) have been listed as Critically Endangered under both national and state legislation because their wild populations have declined largely due to myrtle rust; conservation measures in areas free of myrtle rust are underway.

- A further sixteen Myrtaceae species are at risk of extinction in the wild.

Armillaria luteobubalina and Chalara australis are the only two native pathogens that cause damage sufficient to warrant periodic management in multiple-use native forests and native forests in nature conservation reserves. Armillaria luteobubalina causes root rot in eucalypt species, and Chalara australis causes mortality in myrtle beech tree (Nothofagus cunninghamii).

Pathogen damage in commercial plantations

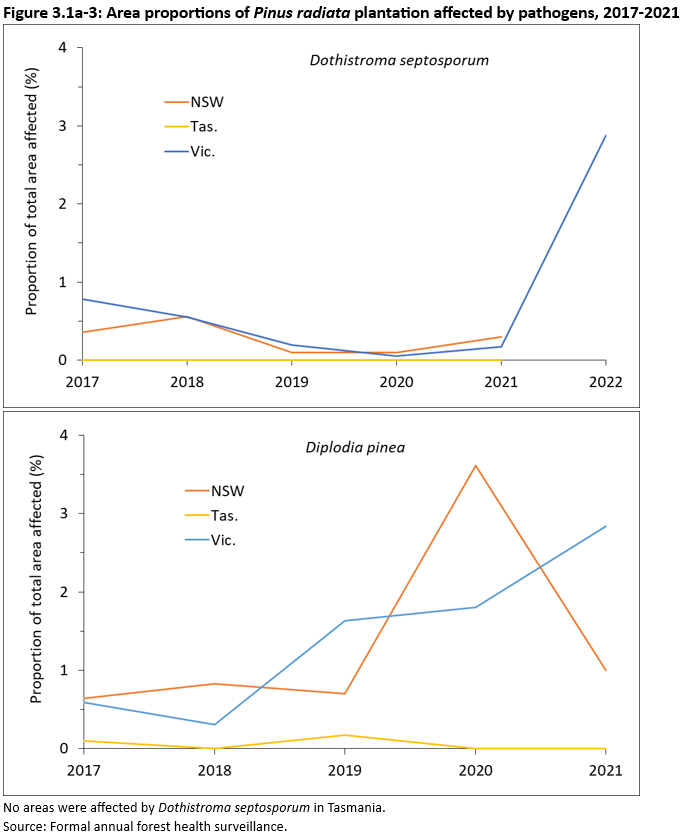

The needle-infecting pathogen Dothistroma septosporum, which affects Pinus radiata, was constrained in the dry conditions occurring in much of Australia between 2017 and 2020, resulting in a low proportion of P. radiata plantations experiencing defoliation (Figure 3.1a-3). However, above-average rainfall in 2021 led to a sharp increase in defoliation due to this pathogen in Victoria.

In contrast, the dry conditions between 2017 and 2020 favoured Diplodia pinea, resulting in a sharp increase in infection (known as ‘top-death’) of P. radiata plantations in Victoria and New South Wales (Figure 3.1a-3). The portion of area impacted subsequently reduced because of the wet seasons that followed in 2021.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 3.1a-3.

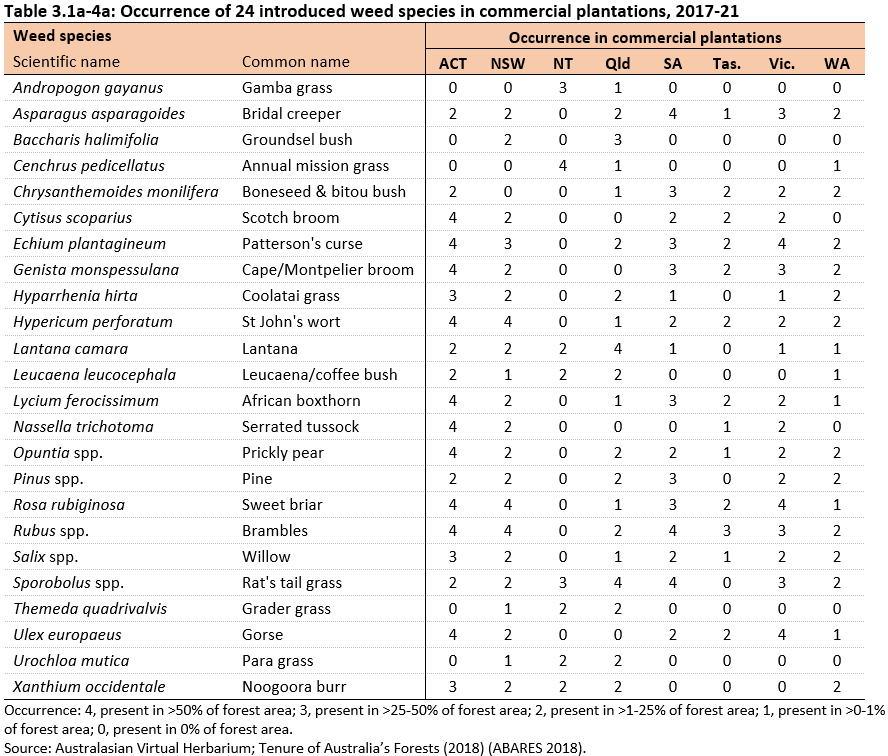

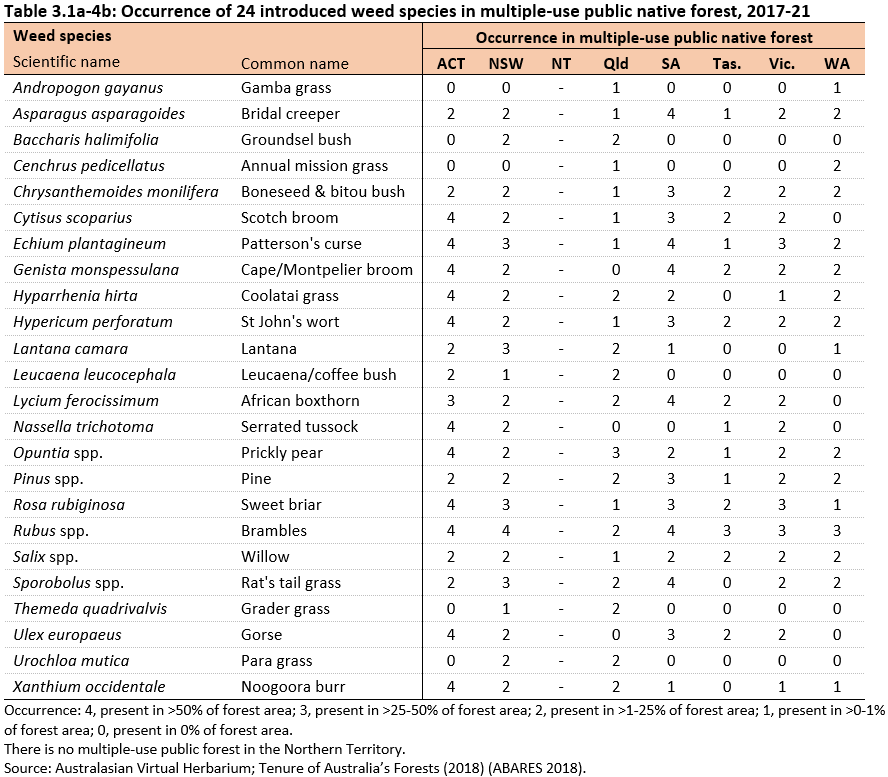

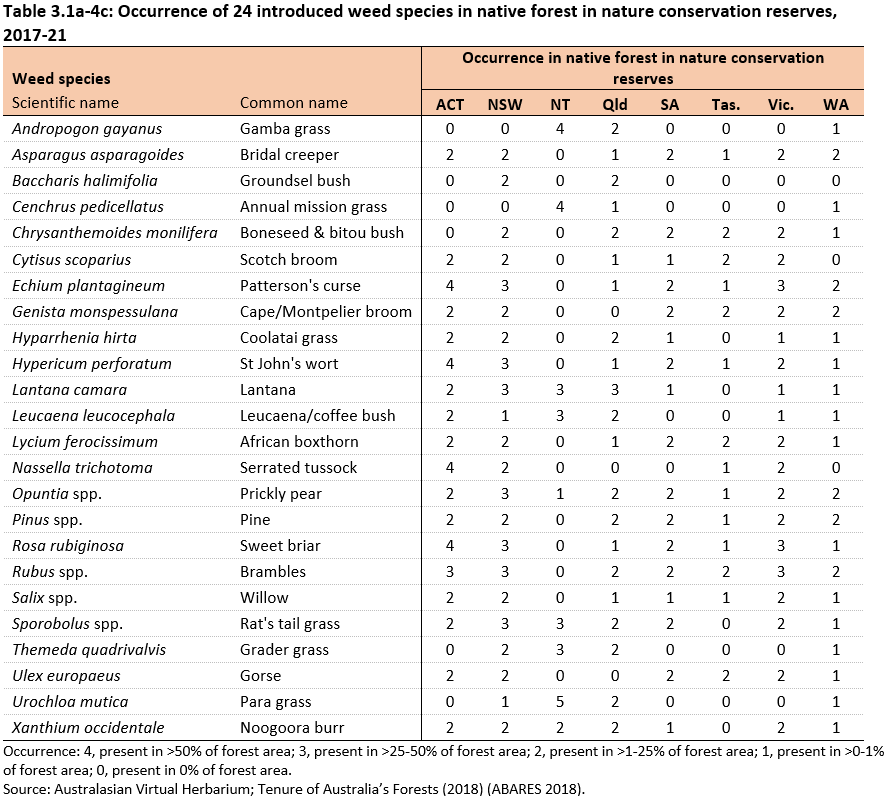

Around 3,500 introduced plant species, many of which are considered weeds, are known in Australia (Martín-Forés et al. 2023). Of these, the 24 weeds most reported by states and territories in Australia’s State of the Forests Report 2018 were analysed against three forest classes (commercial plantations, multiple-use public native forests and native forest in nature conservation reserves) (Tables 3.1a-4a, b, c) (see Supporting information for Indicator 3.1a for methods).

The most widespread weed is prickly pear (Opuntia spp.), which is the only weed of the 24 reported that occur in forests in all states and territories. Thirteen of the 24 weed species occur in forests in all but one state or territory, including brambles (Rubus spp.) and Patterson’s curse (Echium plantagineum).

The Northern Territory has the lowest number of the 24 weed species present in forests (9), while New South Wales has the most (22). Forests in the Australian Capital Territory and New South Wales have the highest overall occurrence of weeds by area, and the Northern Territory and Tasmania has the lowest.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 3.1a-4a.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 3.1a-4b.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 3.1a-4c.

Climate had a large influence on the health and vitality of Australia’s forests during the 2017-21 period. This is reflected in changes over that period in the forest canopy, which is measured as the national average leaf area index (LAI, the projected leaf area per unit area of ground surface):

- The LAI was relatively stable from 2012 to 2017, then progressively declined between 2017 and 2019 as drought conditions intensified; 2019 was Australia’s driest year on record

- LAI recovered in 2020-21 following above-average rainfall over much of the continent.

The period 2017-21 was also the hottest five-year period in the past 100 years. All years between 2017 and 2021 had above-average temperatures, and 2019 was the hottest year on record. Many parts of Australia experienced record-breaking heatwave events during the period. Impacts on health and vitality of forests included:

- Mass tree deaths in north-eastern Tasmania in late 2017, large portions of the Murray-Darling Basin region of New South Wales in late 2019, and in north-western Northern Territory in 2019-20, associated with heatwaves coinciding with drought conditions.

- Mass deaths of flying foxes, including an estimated 23,000 nationally Endangered spectacled flying fox (Pteropus conspicillatus) in northern Queensland in November 2018, and more than 72,000 flying foxes, including the nationally Vulnerable grey headed flying fox (P. poliocephalus) in coastal south-east Australia over the summer of 2018-19.

- Mistletoe (Amyema miquelii) was virtually eliminated from Eucalyptus moluccana and E. fibrosa trees in the Critically Endangered Cumberland Plains Woodland community in the Sydney Basin due to the record heatwave conditions during the 2019-20 summer. Mistletoe is a crucial food source for several birds, mammals and insects.

- Below-average carbon uptake by forests, as measured by carbon dioxide fluxes at several Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network monitoring sites (Beringer et al. 2022), indicating reduced photosynthesis and subsequently reduced growth rates.

Tropical cyclones Owen (December 2018) and Trevor (March 2019) caused extensive damage to mangroves recovering from a 2015 dieback event, caused by combined low sea levels and several climatic anomalies, along 600 km of coastline between the Limmen and Calvert estuaries of the Gulf of Carpentaria.

The long-term effects of climate change in tropical rainforests have been revealed from analysis of 50 years of forest monitoring data in North Queensland (Bauman et al. 2022). Mortality rates have doubled for most tree species, indicating a potential halving in life expectancy and a subsequent reduction in the amount of carbon stored in these forests.

ABARES (2016). The Australian Land Use and Management Classification Version 8, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra. CC BY 3.0.

ABARES (2018). Tenure of Australia’s Forests (2018), Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra, December. CC BY 4.0 doi.org/10.25814/5c592792c780e

Bauman D, Fortunel C, Delhaye G, Malhi Y, Cernusak LA, Bentley LP, Rifai SW, Aguirre-Gutiérrez J, Menor IO, Phillips OL, McNellis BE, Bradford M, Laurance SGW, Hutchinson MF, Dempsey R, Santos-Andrade PE, Ninantay-Rivera HR, Chambi Paucar JR, McMahon SM (2022). Tropical tree mortality has increased with rising atmospheric water stress, Nature 608(7923):528-533. doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04737-7

Beringer J, Moore CE, Cleverly J, Campbell DI, Cleugh H, De Kauwe MG, Kirschbaum MUF, Griebel A, Grover S, Huete A, Hutley LB, Laubach J, Van Niel T, Arndt SK, Bennett AC, Cernusak LA, Eamus D, Ewenz CM, Goodrich JP, Jiang M, Hinko-Najera N, Isaac P, Hobeichi S, Knauer J, Koerber GR, Liddell M, Ma X, Macfarlane C, McHugh ID, Medlyn BE, Meyer WS, Norton AJ, Owens J, Pitman A, Pendall E, Prober SM, Ray RL, Restrepo-Coupe N, Rifai SW, Rowlings D, Schipper L, Silberstein RP, Teckentrup L, Thompson SE, Ukkola AM, Wall A, Wang Y-P, Wardlaw TJ, Woodgate W (2022). Bridge to the future: Important lessons from 20 years of ecosystem observations made by the OzFlux network, Global Change Biology 28(11), 3489–3514. doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16141

DCCEEW (2022). Bushfire recovery quarterly summary November 2022. Australian Government Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Canberra.

Martín-Forés I, Guerin GR, Lewis D, Gallagher RV, Vilà M, Catford JA, Pauchard A, Sparrow B (2023). The Alien Flora of Australia (AFA), a unified Australian national dataset on plant invasion, Scientific Data 10:834. doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02746-3

van Dijk AIJM and Rahman J (2019). Synthesising multiple observations into annual environmental condition reports: the OzWALD system and Australia’s Environment Explorer, 23rd International Congress on Modelling and Simulation, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

Further information

- Methods