Authors: Nicole Byrne and Jarrad Sanderson, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment

Infectious bursal disease (very virulent form)

Infectious bursal disease (IBD) or Gumboro is a viral disease affecting the immune system of young chickens. Present worldwide, the disease is highly contagious in young birds and destroys lymphoid organs, specifically the bursa of Fabricius. Symptoms include depression, watery diarrhoea, ruffled feathers and dehydration. Presentation of clinical signs depends on the strain of the virus and presence of maternal immunity.

Chickens less than 3 weeks of age infected with IBD have subclinical infections which can cause severe, long-lasting suppression of the immune system.Immunosuppressed chickens respond poorly to vaccination and are more susceptible to other diseases, making IBD an economically important disease.

Aetiology

The virus that causes IBD is a double-stranded, non-enveloped, ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus, belonging to the genus Avibirnavirus in the family Birnaviridae. It is very resistant to dessication and can persist in the environment for extended periods. The virus is most easily isolated from the bursa of Fabricius.

Infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) strains are classified into two serotypes but only serotype 1 causes disease in chickens. Serotype 2 infections are non-pathogenic. IBDV has been identified in other avian species, and antibodies to the virus have been found in several wild bird species. Wild birds may thus play a role in the spread of IBDV.

The serotype 1 strains can be further classified based on phenotypic traits such as virulence and antigenicity. Serotype 1 IBD virus classifications are attenuated (vaccine strains), classical (cIBDV), variant (varIBDV) or very virulent (vvIBDV).

The natural reservoir hosts of IBD are chickens (serotype 1) and turkeys (serotype 2).

Distribution

Global

Classical serotype 1 IBDV strains are endemic globally. The vvIBDV strain is endemic in parts of southern Asia, Indonesia, Middle East, Africa and south America, spreading to north America in 2008.

For the latest information on the distribution of IBD, refer to the WAHIS information database website of the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) or the FAO EMPRESi Global Animal Disease Information System.

Australia

In Australia, both classical and variant strains are present, but these are genetically different from the classical, variant and very virulent strains found overseas. Australia remains free from vvIBDV.

Vaccination

In Australia, commercial broiler and layer breeder flocks are vaccinated against IBDV so they are antibody positive. Commonly, breeder birds are vaccinated at about 8-12 weeks with a live vaccine, followed by an inactivated vaccine before point of lay. Transfer of maternal antibodies to progeny birds usually provide enough protection against the field virus challenges. In Australia, chickens less than 6 weeks old are usually not vaccinated.

Transmission

The IBDV is spread horizontally from infected to healthy chickens via the faecal-oral or respiratory route. Disease transmission is by direct contact with excretions from infected birds, or indirect contact with mechanical vectors and fomites. The virus is extremely resistant in the environment, increasing the likelihood of indirect transmission. The virus is also highly resistant to heat and chemicals and can last 4 months in contaminated bedding and premises.

Clinical disease

The incubation period in clinical infections is usually very short, approximately 2 to 3 days. Clinical signs in the acute phase of the disease include anorexia, watery diarrhoea and ruffled feathers. Mortality peaks by day 4 and then subsides, with the surviving chickens recovering to a state of apparent health after about 7 days. This is dependent on the age and breed of chickens, the virulence of the strain and presence of maternal antibodies.

A prominent characteristic of vvIBDV is the ability to induce high mortality. Mortality ranges from 5% - 25% in broilers and 30% - 70% in layers (Ignjatovic 2004). Syndromes of clinical disease are similar to classical virulent strains. However, clinical signs are more acute in individual birds and subacute in flocks.

Diagnosis

IBDV should be considered when birds present with very high morbidity and severe depression lasting 5-7 days. The rate of mortality is variable depending on the virulence of the IBD virus strain. Differential diagnoses include Newcastle disease, acute coccidiosis, infectious bronchitis, Marek’s disease, avian influenza, stress, water deprivation and intoxication, and haemorrhagic syndrome due to sulfa drug toxicity or other causes.

Preliminary diagnosis for IBD can be achieved by observations of clinical signs and gross lesions in the bursa of Fabricius located in the cloaca. Laboratory testing is required for isolation and identification of IBDV. Laboratory tests performed for IBD diagnosis depend on the presences of specific antibodies to the virus, or on the presences of the virus in tissues, using immunological or molecular methods. Where IBD is suspected, samples should be collected from both live, clinically diseased chickens, and recently deceased birds. At a minimum, collect:

- fresh serum from live birds (for serology)

- bursa of Fabricius, spleen and faeces (fresh samples for antigen detection and virus isolation)

- bursa of Fabricius, spleen and thymus (in formalin for histopathological confirmation) and any other lesions (for histopathological differential diagnosis).

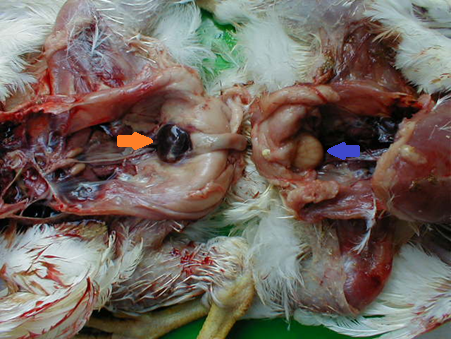

Blood and fresh tissue samples should be chilled and transported at 4°C with frozen gel packs. Formalin fixed samples can be transported at room temperature. Do not freeze samples at -20°C or below as it reduces the sensitivity of virus isolation and molecular diagnostic tests. Lesions seen on post-mortem will depend on the strain of the IBDV. For pathogenic strains of the virus, the bursa of Fabricius is swollen, oedematous, yellow in colour and occasionally haemorrhagic.

Lesions seen in vvIBDV are more obvious with haemorrhage in the bursa of Fabricius and musculature tissue, with rapid atrophy of the bursa and thymus.

Chickens that have recovered from the disease will have a small, atrophied bursa of Fabricius due to lack of regeneration of affected bursal follicles.

Source: Lucien Mahin – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15772580

Risk to Australia of introduction of vvIBDV

Exotic strains of IBDV, including vvIBDV, are found in many countries, including neighbouring Asian countries. This poses a threat to the Australian poultry industry as the virus could be introduced to Australia through illegal importation of infected birds, contaminated poultry products or contaminated fomites transported unintentionally by farm workers.

If an outbreak of vvIBDV occurred in Australia, the economic impact would be significant for Australia’s poultry industry. The outbreak would cause significant losses from death of birds, the cost of control or eradication, and potentially loss of international market access.

Control

If exotic strains of IBD virus, including vvIBDV were to occur in Australia, the policy as described in AUSVETPLAN is to eradicate the disease through activities such as destruction of poultry, quarantine and movement controls, decontamination, product recall, tracing and surveillance.

The implementation of control measures takes into account the highly resistant nature of the pathogen, the ease of spread on fomites and that early detection of certain strains can be difficult.

For further details on Australia’s response policy, see the AUSVETPLAN Infectious bursal disease response strategy located on Animal Health Australia’s website: https://animalhealthaustralia.com.au/ausvetplan/

Keeping Australia free from vvIBDV

Australia has robust farm biosecurity and quarantine measures in place to support the early detection and response of new strains of IBDV. These include mandatory disease notification procedures, emergency animal disease preparedness and response procedures, and animal disease surveillance programs.

Stringent biosecurity policies and border controls further reduce the risk of introducing exotic strains of IBDV into the country, and strict import regulations exist for poultry and poultry products.

Infection with both vvIBDV and exotic strains of varIBDV are reportable throughout Australia. For further information see the National list of notifiable animal diseases.

How Australian veterinarians can help

Under Australia’s current quarantine protocols and importation restrictions, the risk of vvIBDV introduction is regarded as low. However, it is important that Australian veterinarians maintain current knowledge and remain alert to the possibility of emergency disease incursions, as early detection and laboratory confirmation are critical for a rapid and effective response.

Veterinarians can also encourage clients with poultry to practise good farm biosecurity.

Unusual cases of disease, particularly when an emergency animal disease (EAD) is suspected, should be reported directly to state or territory government veterinarians or through the Emergency Animal Disease Watch Hotline (1800 675 888). If you see clinical signs that indicate an EAD like vvIBD, contact your state or territory government veterinarian who will tell you if the investigation could be pursued as a significant disease investigation. If your case is approved, costs will be subsidised by government as part of ensuring Australia maintains disease freedom and rapidly detects any incursion of an EAD.

References

Animal Health Australia (2021). Response strategy: Infectious bursal disease (hypervirulent form) (Version 5.0). Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN), Edition 5, Primary Industries Ministerial Council, Canberra, ACT.

FAO (2021) AVIS – Poultry diseases – Overview. FAO, Rome (Accessed 10 Nov 21).

Ignjatovic J (2004). Very Virulent Infectious Bursal Disease Virus. The Australian and New Zealand standard diagnostic procedure (ANZSDP), CSIRO Livestock Industries AAHL, Geelong, VIC.

MSD Manual Veterinary Manual (2019) Infectious Bursal Disease in Poultry (Gumboro disease). MSD, Kenilworth, New Jersey, USA (Accessed 9 Nov 21).

OIE (2018) Infectious Bursal Disease. OIE, Paris (Accessed 4 Nov 21).