Authors: Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (with thanks to Dr Frank Wong of the Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness for his review and comments.)

Avian influenza

Avian influenza (AI) is a highly contagious viral disease of birds which may take the form of high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) or low pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI). Avian influenza virus (AIV) infection can affect all bird species and can cause severe disease in poultry. Rarely, it can also affect other species including humans. Infection in flocks with LPAI viruses usually causes mild disease or is subclinical but mortality can reach 100 per cent in the acute form of HPAI.

Infection with influenza A viruses in birds is nationally notifiable, while HPAI and H5/H7 LPAI viruses are listed as notifiable diseases by the World Organisation for Animal health (OIE).

Aetiology

AI is caused by the influenza A virus, which is an enveloped, single-stranded negative-sense RNA virus in the family Orthomyxoviridae, genus Influenza A. Influenza A viruses have two surface antigens haemagglutinin and neuraminidase. Avian viruses have 16 subtypes of haemagglutinin antigen (H1-16) and nine subtypes of neuraminidase antigen (N1-9).

Multiple lineages and strains of AIV have been classified based on AIV sequence analysis and distribution of the viruses in different hosts, geographic locations and time. AIVs constantly evolve by error-prone replication (mutation) and reassortment resulting in ongoing emergence of new lineages and reassortants. Wild waterfowl and shorebirds (which rarely show disease) are the natural reservoir hosts for all subtypes of AIV.

HPAI and LPAI are distinguishable by lethality in chickens as well as by molecular sequence in the haemagglutinin protein of the virus. Only H5 and H7 AIVs are known to cause HPAI, and H5 and H7 LPAI viruses may potentially mutate into HPAI especially following passage in poultry flocks. LPAI viruses typically replicate in host respiratory and intestinal epithelial cells while HPAI viruses replicate in many cell types (including heart and brain) thus rapidly resulting in lethal systemic disease.

Distribution

Global

LPAI and HPAI viruses of all H and N subtypes are endemic in wild waterfowl and shorebirds globally. LPAI (clinical and subclinical) and HPAI outbreaks occur in poultry flocks globally, linked to the circulation of viruses in wild migratory birds and live poultry markets.

For the latest information on the distribution of AI, refer to the WAHIS information database website of the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) or the FAO EMPRESi Global Animal Disease Information System.

Australia

Since 1976, there have been eight outbreaks due to HPAI H7 viruses in commercial poultry operations in Australia, with the most recent in Victoria in 2020. It is believed that these outbreaks were most likely caused by introduction of local wild bird LPAI viruses to a free-range flock and subsequent development of LPAI to HPAI after circulation in poultry.

LPAI viruses are commonly detected in wild birds in Australia—visit the Wildlife Health Australia (WHA) website to find out more—but research suggests incursions of overseas AIVs into Australia are infrequent (Bhatta et al. 2020).

Transmission

AIVs can survive in aerosols, water, faeces and litter (the virus can survive within the poultry house environment for up to five weeks). Survival is prolonged by high relative humidity and low temperature. The length of time birds remain contagious varies however most chickens excrete LPAI viruses for 1–2 weeks whereas HPAI viruses usually cause rapid death.

Bird to bird

Transmission between birds may occur when susceptible birds have direct or indirect contact with infected faeces or respiratory secretions. Infected birds can spread virus as early as 24 hours after infection which may be during the incubation period and before the onset of clinical signs. Transmission between flocks may occur through movement of infected birds or fomites such as vehicles, equipment, personnel and feedstuff.

From wild birds to domestic poultry

LPAI viruses can spill over from wild bird populations into poultry. The risk of introduction from wild birds to poultry is increased in flocks that have poor biosecurity practices, such as opportunities for frequent contact between wild birds and domestic poultry, or shared feed and water sources such as dams.

From birds to humans

Avian influenza viruses rarely affect humans. When infection has occurred, it has been due to close contact with infected poultry or materials contaminated with poultry feathers, faeces or other waste from poultry facilities. Eggs and chicken meat are safe to eat provided they are handled and cooked as per standard food handling practices.

Clinical disease

Domestic poultry species most susceptible to AI are chickens, turkey, guinea fowl, quail and pheasants. Waterfowl (particularly ducks) are typically resistant to disease, but HPAI viruses may still cause mortalities

In domestic poultry, the incubation period of AI can vary from hours to up to 2–3 days in individual birds depending on the strain and up to 2 weeks in a flock.

Uncontrolled H5 or H7 LPAI infections have been known to mutate into virulent HPAI infections.

LPAI viruses usually cause subclinical infections or mild respiratory disease in poultry, with high morbidity (>50 per cent) and low mortality (<5 per cent). Clinical presentations include respiratory signs of varying severity, including coughing, sneezing, rales, rattles, nasal discharge and excessive lacrimation. General clinical signs include huddling, ruffled feathers, listlessness, decreased feed and water consumption, diarrhoea and reduced egg production (in layers and breeders).

While there are no clinical signs pathognomonic for HPAI, signs in chickens may include:

- sudden onset of disease and rapid death (in very severe, peracute forms)

- severe respiratory signs, profuse watery diarrhoea, oedema and cyanosis of the unfeathered skin and combs, ecchymoses on the shanks and feet, swelling of the face, coughing and neurological signs

- depressed birds with reduced egg quality and reduced egg production that is more pronounced than with LPAI.

Clinical signs in other gallinaceous birds (such as turkeys and quail) are similar to chickens. However, there are cases where H5 or H7 AIVs have caused only mild illness in chickens and turkeys despite being classified as HPAI virus by molecular pathotyping.

Ducks, geese, swans and other waterbirds may become infected with and transmit AI viruses. but rarely display clinical signs of infection.

Diagnosis

Many other viral and bacterial pathogens of chickens can present with similar clinical signs or cause concomitant infections with AI. It is important to take into consideration that an AIV infection may be masked by other underlying infections, and AI should be tested for if the clinical signs and pathology are present. This is especially important considering the spectrum of signs that can be seen with LPAI.

Post-mortem findings may include (for LPAI): gross lesions (variable depending on the virus strain, host species and presence of secondary infection), swollen infraorbital sinuses with accompanying mucoid nasal discharge, rhinitis and sinusitis lesions, oedematous and congested tracheal mucosa.

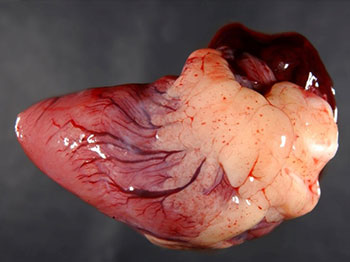

With HPAI, post-mortem findings may include: gross lesions (depending on the stage of infection), necrosis and cyanosis of the comb and wattles are common (subcutaneous oedema is also evident around the head, legs and feet, along with ecchymotic subcutaneous haemorrhages), focal haemorrhages of the internal organs, particularly in the trachea, coronary fat, epicardium, proventriculus, Peyer’s patches and caecal tonsils.

(Source: USDA, Plum Island Animal Disease Center)

(Source: USDA, Plum Island Animal Disease Center)

(Source: USDA, Plum Island Animal Disease Center)

Differential diagnosis

HPAI should be suspected whenever sudden bird deaths occur with severe depression, loss of appetite, nervous signs, watery diarrhoea, severe respiratory signs and/or a drastic drop in egg production accompanied by the production of abnormal eggs. The likelihood of AI is increased by the presence of facial subcutaneous oedema, swollen and cyanotic combs and wattles, and petechial haemorrhages on the internal membrane surfaces.

Consider in the differential diagnosis: duck viral enteritis, Newcastle disease, avian chlamydiosis, bacterial septicaemia, cellulitis of the comb and wattles, fowl cholera, infectious bronchitis, infectious coryza, infectious laryngotracheitis and mycoplasmosis.

Sampling

Where AI is suspected, collect:

- tracheal, or oropharyngeal and cloacal and/or faecal swabs from live, clinically affected birds

- serum from birds suspected to have been clinically affected for a number of days (at least seven birds) or recovered birds

- fresh tissue samples and whole blood (EDTA tube, 2 ml/bird) from clinically affected birds (killed immediately before a post-mortem examination) and from any recently dead birds.

Fresh tissue should include: samples from the brain, proventriculus, pancreas, intestine, liver, caecal tonsil, trachea, lungs and cloaca; impression smears of the bursa of Fabricius, pancreas, brain, and spleen; a full range of tissues in neutral-buffered formalin (including the brain, proventriculus, pancreas, intestine, liver, caecal tonsil, trachea, lung, bursa, kidney and cloaca) and; several whole birds (at least 5 birds) for post-mortem examination, as there may be great variability in lesions presented in individual animals. A composite picture of all lesions seen should be recorded.

For transport, blood and fresh tissue samples should be chilled and transported at 4°C with frozen gel packs. Formalin fixed samples can be transported at room temperature. Do not freeze samples at -20°C or below as it reduces the sensitivity of virus isolation and molecular diagnostic tests.

Control and personal protective equipment

AI is a public health risk and the zoonotic risk must be taken into consideration when investigating an outbreak of sudden deaths, gastrointestinal or respiratory disease in poultry. Therefore, it is important to seek advice from government veterinary authorities about biocontainment and personal protective equipment.

In the event of an AI outbreak, the official response policy of Australia is to determine the pathotype of the virus strain so that an appropriate control strategy can be formulated. Stamping out for the purpose of eradication is the preferred option. Vaccination, with government control, may be considered as one element of a comprehensive control program if eradication is not feasible.

Refer to the AUSVETPLAN Avian Influenza disease manual for a more comprehensive explanation of Australia’s prevention and response policy.

Preventing AI in poultry in Australia

LPAI viruses known to circulate in Australian wild birds remain a constant biosecurity threat to Australian poultry through direct or indirect (e.g., contaminated drinking water) contact. Recent AIV outbreaks in Victoria in commercial poultry in 2020 were due to strains of AIVs closely related to LPAI viruses circulating in Australian wild bird reservoir species, and not an imported AIV strain from Asia or elsewhere. Thus, farm biosecurity plays a key role.

Australia also has well-developed systems to support the early detection of and response to animal diseases and pests, including AI. These include mandatory notifiable disease notification procedures, emergency animal disease preparedness and response activities, and animal disease surveillance activities. Both targeted and general surveillance of AI in wild birds is performed under the National Avian Influenza Wild Bird (NAIWB) surveillance program, and sequence analysis of AIV detected in wild birds through this national program contributes to tracking Australian virus evolution and dynamics, and maintaining the currency of diagnostic tests.

Australia further reduces the risk of introduction of exotic strains of AI and a range of other poultry diseases through the enforcement of strict biosecurity policies and border controls. Australia’s focus is on ensuring that the level of risk in products that arrive at its borders is already managed to acceptable levels. Stringent, scientifically informed import regulations are in place for poultry and poultry products. The import regulations are supported by rigorous inspection and biosecurity protocols at Australia’s national borders.

All Australian jurisdictions require that any AIV infection is reported to the relevant Chief Veterinary Officer (CVO). The national notifiable diseases list does not specify strains of AI but requires reporting of any type of influenza A virus infection in birds. For further information see National list of notifiable animal diseases

Risk to Australia of introduction of exotic strains of AI

Of global concern is the capacity of AIV subtypes H5 and H7 to mutate from LPAI into HPAI forms which can cause significant losses in both poultry and wildlife.

In 2020, there were multiple detections of reassortant Asian-lineage HPAI H5 viruses distributed across continents in wild birds and poultry. Based on 2020 reports to the OIE1, a high number of new and ongoing HPAI outbreaks were reported by countries, notably in Asia and Europe. However, HPAI viruses circulating in commercial poultry and wild bird populations in the northern hemisphere are not usually considered a threat to Australia since no waterfowl species undertake annual migrations from HPAI affected areas in the northern hemisphere to Australia.

Although previous research has assessed the overall risk of introduction of HPAI to Australia to be low (Curran 2012), the current widespread and abundant circulation of reassortant HPAI viruses in the northern hemisphere could pose an increased level of risk to Australia. Recent Australian research has demonstrated that a migratory shorebird, the red-necked stint, is being exposed to HPAI H5Nx clade 2.3.4.4 viruses along their migratory route between Asia and Australia. Despite this, there is currently no evidence that migratory birds are still carrying infectious HPAI H5Nx clade 2.3.4.4 viruses when they arrive in Australia (Wille et al 2019), and Australia remains free from the HPAI H5Nx clade 2.3.4.4 viruses currently being detected in the northern hemisphere.

How Australian veterinarians can help

Under Australia’s current biosecurity protocols and importation restrictions, the risk of AI introduction is regarded as low. However, it is important that Australian veterinarians maintain current knowledge and remain alert to the possibility of emergency disease incursions as early detection and laboratory confirmation are critical for a rapid and effective response.

Veterinarians can also encourage clients with poultry to practise good farm biosecurity (see guidelines at the Farm Biosecurity website), with a focus on minimizing direct and indirect poultry contact with wild birds, particularly waterfowl. They should also report and investigate unusual and mass sickness and deaths in domestic and wild birds, and encourage others to do so.

Unusual cases of disease, particularly when emergency animal diseases are suspected, should be reported directly to state or territory government veterinarians or through the Emergency Animal Disease Watch Hotline (1800 675 888).

https://www.oie.int/en/animal-health-in-the-world/update-on-avian-influenza/2020/

References

Animal Health Australia. 2011. Disease strategy: Avian influenza (Version 3.4). Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN), Edition 3, Primary Industries Ministerial Council, Canberra, ACT.

Department of Agriculture and CSIRO. 2019. Emergency animal diseases: A field guide for Australian veterinarians, Canberra, August. CC BY 4.0.

Bhatta RB, Chamings A, Vibin J, et al. 2020. Detection of a Reassortant H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus with Intercontinental Gene Segments in a Resident Australian Chestnut Teal. Viruses. 12(1):88. doi: 10.3390/v12010088

Curran, J. 2012. The surveillance and risk assessment of wild birds in northern Australia for highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus. PhD thesis, Murdoch University.

Wille M, Lisovski S, Risely A, et al. Serologic Evidence of Exposure to Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5 Viruses in Migratory Shorebirds, Australia. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2019;25(10):1903-1910. doi:10.3201/eid2510.190699.