Corissa Miller & Richard Niall, Australian Department of Agriculture and Water Resouces, 2015

The cost of classical swine fever

Classical swine fever (CSF), also known as hog cholera, is a highly contagious viral disease of domestic and wild pigs. Due to its high economic burden, it is considered one of the most important diseases of pigs worldwide. CSF is listed as a notifiable disease by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) Terrestrial Animal Health Code, with over 50 countries reporting outbreaks in the past decade1. Australia last eradicated CSF in 1961, and was recently granted official CSF-free status by the OIE. However, the disease remains endemic in many neighbouring countries, and Australia faces the constant threat of re-introduction.

The pork industry is an important contributor to Australian livestock production and the national economy. An outbreak of CSF could have significant impacts on productivity and international market access, and would likely be difficult and costly to eradicate. Integrated epidemiology/economic studies havemodelled the impacts of CSF epidemics in Australia’s primary pig production areas, and estimated gross income losses of up to 37% based on productivity and disposal considerations alone.2 Should CSF become endemic, opportunity losses in gross national pig income of up to 11% per year could be expected, due to the loss of both export market access and local market share.

Aetiology

The causative agent of CSF is classical swine fever virus (CSFV) of the genus Pestivirus, family Flaviviridae, and is closely related to other ruminant Pestiviruses such as bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV).

In Australia, both domestic and feral pigs (Sus scrofa) are susceptible hosts for CSF. Wild pigs have been recognised as sources of infection in a number of outbreaks in endemic countries. Should CSF enter Australia, the feral pig population may act as a reservoir for secondary spread to domestic pigs. Reporting and sampling of suspect feral pigs remains an integral part of effective disease detection and response3. The Northern Australia Quarantine Strategy (NAQS) runs annual disease surveys of feral pigs as part of a targeted surveillance for CSF throughout Northern Australia.

Epidemiology

CSFV spreads rapidly via both direct and indirect pathways. The virus is excreted in high concentrations in oral fluid, but can also be spread through urine, faeces, nasal and lachrymal fluid. Aerosol transmission may occur over short distances. Placental transmission is possible, and in-utero infections can lead to persistently infected (PI) young. Like BVDV, PI animals may not display overt clinical signs, but can become infectious chronic shedders of the virus.

Virus is transmitted principally by direct contact with infected pigs, while indirect transmission occurs via contact with fomites, such as equipment and personnel, or following ingestion of infected pig meat or products. For this reason, the feeding of food scraps or food waste that contains or has come into contact with meat or meat products (swill feeding) is illegal in Australia.

Clinical disease

Figure 2. Pig presenting with ‘skin blotching’

(photo credit: USDA Plum Island Animal Disease Center)

Disease severity varies greatly; influenced by host age, herd immunity and the strain and virulence of CSFV encountered. Pigs infected with CSFV may develop (1) acute, (2) chronic, or (3) subclinical disease, and both clinical signs and case mortality rates are extremely variable. In general, young naive animals are affected more severely, but the emergence of less virulent CSFV strains and milder clinical disease reinforces the need for vigilant testing and reporting of all suspect cases.

Clinical signs of acute CSF may include, but are not limited to: pyrexia (39.5 – 42˚C), inappetance, gastrointestinal and neurological abnormalities, abortion or foetal deformities, conjunctivitis, nasal discharge, and skin haemorrhages and cyanosis (particularly on extremities such as the ears and snout). Case fatality rates can reach 100% following acute highly virulent disease. However, animals with chronic CSF may present with milder clinical signs, including: general ill-thrift, fluctuating pyrexia, pneumonia, alopecia and dermatitis. In the subclinical form of the disease, animals may become chronic carriers without overt clinical signs.

Pathology

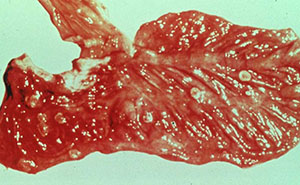

Figure 3. Gastrointestinal button ulcers in a pig with CSF

(photo credit: USDA Plum Island Animal Disease Center)

The most common post-mortem findings in CSF-positive pigs are signs of haemorrhage, such as: petechiae on the kidneys, bladder and lymph nodes; splenic enlargement; gastric ulceration; and pneumonia, pleuritis or bronchitis. The acute form may present with more profound haemorrhaging across all organs, fluid in the body cavities and lungs and pyramidal infarcts along the margin of the spleen. Gross pathology of chronic CSF varies, and is generally indicative of a more prolonged illness. Lesions may include fibrinous pericarditis, pleurisy, button ulcers of the large intestine at the ileocaecal valve, lobular lung consolidation, and thymic atrophy.

Diagnosis

As clinical signs and post-mortem lesions are not unique to CSF, suspicion of the disease must be confirmed by laboratory diagnosis. The samples outlined in Table 1 should be taken from clinically affected, recently dead or killed animals, including aborted foetuses and stillborn piglets.

| Purpose | Required specimen |

|---|---|

| Identification of agent | Whole blood in EDTA anticoagulant (7–10 mL/animal) from live, clinically affected animals. |

| Fresh tissues (approx. 2 g of each tissue) collected aseptically post-mortem and forwarded unpreserved: spleen, tonsils, lymph nodes, kidney and distal ileum; other tissues such as lung and liver may be included principally for differential diagnostic workup. | |

| Serological testing | Sera from suspected chronic or recovered cases (including sows suspected to have had piglets with disease), and in-contact pigs (30 samples recommended in suspected herd). |

| Histopathology | A full range of tissues (including the brain) in neutral-buffered formalin. Histopathology findings are not pathognomonic for CSF but histopathology can provide additional support for differential diagnoses. |

Protecting Australia from CSF

Outbreaks of CSF have previously occurred in Australia in 1903, 1927–28, 1942–43 and 1960–61. In each case, the disease was eradicated. CSF is a notifiable disease under Australian legislation, and early outbreak detection and response is essential to minimise productivity and trade losses. In the event of a CSF outbreak, Australia’s policy is to control and eradicate the disease in the shortest possible time using a combination of strategies, including stamping out and movement controls. The Government and Livestock Industry Cost Sharing Deed in Respect of Emergency Animal Disease Responses (EADRA) outlines the government and industry cost-sharing arrangements to fund such a response. Actions taken by Australia in response to a CSF incursion would vary depending on host and agent factors and the extent, location and stage of the outbreak. The Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN) Disease Strategy for Classical Swine Fever4 provides comprehensive control, eradication and post-outbreak surveillance guidelines.

Keeping Australia CSF free

Australia maintains a CSF-free status and greatly reduces the risk of incursion through the enforcement of strict biosecurity policies. Stringent import regulations exist for pork and pork products. Swill feeding is illegal under Australian legislation. At a federal level, the Department of Agriculture enforces rigorous inspection and quarantine protocols at Australia’s national borders, and conducts off-shore disease surveillance and risk mitigation activities in Australia’s close neighbours, including Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea. An on-shore targeted surveillance program runs under the Northern Australia Quarantine Strategy (NAQS) to provide an early warning system for exotic disease incursions and to meet OIE criteria for negative reporting and general surveillance.

The risk of introduction

Illegal importation of CSVF-infected pig products or genetic material remains the most likely source for entry of CSF into Australia. Although swill feeding is prohibited, unlawful or inadvertent feeding of imported infected products to domestic or feral pigs presents the greatest risk, and is believed to be the source of Australia’s previous CSF outbreaks. Contaminated products may arrive from endemic countries via commercial aircrafts or ships, the international postal service, or the waste disposal of fishing vessels. As Australia’s modern intensive piggeries practice a high level of biosecurity, the most likely entry points of infection may be smaller commercial or backyard establishments, or scavenging feral pigs.

How Australian veterinarians can help

Under Australia’s current quarantine protocols and importation restrictions, the risk of CSF introduction is regarded as low. However, mild disease due to low-virulence CSFV strains can be difficult to detect, and may result in delayed responses and more significant outbreak impacts. It is therefore important that Australian veterinarians maintain current knowledge and remain alert to exotic disease risks, to ensure rapid recognition and response to a potential outbreak. Early detection and laboratory confirmation of CSF is key to effective disease control.

If you suspect an exotic disease, please contact the Emergency Animal Disease Watch Hotline on 1800 675 888 for advice and assistance.

Further reading

1 World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). World Animal Health Information Database (WAHID) Interface. Accessed 03 August 2015.

2Garner M.G., Whan I.F., Gard G.P. & Philips D. 2001, ‘The Expected Economic Impact of Selected Exotic Diseases on the Pig Industry of Australia,’ Revue Scientifique et Technique Office International des Epizooties, vol. 20, no. 3, pp 671 – 685.

3 Wildlife Health Australia. Exotic Fact Sheet: Classical Swine Fever. Accessed 03 August 2015.

4Animal Health Australia 2012, Disease Strategy: Classical swine fever (version 3.1), Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN), Edition 3, Standing Council on Primary Industries, Canberra, ACT.