Authors: Rhys Downham, John Walsh, Tim Westwood and Mihir Gupta

Data visualisation

Source: ABARES

The PowerBI dashboard may not meet accessibility requirements. For information about the contents of these dashboards contact ABARES.

Summary

The purpose of this report is to provide forecasts for water allocation prices and irrigation activity in the southern Murray–Darling Basin (sMDB) for the year ahead (2022–23). Prices are forecast under four representative scenarios aligned with state water agency allocation outlooks: ‘extreme dry’, ‘dry’, ‘average’ and ‘wet’. A summary of current market conditions in 2021–22 is provided as context for the likely market outcomes in 2022–23.

ABARES considers the average scenario to be most likely for 2022–23, based on the current climate outlook from the BOM which indicates a return to neutral seasonal conditions. The forecasts presented in this report are based on the latest data from the BOM and state water agencies, and changes in this underlying data will result in changes to the forecasts. Readers should consult the BOM and state water agency websites to keep up to date with the latest outlook for seasonal conditions and water supply.

| 2021–22 | Extreme dry | Dry | Average | Wet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $77 | $150 | $102 | $80 | $57 |

Prices are forecast to remain low for a third consecutive year

The annual average water allocation price in the sMDB is forecast to remain low in 2022–23 at $80 per ML in the average scenario. However, there are some regional differences, as the inter-valley trade (IVT) limits continue to play a role in affecting water market outcomes in the sMDB. For instance, in the dry and extreme dry scenarios, as the overall water supply in the sMDB decreases and demand increases, prices increase in all regions except Northern Victoria where the Goulburn IVT is forecast to restrict water trade from the Goulburn to the Murray.

Prices are also forecast to increase under all scenarios in the Murrumbidgee where NSW has currently forecast lower allocations relative to other regions. This will likely create pent-up demand for water in this region that cannot be fulfilled through trade since the Murrumbidgee is upstream of other regions and cannot import water.

The price of water typically varies dramatically depending on seasonal conditions, with lower prices in wet years ($71 per ML in 2016–17) and higher prices in dry years ($596 per ML in 2019–20). However, the difference in prices across the forecast scenarios for 2022–23 is quite small, with only a $93 per ML difference between the wet and extreme dry scenarios. This reflects the highly favourable water supply conditions forecast for next year.

Favourable water supply conditions are likely in 2022–23

Back-to-back years with high water availability and rainfall have led to reduced irrigation water demand in 2021–22. Irrigators have been able to rely on rainfall and water carried over from the previous year and have made limited use of water allocated in 2021–22. Substantial volumes of water are expected to remain unused by the end of this year (particularly in the Murray). This will lead to carryover balances at or near carryover limits into 2022-23 and significant end-of-year water forfeitures (that are also contributing to the high allocations forecast for next year).

Most of the major entitlements in the sMDB are forecast to reach 100% allocation in 2022–23 under the wet, average and dry scenarios. High allocations are even forecast in the extreme dry scenario in Victoria (67% for the Goulburn and 90% for the Murray). State allocation outlooks also indicate that opening allocations for 2022–23 are likely to be higher than this year for most entitlements. Combined with high carryover levels, this means there is more certainty about water availability at the start of the 2022–23 water year, allowing irrigators to make more informed planting decisions.

Water availability was high across the southern Basin

The amount of water available for irrigation in the southern Murray–Darling Basin (sMDB) in 2021–22 is at the highest level since 2012–13. This is also reflected in water allocation prices, with an average annual price of $77 per ML across the sMDB. The reason for this is two-fold:

- Back-to-back La Niña events have contributed to consecutive years of above average rainfall and renewed storages, and

- High inflows in 2020–21 boosted storages and resulted in high allocations and large volumes of water being carried over into the current year.

Water storages are at the highest level since 2012–13

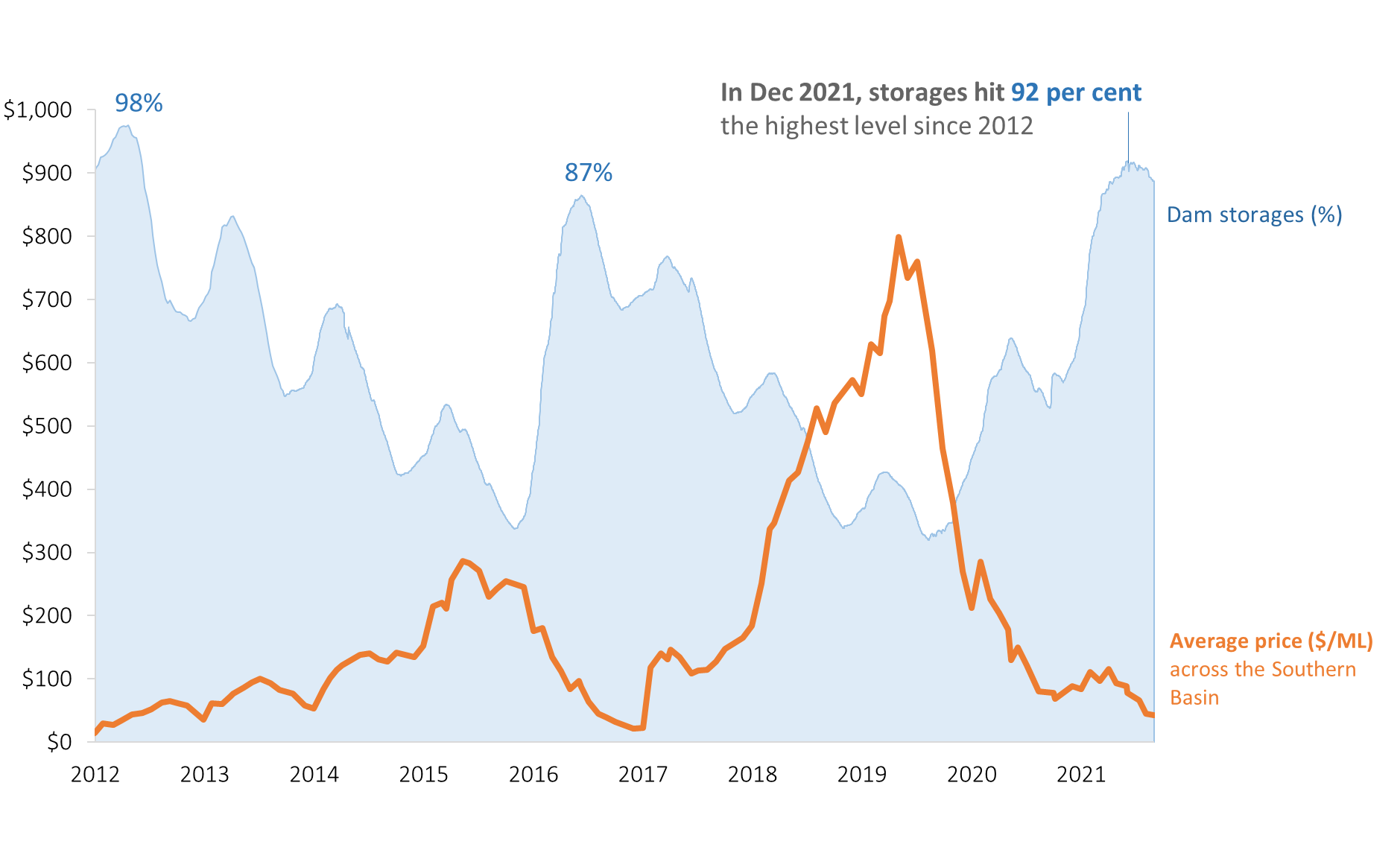

Back-to-back years with La Niña and negative Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) events have led to significant inflows to dam storages, with MDB storages peaking at 92% in December 2021 (Figure 1). The moderate and late-forming La Niña event in 2021–22 contributed to above average rainfall in most sMDB regions, but has since peaked, with conditions expected to return to neutral in late autumn 2022 (BOM 2022).

Figure 1 Water storages and average price in the Murray–Darling Basin, 2012 to 2022

Note: Dam storages are reported for the Murray–Darling Basin as a percentage of total capacity. Price is volume weighted average for the southern Murray–Darling Basin in 2020–21 dollars.

The Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) climate outlook for the remainder of 2021–22 forecasts above median rainfall for much of eastern Australia despite weakening climate influences (BOM 2022). Although the unseasonably high inflows into storages during early summer appear to have slowed (ABARES 2022c), reduced irrigation water use has kept water storages high. Water storages in the sMDB started the 2021–22 year at 61% capacity and have increased to 89% by 16 March 2022, the highest level since 2012–13 (BOM 2021, MDBA 2022).

Large carryover volumes have boosted water availability

The amount of water available for irrigation in 2021–22 was further boosted by large volumes of water carried over from the previous year. For most major entitlements, the amount of water carried over into 2021–22 was the highest since 2012–13. Consecutive wet years have allowed irrigators to rely more on rainfall in 2021–22 and less on regulated surface water from rivers.

As a result, substantial volumes of unused water are expected by the end of this year, leading to carryover balances at or near carryover limits and significant end-of-year water forfeitures. Current unused water balances for NSW Murray and Murrumbidgee general security entitlements are sitting well above their carryover limits (50% and 30%, respectively). In Victoria, unused water is sitting at 90% against Goulburn high reliability entitlements and 84% against Murray entitlements. However, irrigators in Victoria won’t be able to access their carryover water in 2022–23 until a low risk of spill is declared.

The continued improvement in water availability has been reflected in water allocation prices, with an average annual price across the sMDB in 2021–22 of $77 per ML, the lowest price since 2016–17.

All major water entitlements received the maximum allocation

All major water entitlements in the sMDB have received 100% allocation in 2021–22 (Figure 2). Allocations this year were significantly above historical averages and higher than allocations in 2020–21, which also reached 100% allocation for most major entitlements. NSW Murray general security allocations were exceptionally high this year, reaching the maximum 110% allocation (including carryover). A full allocation to this entitlement type represents 1,839 GL of water available for irrigation use (allocation and carryover).

Figure 2 Closing allocations for major entitlements in 2021–22

Low reliability entitlements in the Victorian Murray region received 100% allocation on 15 February 2022, providing irrigators with an additional 312 GL of water (NVRM 2022b). This is the first time since the unbundling of traditional entitlements (into high and low reliability water shares) in 2007 and is a quite a change from historical announcements over the last 20 years. The last time that low reliability entitlements received an allocation was 5% in 2016–17.

Exceptionally high allocations this year are not surprising given the high volumes of water carried over from the 2020–21 and consecutive La Niña years that have contributed to sMDB storages exceeding 90% capacity.

Market conditions provide opportunities for cotton and rice

Significant rainfall at the beginning of 2021–22 has led to increased on and off-farm water storages, boosting plantings of irrigated cotton and rice (ABARES 2022a, ABARES 2022b). The area planted with irrigated cotton in the sMDB in 2021–22 was the highest on record.

Cotton and rice growers have also benefited from high commodity prices and low water prices, leading to increased demand for water in NSW. Internationally, freight disruptions have driven up prices of cotton (ABARES 2022b). Supported by the strongest export prices in a decade, irrigated cotton production hit a record high in 2021–22 (ABARES 2022b).

Restrictions on inter-valley trade continued in 2021–22

As has been the case in recent years, inter-valley trade (IVT) rules have continued to limit trade in 2021–22, resulting in price gaps between regions. This is most clearly seen in Victoria between the Goulburn ($78 per ML) and Victorian Murray below the Barmah Choke ($99 per ML) (Figure 3), as well as in NSW between the Murrumbidgee ($63 per ML) and NSW Murray above the Barmah Choke ($68 per ML).

Figure 3 Price gaps between the Victorian Goulburn and Murray continued in 2021–22

Note: Prices in 2020–21 dollars.

The effect of trade limits is compounded by regional differences in irrigation activity and water demand. Due to the concentration of water-intensive permanent plantings (such as almond and fruit trees) in regions below the Barmah Choke, irrigators in these regions typically have a greater demand for water than irrigators in regions where more opportunistic cropping activities (such as irrigated cotton, rice and pastures) are more prevalent.

Price gaps between regions are typically associated with dry conditions, low water availability and high prices. However, in recent years trade limits have been binding with greater frequency and for longer durations despite favourable conditions. A prime example of this is the Victorian Goulburn to Murray trade limit, which in the past 4 years (2018–2021) has restricted trade for over 1,000 days, compared with 258 days in the preceding 4 years (2014–2017) (Figure 4). While more water has been traded between the Goulburn and Murray in 2021–22, trade between the two regions has remained closed more often than not.

Figure 4 Vic. Goulburn to Murray trade has already been closed for 188 days in 2022

Note: ABARES has assumed that inter-valley trade was closed when the available trade opportunity was less than 10 ML.

ABARES has developed scenarios for water availability in 2022–23 that draw upon the latest allocation outlooks from state water agencies (as at 15 March 2022). Four representative scenarios are considered—‘extreme dry’, ‘dry’, ‘average’ and ‘wet’—that align with the allocation outlooks published by state water agencies. ABARES uses these allocation forecasts and estimates of opening carryover (excluding environmental water) to determine the volume of water available in 2022–23 for irrigation in the southern Murray–Darling Basin (sMDB) under each scenario. See Appendix A for more details.

The scenarios are indicative only, and conditions could be better or worse than forecast, which would in turn affect prices. Readers should consult state water agency forecasts (NSW DPIE, NVRM and SA DEW) and BOM climate outlooks throughout the year to inform their decisions.

ABARES considers the average scenario to be most likely for 2022–23 due to an expected return to neutral climate conditions, based on the latest BOM climate outlook. However, all four outlook scenarios are discussed in each edition of the Water Market Outlook to provide consistent information on the effects of different seasonal conditions and related on-farm decisions such as carryover and irrigation water use.

Neutral climatic conditions are more likely in 2022–23

A neutral El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is most likely for 2022–23 following back-to-back La Niña years (ABARES 2022c). La Niña events are associated with increased rainfall over much of eastern Australia, so a return to neutral conditions would see rainfall in the sMDB returning to average levels. However, with sMDB water storages currently at their highest level since 2012–13 (BOM 2021), water supply is not expected to reduce significantly in 2022–23.

There is a low probability of a third consecutive wet year (La Niña event), as only 25% of all La Niña events on record have lasted 3 years (ABARES 2022c). The probability of returning to dry conditions (El Niño event) in 2022–23 is even lower, with only 15% of all La Niña events since 1970 having been directly followed by an El Niño event.

See ABARES Seasonal conditions: March quarter 2022 for further information regarding the outlook for 2022–23.

Allocation forecasts are high due to good water availability

Most of the major entitlements in the sMDB are forecast to reach 100% allocation in 2022–23 under the wet, average and dry scenarios (Figure 5 ). High allocations are even forecast in the extreme dry scenario in Victoria (67% for the Goulburn and 90% for the Murray). It is unusual to have this much certainty about next year’s water availability this early in the year (allocation outlooks were released on 15 February for Victoria and 15 March for NSW). However, for 2022–23, this is due to the large amounts of water currently sitting unused.

In Victoria, allocations to Murray and Goulburn high reliability entitlements are expected to reach 100% under all but the extreme dry scenario (NVRM 2022a). This is a more favourable outlook for the year ahead than this time last year but is not unexpected because Victorian water storages are currently around 90% capacity and unused water balances indicate that carryover into 2022–23 is likely to be at least as high as this year.

The current allocation outlook for NSW is less favourable, with closing allocations forecast below historical averages in the dry and extreme dry scenarios (NSW DPIE 2022). However, it’s worth noting that the NSW allocation outlook only goes out to November 2022 and allocations may increase further in the second half of 2022–23.

Based on indicative opening allocations, water availability at the start of the year will be much lower in NSW than in Victoria. The outlook for opening allocations in NSW is more conservative than in Victoria, although in the average scenario NSW Murray general security allocations are forecast to reach 100%. Murrumbidgee general security entitlements are also forecast to receive around 49% allocation in this scenario (with NSW DPIE noting the possibility of additional allocations if certain conditions are met – see Appendix A: ABARES outlook scenarios ).

Figure 5 Water allocation scenarios for 2022–23

Note: Historical average of closing allocations calculated over the 20-year period from 2002–03 to 2021–22. NSW DPIE has indicated that Murrumbidgee general security allocations could increase by 5-10% in the average and wet scenarios if certain conditions are met (see Appendix A: ABARES outlook scenarios).

Total water available for irrigation use in the sMDB is forecast to decrease in 2022–23 in all four scenarios, although this is from an incredibly high base in 2021–22 where all major entitlements (and even low reliability entitlements in Victoria) received 100% allocations (Figure 6 ). In the average scenario, water available for irrigation use is forecast to at least remain above 2020–21 levels.

The relatively small difference in water available for irrigation use between the scenarios for next year is primarily because Victorian entitlements are forecast to reach 100% allocations even under dry conditions. Water availability next year is also being boosted in all four scenarios by the large amount of unused water in 2021–22, that is likely to be carried over into 2022–23.

The timing of water availability is also an important consideration for irrigators. State allocation outlooks indicate that opening allocations for 2022–23 are likely to be higher than this year for all major entitlements except NSW Murrumbidgee general security. High water supply at the beginning of 2022–23 from opening allocations and high carryover balances from 2021–22, will provide irrigators greater confidence in their annual crop planting decisions.

Figure 6 Total water available for irrigation use in the sMDB, 2001 to 2023

Note: ‘Water available for irrigation use’ is calculated as the sum of allocations, water carried over from the previous year and any water classified as uncontrolled flows, minus water allocated for the environment and water forfeited during the year. f ABARES forecast.

Water prices are forecast to remain low in 2022–23

Some of the drivers for water prices next year include:

- Irrigators will have access to allocations on par or better than historical averages and large volumes of water carried over from 2021–22.

- Demand for water in regions below the Barmah Choke is expected to remain high in 2022–23, as almond trees continue to mature in this region, following record levels of production in recent years. Demand for water from cotton and rice growers in NSW is expected to be supported by good water availability in 2022–23 (ABARES 2022b).

- Inter-valley trade (IVT) limits will continue to play an important role in determining prices in 2022–23.

Water allocation prices are forecast to remain low in 2022–23, with the weighted average sMDB price in the average scenario forecast to be $80 per ML (Table 1). If the wet scenario eventuates, prices are forecast to decrease from $77 per ML in 2021–22 to $57 per ML next year. In contrast, prices in the dry and extreme dry scenarios are forecast to increase to $102 per ML and $150 per ML, respectively.

The price of water typically varies dramatically depending on seasonal conditions, with lower prices in wet years ($71 per ML in 2016–17) and higher prices in dry years ($596 per ML in 2019–20). However, the difference in prices across the forecast scenarios for 2022–23 is quite small, with only a $93 per ML difference between the wet and extreme dry scenarios. This reflects the highly favourable water supply conditions forecast for next year.

| Region | 2021–22 average ($/ML) |

Extreme dry ($/ML) |

Dry ($/ML) |

Average ($/ML) |

Wet ($/ML) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSW Murrumbidgee | 63 | 222 | 152 | 97 | 69 |

| NSW Murray Above | 68 | 137 | 91 | 77 | 52 |

| VIC Murray Below | 99 | 152 | 109 | 97 | 69 |

| Northern Victoria | 78 | 72 | 37 | 27 | 19 |

| SA Murray | 104 | 152 | 109 | 97 | 69 |

| Weighted sMDB average | 77 | 150 | 102 | 80 | 57 |

Source: ABARES, BOM, Waterflow

Note: Water prices in 2020–21 dollars. Northern Victoria comprises the Goulburn, Broken, Loddon and Campaspe regions. ABARES estimates that NSW Murrumbidgee prices in the average scenario could decrease by $9/ML if certain conditions are met (see Appendix A: ABARES outlook scenarios).

Regional differences in water prices are likely next year, as the inter-valley trade limits (IVT) continue to play a role in affecting water market outcomes in the southern basin. The Barmah Choke and Goulburn to Murray IVT are forecast to restrict water trade in all four scenarios. This is particularly noticeable in the dry and extreme dry scenarios where the overall water supply in the sMDB decreases and water demand increases, especially in the Victorian Murray where horticulture is the dominant irrigation activity.

The combination of higher water demand and binding trade limits means that Murray regions below the Barmah Choke are forecast to experience higher water prices in all scenarios, compared to the average sMDB price.

Prices are also forecast to increase under all scenarios in the Murrumbidgee, where NSW DPIE have currently forecast lower allocations relative to other regions. If allocations in the Murrumbidgee do not increase, this will likely create pent-up demand for water in this region that cannot be fulfilled through trade since the Murrumbidgee is upstream of other regions and cannot import water.

The forecast prices are modelled estimates of the average annual price for 2022–23. In practice, prices are expected to fluctuate throughout the year around the modelled annual average price (Figure 7). ABARES has also produced a dashboard visualisation to accompany this report, which presents the price forecasts for each region in the sMDB.

Figure 7 Water allocation price scenarios, sMDB average, 2019–20 to 2022–23

Note: Water prices in 2020–21 dollars.

Production supported by water availability and low prices

Production of irrigated crops in 2022–23 is expected to be supported by high water availability (particularly at the beginning of the year) and low water prices. However, regional differences in water supply and prices within the sMDB will affect production forecasts for cotton and rice.

Cotton production is forecast to decrease in 2022–23 under all scenarios (following an exceptional year in 2021–22) largely driven by a forecast decrease in cotton prices (Table 2 ). An increase in forecast water prices in the NSW Murrumbidgee will also contribute to the decrease in forecast cotton production (and rice production), as most irrigated cotton in the sMDB is grown in the Murrumbidgee.

| Industry | 2021–22 modelled (tonnes) |

Extreme dry (tonnes) |

Dry (tonnes) |

Average (tonnes) |

Wet (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almonds | 118,595 | 126,694 | 126,694 | 126,694 | 126,694 |

| Cotton | 139,335 | 87,065 | 94,788 | 100,990 | 104,307 |

| Grapevines | 1,285,663 | 1,280,190 | 1,280,190 | 1,280,190 | 1,280,190 |

| Rice | 625,250 | 345,533 | 449,717 | 537,863 | 644,210 |

Source: ABARES, ABS, Cotton Australia and SunRice

Note: Modelled production in 2021–22 for cotton and rice is exogenous and incorporates the best available information. Rice production reported in paddy tonnes.

Almond production in 2022–23 is forecast to increase, as almond trees continue to mature and increase yields. Grapevine production is forecast to remain at a similar level to 2021–22.

Total gross value of irrigated agricultural production (GVIAP) in the sMDB is forecast to remain around $6 billion in 2022–23 in the average scenario. Although, there are some differences at the industry level.

Cotton GVIAP is forecast to decrease in 2022–23 in all scenarios, due to the current expected lower water allocations and consequently production in the Murrumbidgee where most of the cotton in the sMDB is grown. GVIAP for almonds is forecast to increase by 18% in 2022–23 due to both increased production and high almond prices.

| Industry | 2021–22 modelled ($m) |

Extreme dry ($m) |

Dry ($m) |

Average ($m) |

Wet ($m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almonds | 751 | 885 | 885 | 885 | 885 |

| Cotton | 497 | 257 | 279 | 298 | 307 |

| Dairy | 1,062 | 1,091 | 1,100 | 1,103 | 1,105 |

| Pastures for grazing and hay | 722 | 760 | 782 | 774 | 730 |

| Horticulture (incl. fruit & vegetables) | 1,625 | 1,649 | 1,649 | 1,649 | 1,649 |

| Grapevines | 714 | 657 | 657 | 657 | 657 |

| Rice | 302 | 160 | 209 | 250 | 299 |

| Other cereals and broadacre | 388 | 399 | 414 | 388 | 321 |

| Total | 6,061 | 5,857 | 5,975 | 6,002 | 5,953 |

Source: ABARES

Note: GVIAP estimates do not include nursery production and are therefore not comparable to ABS estimates. Values in 2020–21 dollars.

Outlook scenarios

ABARES designed four outlook scenarios for 2022–23 (Table A1). Outlook scenarios released by the states remain indicative only. Actual water allocations will depend on realised seasonal conditions. Outlook scenarios are also subject to updates throughout the year.

As shown in Table A1, the definition of outlook scenarios and the level of information provided varies by state water agency. The ABARES outlook scenarios are largely based on those used by the Northern Victoria Resource Manager (NVRM). Outlook scenarios from other states were matched against the ABARES scenario definitions.

| ABARES scenario | NVRM scenario | SA DEW scenario | NSW DPIE scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme dry In 99 years out of 100, inflows to storages exceed those experienced in this scenario. Rainfall is in the 1st percentile of historical levels. |

Extreme dry Inflow volumes to storages that are greater in 99 years out of 100. |

Exceptionally dry 99% likelihood that actual allocations will exceed allocation forecast |

Extreme 99 chances in 100 of exceeding the allocation forecast |

| Dry In 90 years out of 100, inflows to storages exceed those experienced in this scenario. Rainfall is in the 10th percentile of historical levels. |

Dry Inflow volumes to storages that are greater in 90 years out of 100. |

Very Dry 90% likelihood that actual allocations will exceed allocation forecast |

Very Dry 9 chances in 10 of exceeding the allocation forecast |

| Average In 50 years out of 100, inflows to storages exceed those experienced in this scenario. Rainfall is in the 50th percentile of historical levels. |

Average Inflow volumes to storages that are greater in 50 years out of 100. |

Average 50% likelihood that actual allocations will exceed allocation forecast |

Average 1 chance in 2 of exceeding the allocation forecast |

| Wet In 10 years out of 100, inflows to storages exceed those experienced in this scenario. Rainfall is in the 90th percentile of historical levels. |

Wet Inflow volumes to storages that are greater in 10 years out of 100. |

Wet 25% likelihood that actual allocations will exceed allocation forecast |

Wet NSW has not released a forecast for this scenario. ABARES assumption. |

Source: ABARES, NVRM, SA DEW and NSW DPIE

Note: Allocation forecasts made by NVRM are created using a model of historical inflow volumes, and the chance that actual inflows will be higher than those presented. The wet scenario defined by SA DEW uses a higher likelihood measure, meaning this is a drier scenario than the wet scenario used by ABARES and defined by NVRM.

The scenarios describe four potential outcomes for the volume of water available for irrigation use in the southern basin in 2022‑23. In each scenario, the aggregate demand for irrigation water is assumed to be the same as 2021–22 levels. Therefore, prices in each scenario are primarily influenced by seasonal conditions, the volume of water available (which is affected by allocations and carryover), rainfall (which affects crop watering requirements) and trade limits that restrict the flow of water between regions.

Murrumbidgee allocations could be 10% higher if certain conditions are met

When water physically spills from Murrumbidgee storages, NSW water managers must decide whether to spill or retain the inter-valley trade (IVT) balance (water owed to the NSW Murray). This decision is based on the difference in water availability between the NSW Murray and Murrumbidgee around the time of the physical water spill.

- A decision to spill the Murrumbidgee IVT balance is likely when Murrumbidgee allocations are significantly lower than NSW Murray allocations. What this means for irrigators is typically an increase in Murrumbidgee allocations for the year. Since allocations are already forecast to reach 100% for NSW Murray entitlements, an IVT spill is more likely and NSW has indicated that Murrumbidgee general security allocations could increase by 5-10% if this happens in 2022–23 (see NSW Murrumbidgee Valley water allocation statement: 15 February 2022).

- A decision to retain the Murrumbidgee IVT balance (despite a physical water spill from Murrumbidgee storages) is likely when Murrumbidgee allocations are similar or higher than NSW Murray allocations. This typically means spilling Murrumbidgee water and preventing a loss of water owed to NSW Murray irrigators.

Rainfall scenarios

Table A2 shows the amount of rainfall for 2021–22 and ABARES forecasts for 2022–23. Scenario forecasts for 2022–23 by region were calculated as a percentile of historical annual rainfall between 1990–91 and 2019–20.

| Industry | 2021–22 (mm) |

Extreme dry (mm) |

Dry (mm) |

Average (mm) |

Wet (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSW Murrumbidgee | 460.6 | 191.8 | 221.8 | 297.3 | 463.7 |

| NSW Murray Above | 375.9 | 191.9 | 220.3 | 296.0 | 443.4 |

| NSW Murray Below | 285.8 | 160.3 | 174.6 | 248.5 | 389.7 |

| NSW Lower Darling | 241.7 | 124.0 | 137.4 | 187.2 | 311.6 |

| VIC Murray Above | 635.5 | 261.6 | 347.8 | 467.0 | 642.3 |

| VIC Murray Below | 259.2 | 143.6 | 162.4 | 216.5 | 349.5 |

| VIC Goulburn–Broken | 424.4 | 238.9 | 265.8 | 357.9 | 527.3 |

| VIC Loddon–Campaspe | 422.4 | 233.1 | 267.5 | 360.9 | 511.3 |

| SA Murray | 205.2 | 145.6 | 168.1 | 214.1 | 324.0 |

Source: BOM

Carryover scenarios

Table A3 shows an estimate of the volume of water carried over into 2022–23 and ABARES forecasts for carryover in 2023–24. Carryover is modelled based on forecasts for rainfall, entitlements on issue and allocations, along with state-based carryover rules. Included in ABARES forecasts are modelled irrigator expectations around climate in 2022–23 (see Hughes et al. 2021 for more details).

| Industry | Carryover into 2023–24 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carryover into 2022–23 (ML) |

Extreme dry (ML) |

Dry (ML) |

Average (ML) |

Wet (ML) |

|

| NSW Murrumbidgee | 739,131 | 55,698 | 75,352 | 367,775 | 567,599 |

| Above the Barmah Choke | 709,244 | 359,742 | 353,505 | 491,200 | 702,395 |

| Below the Barmah Choke | 851,247 | 262,730 | 238,227 | 336,123 | 639,302 |

| Northern Victoria | 1,013,400 | 398,635 | 624,550 | 825,506 | 1,045,711 |

| Total | 3,313,022 | 1,076,804 | 1,291,633 | 2,020,604 | 2,955,007 |

Note: Scenario values are ABARES forecasts. Above the Barmah Choke comprises NSW and Victorian Murray regions above the Barmah Choke. Below the Barmah Choke comprises NSW and Victorian Murray regions below the Barmah Choke. No carryover is assumed for SA Murray. Northern Victoria comprises the Goulburn, Broken, Loddon and Campaspe.

Water allocation scenarios

Table A4 shows water allocation forecasts by entitlement type for 2022–23. While these forecasts mostly reflect the outlook scenarios released by state water agencies, ABARES has also made some additional assumptions:

- Victorian low reliability entitlements will receive no allocations in 2022–23.

- SA Class 3 entitlements are comparable to high reliability entitlements in Victoria and high security entitlements in NSW.

- SA Class 3 allocations are assumed to be 100% under all scenarios, based on historical trends. The allocation outlook for SA Class 3 entitlements will be released on 15 April 2022.

- For NSW regions, allocations in the wet scenario are assumed to be 25% greater than the average scenario because a forecast for the ABARES wet scenario was not provided by NSW.

- Victorian Murray above and below (the Barmah choke) will receive the same allocation percentage as each other. The same assumption is made for NSW Murray above and below regions.

| Region | Entitlement type | Extreme dry (%) |

Dry (%) |

Average (%) |

Wet (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSW Murray | General | 25 | 30 | 100 | 100 |

| NSW Murray | High | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NSW Lower Darling | General | 25 | 30 | 100 | 100 |

| NSW Lower Darling | High | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NSW Murrumbidgee | General | 15 | 26 | 48 | 73 |

| NSW Murrumbidgee | High | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| VIC Murray | High | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| VIC Goulburn | High | 67 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| VIC Campaspe | High | 58 | 80 | 100 | 100 |

| VIC Loddon | High | 67 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| VIC Broken | High | 0 | 41 | 100 | 100 |

| SA Murray | High | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: NSW DPIE, NVRM and ABARES

Note: Entitlement type refers to general and high security entitlements in NSW

Annual inter-valley trade limits

Table A5 shows the annual trade limits used by ABARES to approximate inter-valley trade (IVT) rules within the sMDB. Trade limits in the forecast year (2022–23) are assumed to be the same as 2021–22.

These limits are intended to reflect average annual limits on irrigation water trade, after adjusting for expected environmental transfers (as opposed to limits on accumulated IVT account balances). In practice, trade limits can vary across and within years depending on river operation decisions and changes in trading rules.

| Region | Import limit (ML) |

Export limit (ML) |

|---|---|---|

| NSW Murrumbidgee | 0 | 250,000 |

| Above the Barmah Choke | No limit | 0 |

| Below the Barmah Choke | No limit | No limit |

| Northern Victoria | 50,000 | 85,000 |

| NSW Lower Darling | 0 | 0 |

Source: ABARES, MDBA, NSW DPIE and NVRM

Note: Above the Barmah Choke comprises NSW and Victorian Murray regions above the Barmah Choke. Below the Barmah Choke comprises NSW and Victorian Murray regions below the Barmah Choke. Northern Victoria comprises the Goulburn, Broken, Loddon and Campaspe regions.

|

Term |

Definition |

|---|---|

| Allocation | Proportion of a water entitlement that can be taken from the river that year. |

| Barmah Choke | A narrow section of the Murray River that runs through the Barmah–Millewa Forest. The Barmah Choke is a major hydrological constraint in the sMDB that restricts the flow of the Murray River to around 7 GL per day. |

| BOM | Bureau of Meteorology |

| carryover | Water allocated to entitlements that is carried over into the next year. |

| CEWH | Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder |

| ENSO | El Niño–Southern Oscillation |

| entitlement | The right to receive up to a certain volume of water in a year. Only surface water entitlements were considered in this report. |

| IOD | Indian Ocean Dipole |

| IVT | Inter-valley trade |

| ML | Megalitre |

| Northern Victoria | Northern Victoria is specified in this report as the Goulburn, Broken, Loddon and Campaspe regions. Does not include the Victorian Murray region. |

| NSW DPIE | NSW Department of Planning and Environment |

| NVRM | Northern Victoria Resource Manager |

| reliability | Measure of the average volume of water allocated to a particular entitlement type. Provides an indication of the likelihood that an entitlement will receive 100% of its nominal volume by the end of the water year, with high reliability entitlements receiving allocations before low reliability entitlements. |

| SA DEW | SA Department for Environment and Water |

| security | See reliability. |

| sMDB | Southern Murray–Darling Basin |

ABARES 2022a, Agricultural Commodities: March quarter 2022, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

ABARES 2022b, Natural fibres: March quarter 2022, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

ABARES 2022c, Seasonal conditions: March quarter 2022, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

BOM 2022, Climate outlook, Bureau of Meteorology, Canberra, accessed 24 March 2022.

BOM 2021, Australian Water Market Report 2020–21, Bureau of Meteorology, Canberra.

Hughes, N, Gupta, M, Whittle, L & Westwood, T 2021, A model of spatial and inter-temporal water trade in the southern Murray–Darling Basin, ABARES, Canberra, February.

MDBA 2022, Basin storage report: 16 March 2022, Murray–Darling Basin Authority, Canberra.

NSW DPIE 2022, Water allocation statements: 15 February 2022, NSW Department of Planning and Environment.

NVRM 2022a, Outlook: 15 February 2022, Northern Victoria Resource Manager, Tatura, accessed 15 March 2022.

NVRM 2022b, Seasonal determination: 15 February 2022, Northern Victoria Resource Manager, Tatura, accessed 15 March 2022.

SA DEW 2021, Current and historical allocations, SA Department for Environment and Water, Adelaide, accessed 15 March 2022.

Watch ABARES video presentation

Watch this short presentation from ABARES Water Analyst Rhys Downham as he summarises the key findings from this report.

Video transcript: ABARES Water Market Outlook for April 2022 (DOCX 124 KB)

Watch the full ABARES Perspectives: Water Market Outlook April 2022 – Webinar

Video transcript: ABARES Perspectives: Water Market Outlook April 2022 – Webinar (DOCX 43 KB)

Download the report

Water Market Outlook: April 2022 (PDF 917 KB)

Water Market Outlook: April 2022 (DOCX 1.5 MB)

Previous reports

Water Market Outlook: August 2021

Water Market Outlook: March 2021

For access to other past water markets outlook reports, visit the ABARES publications library.