There are many widely documented and researched ways to improve farm productivity. The main ‘drivers’ of farm productivity are summarised below:

Innovation and technology adoption

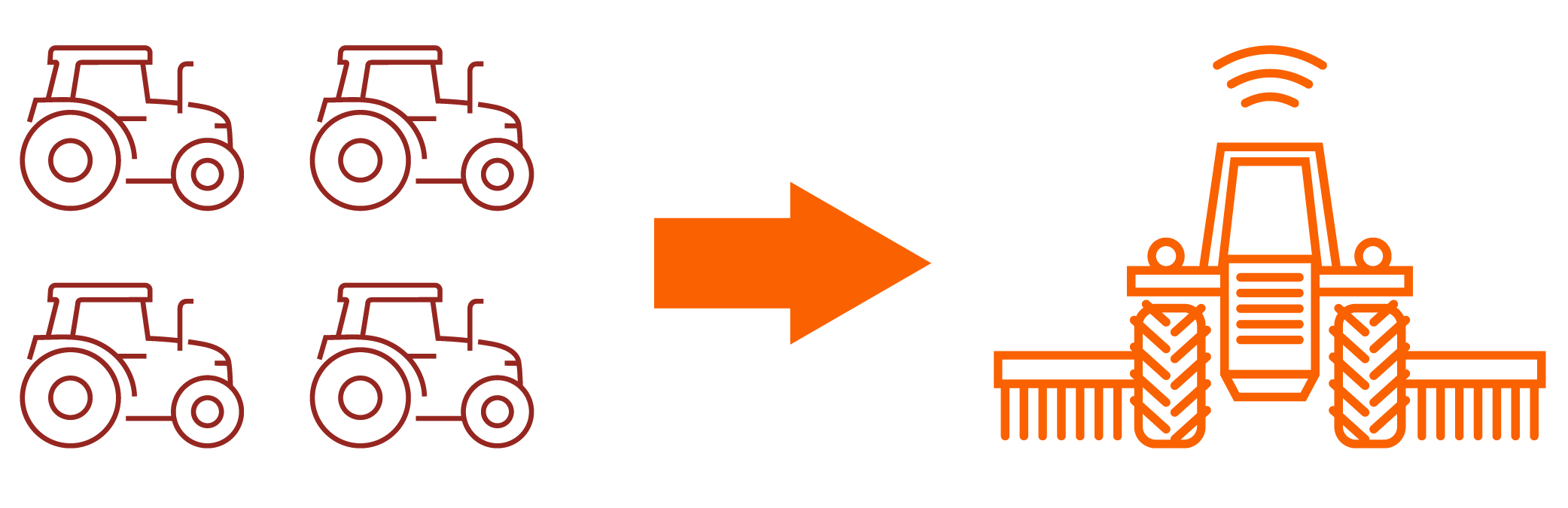

Innovation and the adoption of technology is closely linked to improvements in farm productivity and has generated significant gains for decades. It is a well‑proven way to reduce labour inputs, to minimise input waste (e.g., excessive chemicals, fertiliser, seed), and to maximise output (e.g., high yield crop varieties, improved livestock genetics). The hypothetical example below illustrates how innovation and technology adoption translate to farm productivity growth.

Alice, a crop farmer, decides to replace four old tractors with one new tractor. For the sake of illustration, let’s assume the new tractor is six times more powerful and efficient, and has built‑in precision ag technology. The total running cost of the new tractor is lower than the four old tractors combined, and its technology means that it can use inputs (such as seed and fertiliser) more efficiently while only requiring one operator rather than four.

This decision has two distinct impacts on the farm:

- The immediate impact is that the new machine increases the capital input of the farm and offers Alice the potential to produce more output with fewer other inputs (e.g., labour, fuel, seed, and fertiliser).

- In addition, Alice may also be able to benefit from the additional capability she has with the new tractor by making other business changes, such as employing fewer tractor operators or re-deploying these workers to other tasks; increasing farm size and benefitting from returns to scale, producing different crops and exploring new markets; increasing training and skills in precision agriculture; refining farming practices through analytical services such as yield mapping; and/or leasing the tractor and operator to other farmers.

Management skill and capacity

Managers require a broad range of knowledge and skills to maximise productivity. This can be expanded to include factors such as education, years and variety of experience, age, training, and health. The best farm managers are more likely to know how to optimise their business in uncertain price and seasonal conditions. They will have a comprehensive understanding of risk and reward, with an array of strategies at their disposal (e.g., capital hire, financial instruments). Strong managers will make use of all information available to fine tune their farm continuously.

Farm Size

Farm size has proven to be a core driver of productivity growth by spreading fixed costs such as management skill and machinery ownership, to generate more output. Many Australian broadacre farms have benefited from these increased ‘economies of scale’ by expanding their size. The average size of Australian broadacre farms has gradually increased over the last few decades, and the number of farms has decreased – reflecting structural change and the consolidation of farms.

The ‘farm size’ driver applies generally to farms restricted by their land area and there will be instances of highly productive small farms, as well as low productivity large farms. The size to productivity relationship continues to be debated in academic literature.

Research and development (R&D)

Research and development (R&D) investment is another key policy area that supports productivity. State and Commonwealth governments and universities invest substantial public funds in agricultural R&D each, alongside industry investment. Returns to public investment in R&D remain very high and warrant ongoing funding. ABARES research has found that for every $1 invested in agricultural R&D, there is an almost $8 return for farmers over 10 years. However, public investment in farm R&D has only increased gradually in recent years, particularly in comparison to private sector investment.

Public agricultural R&D tends to focus on long term discoveries, whereas the private sector focus is usually on the development of commercially viable shorter-term products — therefore private sector investment cannot simply replace public sector investment. A blend of both investment sources is needed. For example, precision agriculture draws on public sector developments in GPS and satellite mapping, which are integrated into a commercial product that can be adopted and used practically for farming.

Government policy

Enabling markets to operate freely has been a successful policy strategy for improving farm productivity growth for many years. For example, the removal of marketing and price supports during the 1980s and 1990s contributed to productivity growth in the broadacre and dairy industries. Past policy reforms have led to the amalgamation of farms, better risk management and changes in the mix of agricultural commodities produced. ABARES work shows that past reforms have encouraged the reallocation of resources from less efficient farms to more efficient ones. Australia already has one of the lowest levels of farm subsidies in the OECD and has been identified as having highly competitive farm businesses.

Policy makers can drive productivity by opposing any distortionary support mechanisms and facilitating free markets. There may also be opportunities for further policy driven structural change and farm consolidation.

The weather

Seasonal variation in temperature, rainfall, and other conditions has a significant influence on short term farm productivity. Productivity tends to fall in drought years, with many inputs expended (either unavoidably or by risk taking), and output reduced (lower crop yields due to low rainfall). During periods of high growing season rainfall, productivity increases suddenly as yields are maximised. These short-term productivity peaks and troughs are temporary. While the weather certainly impacts productivity, it should not necessarily be relied upon as a ‘driver’ of productivity.

Australian farmers manage seasonal variability by adjusting their production systems as circumstances change, and by adopting new technologies and management practices. Ongoing growth in Australia’s agricultural productivity over time indicates that farmers have become more resilient and are adapting to climate variability and the challenges it creates.