James Fell

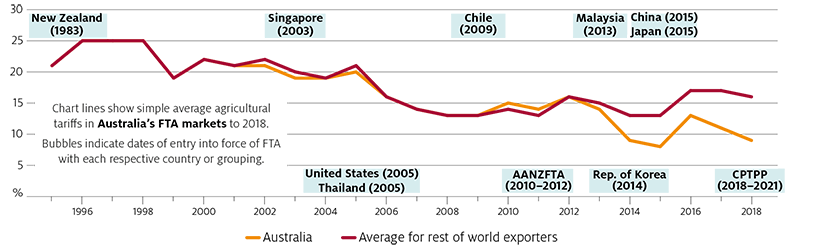

Australian agricultural exports have enjoyed lower tariffs in many export markets as a result of Australia’s free trade agreements (FTAs). These agreements bring a range of benefits, including better tariff and quota access for Australian exporters. But from the late 2010s, international competitors also started to enjoy similarly low tariffs through their own FTAs.

This is significant given the reliance of Australia’s agricultural sector on exports, with 70% of Australian agricultural production exported. This challenge to one aspect of Australia’s international competitiveness raises the importance of themes that are laid out in Delivering Ag2030, the Australian Government’s plan which sets the foundations for the agriculture sector to grow to $100 billion by 2030. To keep Australian agricultural exports competitive, it has become more important than ever to continue to reduce non-tariff measures, open up biosecurity export pathways, strengthen the multilateral trading system, address trade- and production-distorting agricultural subsidies, respond to changing societal concerns (including promoting and improving sustainability and emissions credentials) and advance productivity growth.

Australia’s first FTA, with New Zealand, entered into force in 1983, and Australia has since concluded 14 FTAs between 2003 and 2020. Three quarters of Australia’s agricultural trade in 2020–21 was destined for Australia’s FTA partners. These agreements bring a range of benefits, including lower tariffs, and provide more streamlined rules and procedures for Australian exporters to access key markets. FTAs also reduce barriers behind borders, encourage investment, improve trade rules, promote closer international relationships and offer protocols for resolving disputes.

Ultimately, this improved market access makes Australian agricultural goods more competitive to overseas buyers. The many benefits of Australia’s FTAs are outlined by Duver & Qin (2021).

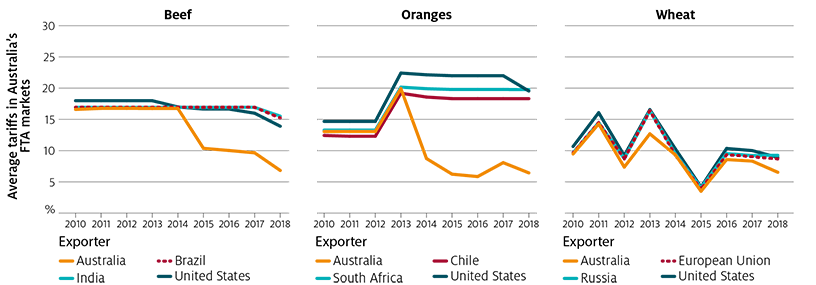

Australia enjoyed an early mover advantage over its international competitors in key markets, helping Australian exporters establish a presence in overseas markets. Average agricultural tariffs faced by Australia’s exporters were lower than those faced by key competitors in its FTA markets (Figure 1). This is particularly apparent for Australia’s top agricultural exports: beef, horticulture (using oranges as an example) and wheat (Figure 2). These tariff advantages can contribute to an increase in exports since lower tariffs decrease the price of the product in the export market, making it more attractive to consumers.

Note: all tariffs are converted and expressed as a percentage equivalent. Tariff data are for HS Chapters 01-24, excluding 03, and represent an approximation of the definition of agricultural goods in the WTO Agreement on Agriculture.

Source: ITC (2020), DFAT (2021), ABARES analysis

Source: ITC (2020), ABARES analysis

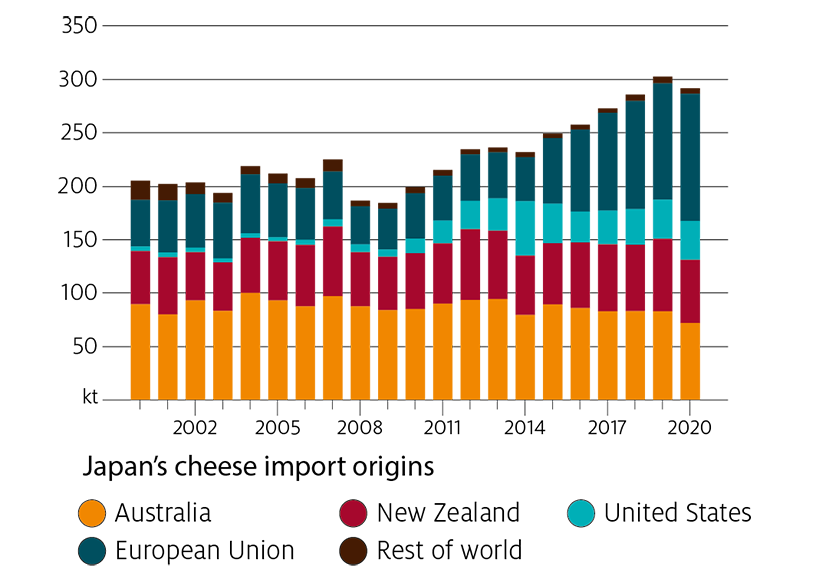

Sometimes the benefits of FTAs are not immediately obvious when an agreement does not result in significant reductions in tariffs. In some agreements, the agreed outcomes are sufficient to allow Australian exports to maintain their competitiveness in the partner market. This is evident in the case of Australian cheese exports to Japan. The negotiated outcomes for cheese in the Japan-Australia Economic Partnership Agreement (JAEPA), which entered into force in 2015, did not result in an increase in cheese exports. Between 2016 and 2020 a number of international competitors also achieved market access wins in Japan. However, Australia’s improved access to a larger quota with lower tariffs than the WTO’s most favoured nation tariff helped maintain the competitiveness of Australian cheese exports to

Japan (Figure 3, Duver & Qin 2021).

Source: UN Statistics Division (2021)

Source: Shutterstock.com

FTAs can bring first mover advantages but as other countries signed trade agreements with Australia’s FTA partners, Australia’s tariff advantages began to erode. This happened as competitor nations successfully negotiated tariffs, often equivalent to those negotiated by Australia. These ideas are best demonstrated through examples of some of Australia’s key agricultural exports.

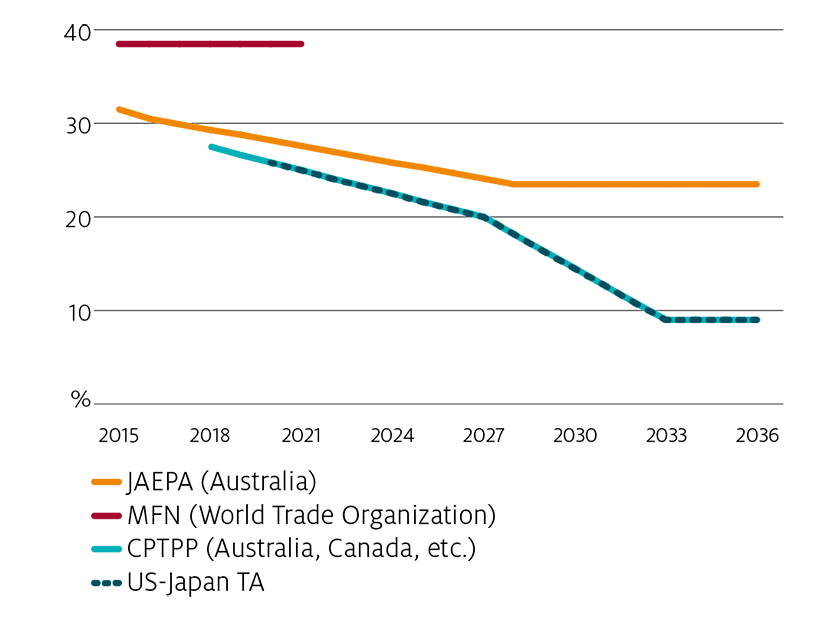

Beef to Japan

Beef is Australia’s top agricultural export, and one of Australia’s top export destinations for beef is Japan. When JAEPA entered into force, Australia gained a tariff advantage over its competitors, the United States, Canada and New Zealand (Figure 4). However, by the end of 2018 the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) came into force, which put Australia and Canada on an identical tariff footing in the Japanese market, with tariffs lower than JAEPA. The tariff advantage that Australia maintained over its largest competitor, the United States, was eroded in 2020, when the US-Japan Trade Agreement gave the United States the same tariff treatment as CPTPP. This was however half a decade after Australian exporters.

Note: for fresh or chilled beef. MFN Most favoured nation applied tariff is shown as ending at 2021 because future tariffs for those arrangements are unknown.

Source: Duver & Qin (2021)

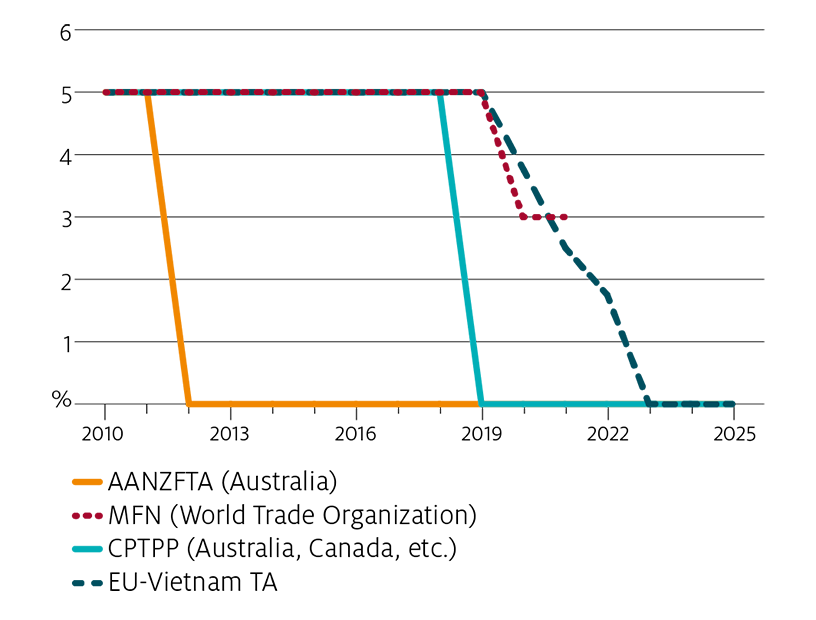

Wheat to Vietnam

Australian wheat exports benefitted from a tariff advantage in Vietnam for 7 years following Vietnam’s accession to the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement (AANZFTA). This was unmatched by other major wheat exporters in the market, Argentina, Canada, the European Union, Kazakhstan, Russia and the United States (Figure 5). In 2019, Vietnam acceded to CPTPP, providing Canadian wheat with the same tariff-free access as Australian wheat. Wheat from the European Union will be tariff-free by 2022 under the EU-Vietnam Trade Agreement.

Note: MFN Most favoured nation applied tariff is shown as ending at 2021 because future tariffs for those arrangements are unknown.

Source: DFAT (2021), ITC (2021)

The early advantage enjoyed by Australian exports provided the opportunity to establish a market presence for Australian agricultural goods ahead of international competitors. However, the examples above demonstrate that competitors are now chasing closely behind Australia in tariff cuts in key markets. In some cases, such as beef to Japan, Australia’s exports no longer enjoy tariff advantages over competitors. This pattern is unlikely to change as competitors catch up in our key markets.

This fall in tariff-related competitive advantages comes against a backdrop of ongoing resilience in a changing agricultural and trade landscape facing Australian agriculture. Competitiveness-related challenges and opportunities in Australian agriculture and trade are not new and have included, but are not limited to, movements in exchange rates, domestic market reform, trade disruption, growth in trade- and productiondistorting agricultural subsidies by Australia’s competitors, natural disasters and COVID-19. Over time, a changing climate has also had an adverse effect on agricultural productivity and profitability (Hughes & Gooday 2021) with changes in seasonal conditions over the period 2001 to 2020 (relative to 1950 to 2000) reducing annual average farm profits by 23%.

Left unchecked, the anticipated erosion of Australia’s competitiveness from third-party FTAs will have an adverse effect on Australian agricultural exports. By definition, tariffs can not be negotiated lower than zero, highlighting the need for alternative avenues to improve our trade advantage. This includes better biosecurity market access, reductions in unjustified non-tariff measures (NTMs) and reductions in costs of compliance for justified NTMs.

There are broader avenues through which competitiveness can be pursued too, not just through trade agreements. Outside the scope of FTAs, these include reductions in agricultural subsidies abroad, greater certainty and predictability in global trading rules, adaptation to a changing climate, promoting sustainability credentials of export goods (including carbon-intensity and land stewardship) and advancing domestic productivity. Domestic policy is also an important enabler of export competitiveness, since it can encourage exporting industries and farmers to improve productivity and invest in research and development that bring improved returns to Australian agriculture.

Trade in agricultural and food products usually requires biosecurity arrangements between countries (Figure 6). Without the biosecurity arrangements in place, no trade can occur. New or improved biosecurity market access helps Australian exporters reach premium markets and/or can enable lower costs of compliance. Lowering compliance costs can boost competitiveness in overseas markets. The importanc of market access, including biosecurity arrangements, for supporting export growth is explored in Hogan& Gunning Trant (2021). In the five years to 2019–20, 265 market access achievements were registered, including new, improved, restored and maintained access.

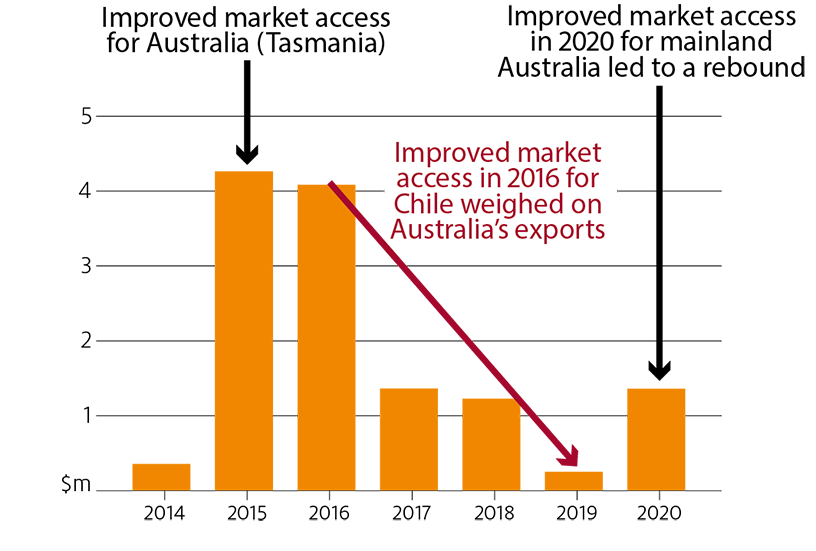

A demonstration of improved biosecurity arrangements is highlighted in the case of Australian cherries to the Republic of Korea (Figure 7). These improved arrangements were negotiated in 2015 and provided Tasmanian cherry exporters access to a premium market. Without these arrangements, the increase in Australian cherry exports to the Republic of Korea in 2015 would not have occurred. That trade was subsequently hampered by a rise in exports from Chile, a low-cost exporter, which had also gained market access to the Korean market. However, a further improvement to Australia’s biosecurity arrangements in 2020 allowed mainland cherries to be exported to Korea under a fumigation protocol, leading to a resurgence in exports.

Source: ABS (2021)

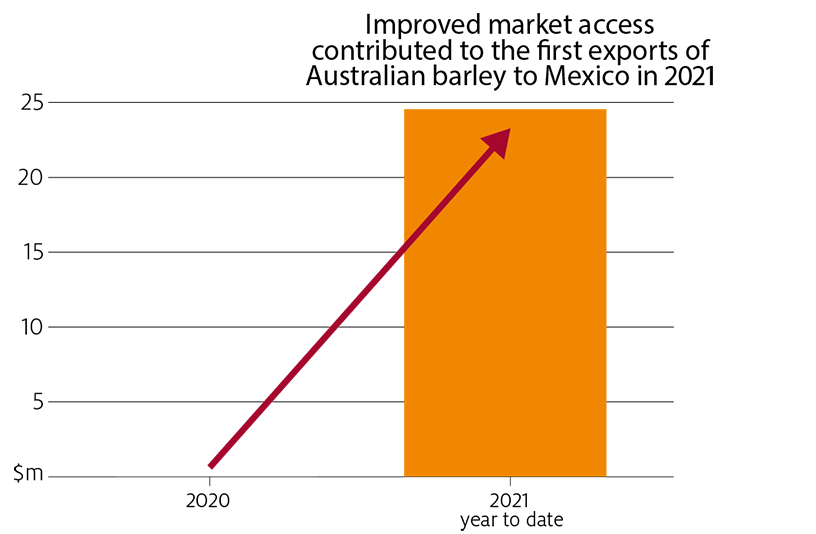

Another example of the benefits from improved biosecurity arrangements relates to Australia’s first barley exports to Mexico. Improved biosecurity arrangements opened a diversification opportunity for Australian exporters to ship barley to a new market. Following an agreement in 2020 that allowed in-transit phosphine fumigation, Australia’s barley exports to that market rose from zero in 2020 to $25 million in the first few months of 2021 (Figure 8).

Source: ABS (2021)

Source: Shutterstock.com

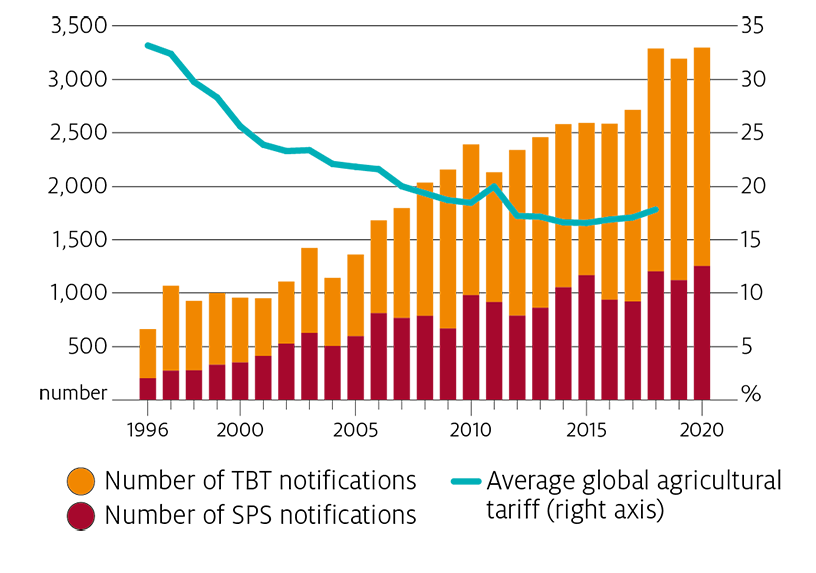

As global average tariffs in agriculture have fallen, the number of non-tariff measures (NTMs) notified to the WTO (across all goods) has risen (Figure 9). Reducing the impact of NTMs that are applied to Australian exports is important, particularly for measures that act as unjustified barriers to trade. NTMs generally raise compliance costs, so removing unjustified NTMs and reducing the cost of compliance with justified NTMs can help to improve export returns (Levantis & Fell, 2019).

Source: WTO (2021a, 2021b); ITC (2021); ABARES analysis

Around 99% of NTMs affecting agriculture are applied by importers non-discriminatorily on exporting countries. These are comprised principally of technical barriers to trade (TBTs) – which relate to technical regulations, standards and conformity assessment procedures – and sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures, which relate to human, animal and plant health. Most SPS measures are applied to agriculture and food. Many NTMs are applied legitimately to address, for example, human, animal or plant health concerns, and must be based on science. An NTM creates a barrier to trade when there is an unjustified compliance cost.

Hatfield-Dodds et al. (2021) highlight the “dance of giants”, as an emerging mega-trend in world markets. Shifts in power will reshape relationships, as global competitors pursue their economic interests. This means that Australian exporters could face risks and uncertainty, highlighting the importance of cementing and enhancing the global rules-based trading system. A potentially more contested global trading environment will require better multilateral rules and options for Australian exports to help navigate shifts that might occur.

To this end, moves to shore up certainty and predictability in the global trading system are important. This includes not only maintenance of global trading norms, but reform of WTO rules on trade and domestic support limiting or reducing the adverse effects of competitors’ agricultural subsidies.

As consumers become more empowered and social concerns change (Hatfield-Dodds et al., 2021), credentials demonstrating sustainability in agricultural production are an increasing area of international competitiveness. This includes carbon intensity in production systems and extends to the environmental benefits of stewardship of the land on which the exported product was produced.

Consistent with this need, Australia’s peak agricultural body is developing an Agricultural Sustainability Framework, providing consumers in Australia’s overseas markets with an assurance of the sustainability performance of Australia’s agricultural exports (NFF 2021). Australia’s Delivering Ag2030 framework sets out an ambitious aim for emissions reductions and outlines schemes for boosting environmental outcomes in Australian agriculture. Research and Development that translates into farmlevel sustainability improvements (such as reduced carbon-intensity) will continue to be important, similarly driving the necessary competitive edge for the future.

For most agricultural products, prices faced by Australian producers are set on international markets. This means that Australian farmers always need to produce an internationally competitive product to remain profitable. Ongoing innovation and change is explored further by Hatfield-Dodds et al. (2021) who explain the permanent race for advantage.

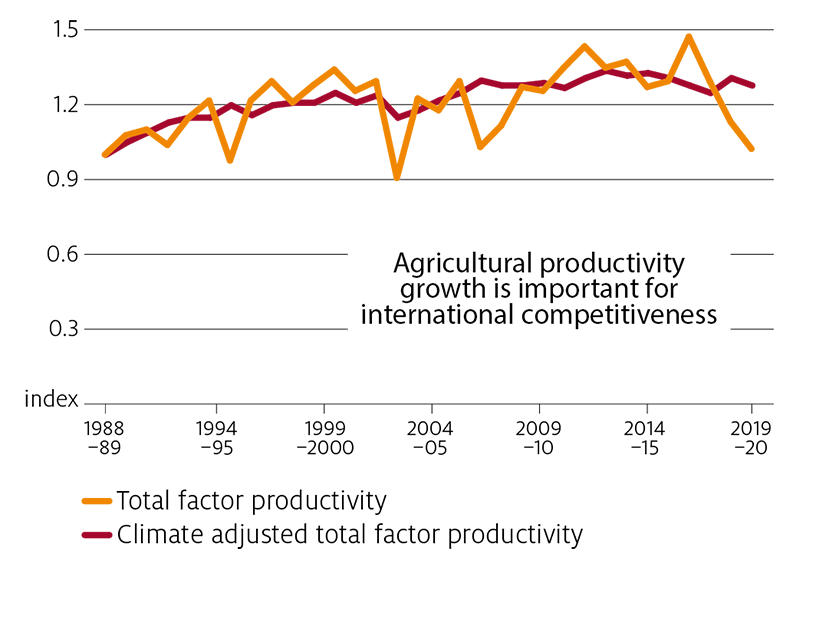

Productivity growth plays a crucial role in keeping Australian farmers and exporters competitive by reducing costs and/or improving returns. Similar to national market sector productivity, agricultural productivity growth has been increasing slowly on average over the past 30 years (Figure 10). In recent years the beneficial effects on productivity of structural change, changing farm management practices and adaptation to climate change have outweighed deteriorating seasonal conditions and less intense public investment in research and development (Zhao et al. 2021, Sheng et al. 2016).

Source: ABARES (2021)

It is important that productivity continues to rise to maintain international competitiveness. Previous drivers of productivity growth can act as a guide for what may drive productivity into the future. ABARES (2021) and Zhao et al. (2021) identify these as:

- microeconomic reforms, leading to structural change and changes in resource allocation (evidence of structural change can be seen in the growth in production shares held by large farms)

- investment in farm managers’ education and work experience

- R&D investment in technology

- on-farm adoption of technologies and changing management practice, which have together mitigated the negative impact of climate trends (Hughes et al. 2017).

Continued adaptation to a changing climate and production processes that are internationally competitive in emissions intensity will also be important for keeping Australian agriculture competitive on world markets. Australian farmers are already demonstrating evidence of such adaptation (Sheng et al. 2021; Hughes et al. 2017; Hochman et al. 2017). However, to restore Australian agricultural productivity growth to previous levels and to maintain international competitiveness, more is required. A path forward for productivity is suggested by Hughes& Gooday (2021) in a recent ABARES Insights report and by Delivering Ag2030, which provides a framework that includes deregulation, human capital, innovation and research, and land stewardship.

Source: Shutterstock.com

Improving international competitiveness is about more than just tariffs. Despite the gradual erosion of Australia’s tariff advantages in some markets, its international trade strategy continues to be successful and is delivering benefits for Australian agricultural producers (Duver & Qin 2021).

In line with Delivering Ag2030, Australia is advancing improvements to biosecurity market access in key markets, creating new access and working to maintain existing access, while safeguarding Australia from exotic pests and diseases. Likewise, through Delivering Ag2030, Australia is strengthening agricultural ties with export markets, delivering new trade and market access. An element of this will include reducing unjustified NTMs and reducing cost of compliance with justified NTMs to keep global trade moving. Australia is also pursuing reform of WTO rules on trade and production-distorting domestic support to limit (or reverse) growth in competitors’ agricultural subsidies. Progressing these contributions to Australia’s international competitiveness is supported by the work of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry’s overseas network, in partnership with industry.

On the domestic front, productivity growth remains ever important. Australian farmers have adapted to challenges over time, including trade disruptions, natural disasters, COVID-19 and a changing climate, by changing on-farm practices and using technology to find ways to offset the negative impact on productivity. Sustainability, including carbon intensity, will become ever more prominent consumer concerns. Australian producers will need to respond and adapt production to remain internationally competitive. It is through these initiatives and investments, both private and public, that Australian agriculture will maintain its international competitiveness over the long term.

ABARES 2021, Australian Agricultural Productivity Australian Agricultural Productivity - Department of Agriculture.

ABS 2021, International Trade, Australia: July 2021 [unpublished data], cat. no. 5465.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

DFAT 2021, Free Trade Agreement Portal, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra, accessed 1 September 2021.

Duver, A & Qin, C 2021, Free trade, competitiveness and a global world: How trade agreements are shaping agriculture, ABARES Insights, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

Hatfield-Dodds, S, Hajkowicz, S, & Eady S 2021, Stocktake of megatrends shaping Australian agriculture: 2021 update, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resources Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

Hochman, Z, Gobbett, D & Horan, H 2017, Climate trends account for stalled wheat yields in Australia since 1990, Global change biology, 23 (5).

Hogan, L & Gunning-Trant C 2021, Australia’s biosecurity market access and agricultural exports, ABARES research report 21.07, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Canberra.

Hughes, N & Gooday, P 2021, Climate change impacts and adaption on Australian farms, ABARES Insights, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

Hughes, N, Lawson, K & Valle, H 2017, Farm performance and climate: Climate-adjusted productivity for broadacre cropping farms, ABARES research report 17.4, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

ITC 2021, Market Access Map, International Trade Centre, Geneva, accessed 1 April 2021.

Levantis, G & Fell, J 2019, Non-tariff measures affecting Australian agriculture, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Canberra, accessed 18 Nov 2021.

NFF 2021, 2021 Report Card, National Farmers Federation, Canberra.

Sheng, Y, Mullen, J & Zhao, S 2016, Has Growth in Productivity in Australian Broadacre Agriculture Slowed? A Historical View, Annals of Agricultural & Crop Sciences, 1 (3).

Sheng, Y, Zhao, S, Yang, Y 2021, Weather shocks, adaptation and agricultural TFP: a cross-region comparison of Australian broadacre farms, Energy Economics, 101 (1), 1-14.

UN Statistics Division 2021, UN Comtrade, United Nations Statistics Division, New York, accessed 1 September 2021.

WTO 2021a, Sanitary and Phytosanitary Information Management System, World Trade Organization, Geneva, accessed 12 August 2021.

——2021b, Technical Barriers to Trade Information Management System, World Trade Organization, Geneva, accessed 12 August 2021.

Zhao, S, Chancellor, W, Jackson, T & Boult, C 2021, Productivity as a measure of performance: ABARES perspective, Farm Policy Journal, Autumn 2021, Australian Farm Institute, Sydney.

Download the report

ABARES Insights: Analysis of Australia’s future agricultural trade advantage – PDF