Authors: Nyree Stenekes, Rob Kancans, Bill Binks

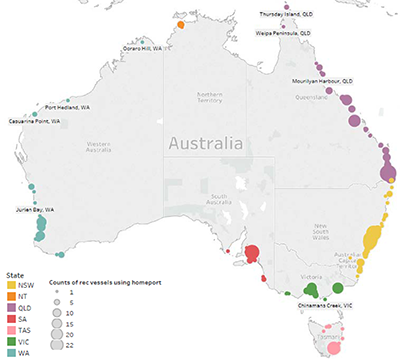

Source: ABARES domestic boater survey, 2017.

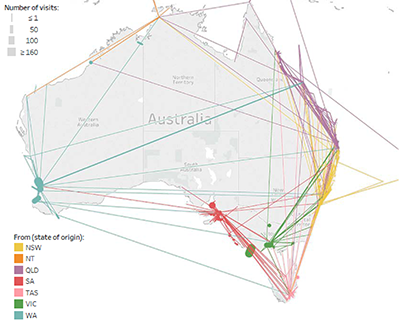

Source: ABARES domestic boater survey, 2017.

Background

This report presents key results from a national survey of 1,585 recreational boat owners, co-owners or crew (operators) about their boat maintenance practices.

The purpose was to inform a national communication approach to reducing the risk of marine pest translocation via biofouling of recreational boats in the Australian marine environment.

The focus of the survey was on the biofouling management actions of people who own vessels, such as yachts (keel boats) and motor cruisers that are usually kept in the water where conditions may encourage the growth of invasive marine plants and animals.

Access to jurisdictional recreational boat licence and registration databases, to develop a national sample frame of recreational boat owners, was unavailable.

Therefore, a non-probability sampling approach was employed to recruit participants from this hard-to-reach population. A number of approaches were used to recruit participants, such as through informal social networks of people with connections to recreational boat owners through their day-to-day work activities; industry associations; managers of marinas; boat and yacht clubs; traditional media advertising; and social media.

Data was captured via an online survey platform that was open between February and July 2017.

The results of the survey are not statistically representative of the recreational boat population, however, response to the survey showed there was adequate coverage across a number of relevant strata:

- both sailing boats and powerboats

- the majority of boats between 5 and 24 metres in length

- storage location of boats at marinas or swing moorings

- responses across all states and territories in Australia proportional to registered owner numbers.

Key findings

- There was a high level of awareness of marine pest risk among Australian recreational boaters who participated in the survey. Almost all respondents (95 per cent) were aware that marine pests can be present as biofouling on their boat. And the vast majority (86 per cent) were aware that all boats can transfer marine pests if they have biofouling on them. Members of boating clubs or associations were more likely to be aware that all boats can transfer marine pests if they have biofouling on them.

- Self-assessed familiarity with the contents of key National Biofouling Management Guidelines for Recreational Vessels (Australian Government 2009) and the national Anti-Fouling and In-water Cleaning Guidelines (Australian Government 2015) produced by the Australian Government was quite low nationally (with about 20 per cent of survey respondents familiar).

- However, there were differences in the levels of familiarity with the National Biofouling Management Guidelines for Recreational Vessels by state. Familiarity levels among recreational boat operators with home ports in New South Wales (16 per cent) was lower than expected while more respondents with home ports in Tasmania (36 per cent) were familiar with the guidelines than expected. There was no significant difference in levels of familiarity with the national Anti-Fouling and In-water Cleaning Guidelines across the states.

- Domestic recreational boat operators who participated in the survey, undertake a range of biofouling management actions on a regular basis. The majority—around 60 per cent or more—of respondents nationally were doing many of the best practices, including: regularly cleaning the boat hull, cleaning the niche areas of the boat, renewing the anti-fouling coating each year and capturing the biofouling waste after cleaning. However, only about a third were cleaning the boat before moving it to another location.

- A large majority (>80 per cent) of respondents were interested in engaging in several of the practices more in future, including out-of-water hull cleaning, niche area cleaning, and maintaining the renewal of the anti-fouling coating at the current level. Most (66 per cent) said they would be likely to capture and dispose of biofouling waste in the future. There were, however, fewer respondents (42 per cent) willing to do regular in-water cleaning in the future, mainly due to concerns about release of contaminants and marine pests into waters and safety concerns. Only 35 per cent of domestic boat operators said they would be likely to clean the boat before moving it to another location in the future, mainly due to the cost of slipping, lack of care about boat performance, time taken for cleaning, cleaning not needed (i.e. if the boat was already clean, owners believed anti-fouling still operating effectively) or it was impractical to clean the boat in the water.

- A Community Based Social Marketing (CBSM) approach developed by McKenzie-Mohr (2011) was used in this project to identify which biofouling management actions were worth promoting in future public engagement or education campaigns. This approach has been applied in Australia to managing a range of invasive species, such as wild dogs and feral cats, and works especially well where managing risks successfully relies on actions taken by individuals in the community (Hine et al. 2015; McLeod 2016; Please et al. 2017).

- We identified and prioritised a number of key biofouling management practices that domestic recreational boat owners could engage in, which are regarded as important for minimising the translocation of marine pests. The behaviours (or management actions) were based on a review of the national and international guidelines relating to anti-fouling, cleaning and biofouling management for the recreational vessel sector (Australian Government 2009; 2015; International Maritime Organization 2012).

- An expert elicitation approach was used to rank the biofouling management actions according to their effectiveness in preventing the translocation of marine pests if undertaken regularly by the vast majority of recreational vessel owners. The following rankings emerged from the experts (in order from most to least effective):

- cleaning the boat before moving it to another location,

- renewal of anti-fouling coating,

- capture and disposal of biofouling waste after cleaning,

- cleaning niches areas,

- taking the hull out of the water for cleaning, and

- in-water hull cleaning.

- This process allowed the researchers to prioritise behavioural questions for inclusion in the recreational boater survey. Recreational boat operators responded to the national survey and gave their ratings on how regularly they did these actions, and how likely in future they would be to do these management actions.

- The rankings of experts were compared with those given by recreational boat operators who participated in the survey in a behaviour prioritisation matrix. The matrix produced an overall ranking of the biofouling management actions in terms of projected impact. The selector matrix helps choose the behaviours that have a combination of: a high degree of effectiveness in addressing the issue, a high probability that domestic boaters will adopt the behaviour, and are currently not widely being undertaken by domestic boaters.

- This process showed that the greatest overall benefits for marine pest management would arise from promoting behaviours in the following order:

- cleaning the boat before moving it to another location (i.e. clean-and-go)

- anti-fouling coating applied to the boat hull including the niche areas

- biofouling waste captured and disposed of after cleaning the boat.

- Although the experts ranked ‘clean-and-go’ as the most highly effective action, it was not commonly practiced by recreational boat operators (usually or always done by only 27 per cent). There were a number of reasons why domestic boat operators are not cleaning their boats before moving them, including: clean before you go was not applicable because they were not moving the boat far, or it was already clean, or it was not practical (boat is stopping for short periods while in transit), and the high cost of using a slipway if the cleaning requires dry docking or hauling out. External factors they mentioned were the difficulty in accessing a local slipway, particularly one which has the required facilities (for example, able to haul out larger boats), and access to safe areas that were free of sharks or crocodiles for in-water cleaning. These factors are likely to mean that there will be limited adoption of ‘clean-and-go’ without significant changes to the opportunities available for domestic boaters to clean their boats before going.

- Renewing the ‘anti-fouling coating on the hull and niche areas’ of the boat regularly (at least once a year) was ranked by the experts as a highly effective action in reducing biofouling growth and the potential spread of marine pests if done properly. This is widely adopted—by 59 per cent of survey respondents—but some effort is needed to promote this action further. Anti-fouling renewal and a number of the other recommended actions were often done as part of the annual haul out and servicing of recreational vessels during the ‘off season’. It is therefore worth considering ways of encouraging domestic boaters to keep maintaining this action.

- ‘Waste capture and disposal’ of biofouling after cleaning the boat was rated as quite an effective behaviour by experts in reducing the risk of translocation of marine pests. Particularly if the fouling occurred in a port known (or suspected) to have marine pests and the waste capture was done in another (clean) port. But, the penetration of this behaviour into the recreational boat sector was moderate, with most (64 per cent) of the respondents who knew what happened to the waste, reporting that the biofouling waste was usually or always captured and disposed of properly after cleaning the boat. Thirty six per cent admitted that the biofouling waste is not regularly captured (sometimes, rarely or never). A group of 142 further respondents said they didn’t know if it was captured and disposed of, in the main because someone else does it for them. There was considerable willingness to engage further in biofouling waste capture in the future (66 per cent of those who answered this question). This suggests there are opportunities to encourage this practice, such as by providing better access to facilities that have waste capture and motivating people to do so, for example, by explaining more clearly the circumstances in which waste capture is recommended and why.

- The other actions that related to regular cleaning of the boat hull out of the water and cleaning of the niche areas are quite effective actions with a moderate to high degree of penetration in the domestic recreational boating sector, and relatively high levels of willingness to adopt these actions in future. This suggests that there is a high level of motivation present among recreational boat operators who can see the benefits of regular cleaning and maintenance. These actions are often part of the yearly anti-fouling, maintenance and repair schedule and ensures that the operation of the boat is reliable and safe. There was a high level of willingness to continue hauling out the boat for cleaning and maintenance once a year. The most commonly reported barrier to continuing this was the high costs of slipping and hauling out, the availability and accessibility of those facilities and the time consuming nature of the procedure.

- ‘Cleaning the boat hull in the water’ was rated on average by experts as a less effective behaviour for preventing translocation of marine pests. The penetration of the behaviour into the recreational boat sector was moderate, with 60 per cent of survey respondents cleaning their boat hulls in the water at least once a year or more often. However, the probability of recreational boat operators more widely adopting in-water cleaning in the future was low with a majority (58 per cent) of survey respondents saying they were unlikely to have their boat hulls cleaned in the water in the future. A common reason given was the potential release of contaminants into marine waters, in the context of government guidelines discouraging removal of hard growth in the water. ‘Cleaning the hull in water’ had the lowest effectiveness score and low continued adoption score which were the significant factors in the low overall impact rank for this management practice.

To identify groups for further focus, we investigated recreational boat operators’ level of adoption of key biofouling practices in more detail using a cluster analysis technique. This enabled us to identify homogenous groups of survey respondents who shared similar biofouling management practices.

- Three cluster groups emerged from the cluster analysis, who can be described as the ‘Minimalists—DIY group’, those with a ‘Comprehensive regime—active club members’, and the ‘OK—but could improve’ group.

- The ‘Minimalists—DIY group’ represented 43 per cent of survey respondents. This group had a minimalist biofouling management regime, characterised by a very low proportion undertaking all the key biofouling management actions. Most (59 per cent) were doing the anti-fouling renewal themselves rather than using a service provider. This group were less likely to be a member of a boating club or association, and their boats were kept in water for longer periods over the year (average 91 days) than the other groups. Most (59 per cent) had travelled outside their home port or harbour in the last 12 months. The infrequent nature of cleaning and anti-fouling suggests that this group represents a high risk for biofouling growth and domestic marine pest translocation.

- ‘Comprehensive regime—active club members’ were the smallest group of domestic boaters representing 19 per cent of respondents. This group were typically going above and beyond the requirements of the voluntary national guidelines in terms of biofouling management. Very little effort is needed to maintain their biofouling management regime as they are motivated not by biosecurity concerns, but by boat efficiency and performance, particularly for better cruising and racing experiences. Frequent cleaning and biofouling actions among this group suggests the boats in the group pose a relatively low risk of developing biofouling growth and thus a lower risk of domestic marine pest translocation.

- This left 38 per cent of survey respondents in the ‘OK, but could improve’ group. This group of domestic boaters were managing some biofouling actions—for example, almost all were renewing the anti-fouling coating on the boat once a year, and cleaning the boat thoroughly out of the water once a year or more often. But a large proportion were not engaging regularly in a number of other management actions, such as 39 per cent were never doing in-water cleaning, and only 25 per cent were usually or always cleaning the boat before moving it to another location.

- This suggests there is some confusion among domestic recreational boaters about whether in-water cleaning is a good biofouling management practice, and if it is, under which circumstances. A sizable proportion in cluster group 3 (‘OK but could improve’), for example, were ‘Never’ or not very regularly doing in-water cleaning (39 per cent). Some of the reasons reported for never cleaning the boat in the water were legitimate, such as it is not permitted in many marinas, it is illegal in some states, because of the potential for release of chemicals or pollution, or because of the risk of spreading of marine pests in the environment, or the boat does not need it/or it is not appropriate due to the type of anti-fouling paint used. It may be worth looking at the messaging around this practice with a view to being more specific about when in-water cleaning is desirable and should be encouraged (such as only for cleaning the slime layer; no scraping of hard growth).

- There is a considerable interest among a large proportion of recreational boat operators in ‘doing the right thing’ and ‘protecting the environment’, as is demonstrated by comments about the benefits of undertaking biofouling management actions. The analysis above presents opportunities to develop messaging that could be used as part of future engagement strategies with recreational boaters to influence behaviour voluntarily and promote best practice biofouling management activities. The messages could be tailored further to suit particular groups of recreational boat operators such as the three cluster groups, so that they are appropriate. Engagement tactics and messaging would need to be tested with recreational boat operators and developed further in the context of a broader education or outreach campaign.

- The most popular information sources for recreational boat operators for advice and information about boat anti-fouling and hull maintenance were industry service providers (e.g. marinas and slipways) (68 per cent of respondents are using this source), the Internet (e.g. boating blogs, Facebook) (52 per cent) and other boat owners (46 per cent). Yacht and boat clubs were an important source of information used by 28 per cent of respondents.

- There were some differences within the domestic boater cohort. Respondents with sailing boats were more likely to be using the Internet (e.g. boating blogs, Facebook), yacht or boat clubs, and other boat owners to get information about anti-fouling and hull maintenance than were powerboat operators. Those who were members of a boating association or club were more likely to get information from pamphlets/brochures, from yacht or boat clubs, and other boat owners, than respondents who were not members of an association or club.

- Recreational boat operators with home ports in New South Wales were more likely than expected to use industry service providers such as marinas and slipways (81 per cent) as information sources than were survey respondents in other jurisdictions. Recreational boat operators with home ports in Victoria were more likely to be using other boat owners and yacht or boat clubs as information sources than expected, compared to survey respondents in other jurisdictions.

Recreational boat operators' self-management of biofouling in Australia (PDF 3.0 MB)

Recreational boat operators' self-management of biofouling in Australia (DOCX 2.45 MB)

If you have difficulty accessing these files, visit web accessibility for assistance.

This dashboard ABARES recreational boater survey results 2017 | Tableau Public presents results of a survey of 1,585 recreational boat operators in 2017 about boat biofouling management and patterns of vessel use.