Jonathan Wong, Charley Xia, Harry Coë and Charlie Qin

Key points

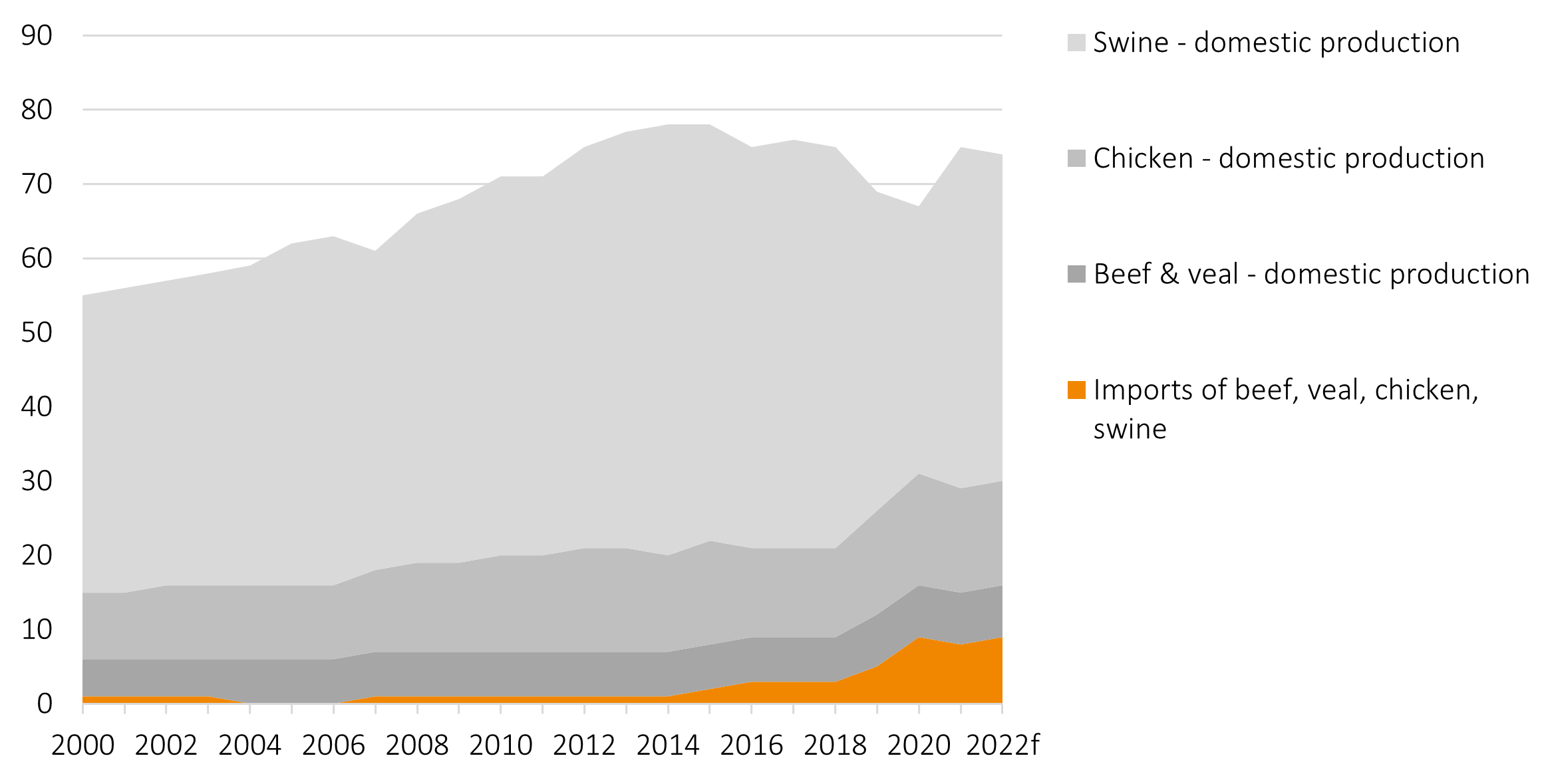

- China’s demand for meat has increased faster than its domestic production.

- This has resulted in China increasing its meat imports.

- This trend is expected to continue through the medium term.

China’s meat import demand profile has changed over the last decade and is expected to continue through the years ahead. Increases in beef and sheepmeat demand have been driven by income growth. More recent increases have been driven by changes in the relative prices of other meats, notably, pork. Demand increases have outpaced China’s domestic beef and sheepmeat production. This is likely to continue in the medium term with imports continuing to play a significant role in meeting the difference between demand and domestic supply. The country’s meat demand profile has changed under China’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, with these trends expected to continue in the medium term.

Mobility restrictions in China related to COVID-19 are likely to have reduced demand for meat in China, particularly meat consumed through food services. Nonetheless, medium- to long -term changes in China’s demand profile are likely to continue in the coming years.

Long term income growth has increased and diversified Chinese protein consumption

In the two decades to 2020, rapid expansion of China’s economy from industrialisation and urbanisation has contributed to a sharp increase in the income of its households. The share of household budgets spent on food during this period has fallen. With higher incomes and more disposable income, many Chinese consumers have changed their food consumption patterns to incorporate greater protein consumption. This has been supported internally by greater policy focus on ensuring food security and reliable, high-quality supplies of diversified proteins. More information on these trends can be found in What China wants.

Consumer choices in the medium term affected by price changes between alternatives

From 2018 to 2020, Chinese consumers appear to have substituted from pork to other proteins, including beef and sheepmeat, due to relative price differences (Figure 1.1). Pork became relatively more expensive due to the impacts of African swine fever (ASF), which reduced the number of pigs available for pork production. However, even as pork became relatively cheaper in 2021, China’s beef consumption was still higher in absolute terms than in 2020. This suggests that Chinese consumer preferences for beef and sheepmeat have increased.

Figure 1.1 Relative Chinese meat prices and consumption, January 2011 to November 2021

Safety and quality becoming more important to consumers

In addition to income and relative prices driving overall demand, China’s recent 5-year livestock plan notes that Chinese consumers are becoming more conscious of product safety and quality. The change in consumer awareness has contributed to a shift in consumer demand towards sources that reflect these attributes and have greater traceability, such as large domestic enterprises or imports from reputable markets. This has provided opportunities for countries that can demonstrate their ability to meet those requirements, such as Australia.

In its recent 5-year plan for the livestock sector, China plans to increase its meat production through policies designed to modernise and stabilise production of its domestic livestock industries including pork, beef, mutton, poultry, and dairy. These plans include stabilising supply through scaling-up farms, improving breeding genetics, better disease prevention, and developing farm-industry links for internalising the environmental costs of production. Chinese policymakers are calling for a combination of innovation and market forces to use inputs, including land, more efficiently to meet these goals. However, there are other factors that its livestock industries will need to navigate through to 2025.

Falling profitability has placed pressure on producers

China’s pig herd numbers have recovered to their pre-ASF levels. Pork supply is plentiful, which has resulted in low pork prices. However, low pork prices and high feed costs are putting financial pressure on pig producers. Figure 1.2 shows the pork to corn and soy price ratios are cyclical. Profitability was likely to have been higher for those that could produce pork during the ASF outbreak, but it is now lower than pre-ASF outbreak. The Chinese government is undertaking programs to improve profitability for livestock producers during these downturns.

Figure 1.2 Pork to feed price ratios, March 2003 to March 2022

Concerns for environmental footprint and disease pressures

Greater intensive livestock production operations can impose environmental costs and biosecurity risks. These have been increasingly factored into the social impact of livestock production in China. Chinese consumers and policymakers have also raised concerns for the environment, food safety and disease prevention as priorities. In September 2021, the Chinese government released its 14th Five-Year National Agriculture Green Development Plan. It identified resource protection, pollution control, restoration of agricultural ecology, and the development of low-carbon agricultural industrial chains as key goals to be achieved between the years 2021 to 2025. This could lead to further regulation and compliance costs on intensive livestock industries.

China’s recent 5-year plan for the livestock sector marked greater recognition of the importance of trade in meeting the quality and quantity of food demand — China’s meat imports have steadily increased over the last decade (Figure 1.3). The plan sets production targets to be 95% self-sufficient in pork production and 85% self-sufficient in beef and sheepmeat production, with imports to meet the rest of demand. However, this changed with the release of the Number 1 policy document in February this year, which removed the reference to imports and emphasises self-sufficiency. Given the magnitude of imports over recent years, China is expected to continue to be an active importer in both world meat and feed markets until its domestic production targets are met.

Figure 1.3 China meat supplies, 2000-2022

Source: US Department of Agriculture