Authors: Andrew Cameron

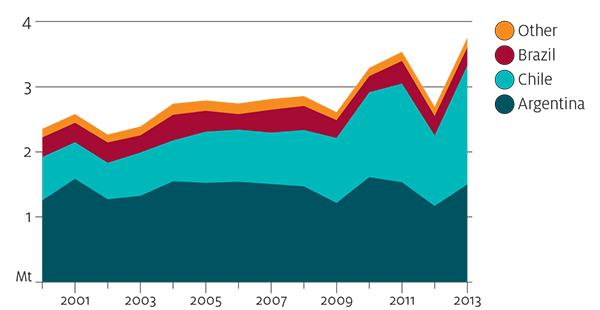

South America is a major world producer and exporter of wine. It accounted for almost 14 per cent of wine produced globally in 2013, up from 8 per cent in 2000. Chile and Argentina together account for over 80 per cent of South American wine production, and Brazil accounts for about 10 per cent (Figure 1).

This article focuses on Chile and Argentina, which are both major competitors in Australia’s export markets. Significant investment in the wine industries of both countries has led to improved wine quality, which has supported the expansion of exports of high-value, high-quality wine into many of Australia’s major wine markets.

Source: FAO 2016

Argentina

[expand all]

Domestic market

Argentina’s wine industry accounts for about 5 per cent of global production. In 2013 it produced 1.5 million tonnes of wine, making it the world’s seventh-largest producing nation by volume. The largest wine producers were France, Italy and the United States (FAO 2016). Australia is ranked eighth.

Most of Argentina’s wine grapes are grown along a 7 500-kilometre strip on the western edge of the country at the base of the Andes mountains (USDA–FAS 2015a).

Vineyards are protected from pests and diseases by the region’s high altitude and low humidity. This lowers Argentina’s production costs compared with other countries.

The main varieties of red wine produced in Argentina are malbec, bonarda and cabernet sauvignon, and the main white varieties are torrontés and chardonnay.

Argentina’s annual wine production was relatively unchanged from 2000 to 2013, averaging around 1.4 million tonnes, but the average quality has improved markedly.

Increased openness to international trade and investment since the 1990s allowed the adoption of more advanced production technologies, which supported the alignment of Argentina’s wine industry with international standards. For example, stainless steel fermentation tanks replaced wooden vats—which were difficult to keep clean and often released undesirable flavours into the wine (Farinelli 2013).

Access to export markets encouraged wineries to develop high-quality and distinctive varieties such as malbec, which is known as Argentina’s signature wine. Because of these improvements, the value of Argentina’s wine exports increased nearly 300 per cent in constant dollar terms between 2000 and 2015, peaking in 2012 at US$968 million (in 2016 US dollars).

Since 2012 the Argentine wine industry has been affected by high inflation, an overvalued currency, and government interventions in trade and foreign investment. Foreign investment by international wine conglomerates was vital for many of Argentina’s most successful export brands (Veseth 2010). However, in late 2011 the Argentine Government passed a law restricting foreign ownership of agricultural land. In 2012 the government introduced further restrictions in the form of increased import duties on a range of goods in an effort to maintain a trade surplus.

Equipment vital to the winemaking process, such as corks and staves, was subject to these duties so this raised input costs for Argentine winemakers (USDA–FAS 2015a).

At the same time, high inflation put downward pressure on domestic demand and an overvalued currency reduced export competitiveness (Williamson 2016). By 2015 wine exports were down 15 per cent in value terms and 12 per cent in volume terms from the 2012 peak.

Exports

Argentina exported 270 million litres of wine valued at US$818 million in 2015 (UN Statistics Division 2016). Most exports were comprised of bottled still wine (189 million litres), followed by bulk wine (77 million litres) and sparkling wine (4 million litres).

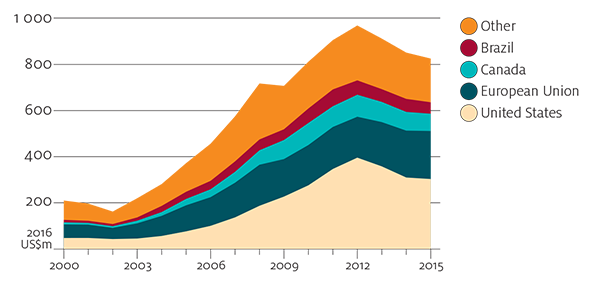

Argentina’s most important export market is the United States, which accounted for 37 per cent of exports by value in 2015 (down from a peak of 41 per cent in 2012) (Figure 2). The European Union was the next largest market, accounting for 25 per cent of exports, followed by Canada with 9 per cent. Brazil is the most important South American market, with about 6 per cent of Argentina’s export share by value.

The United Kingdom is an important and growing part of the European Union market, accounting for 10 per cent of Argentina’s wine exports in 2015. China is a relatively minor but growing market, accounting for 2.5 per cent of exports (worth US$21 million) in 2015, compared with 0.3 per cent a decade earlier.

Source: UN Statistics Division 2016

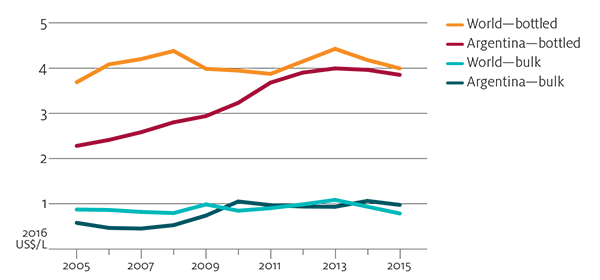

Argentina achieved a considerable increase (of almost 300 per cent) in the value of its wine exports between 2000 and 2015 by diverting production away from the low-value domestic market towards higher valued bottled wine exports. Argentina is not the only country to have pursued this strategy, but the increase in its export unit value has been significant (Figure 3).

Over the decade to 2015 the world export unit value for bottled wine increased by 8 per cent in constant dollar terms to US$4 dollars a litre (in 2016 US dollars). Argentina’s export unit value for bottled wine increased by 69 per cent over the same period as demand strengthened for the higher quality product. Over the five years to 2015, Argentine bottled wine traded slightly below the world average export unit price.

This provided a competitive advantage over Australian bottled wine, which traded above the world price over the same period. Argentina’s bulk wine export unit value remained broadly in line with the world unit price during this period (UN Statistics Division 2016).

The shift of Argentina’s wine producers towards higher value segments of the global market is partly a response to changes in global demand. However, it was also driven by the loss of export sales and declining competitiveness in the bulk wine category, where small margins limit the capacity of producers to reduce prices or absorb cost increases (USDA–FAS 2015a). Preferential trade agreements secured by competitors, like Chile’s free trade agreements with China and the European Union, accounted for some of this loss in competitiveness. However, domestic economic and political factors throughout the 2000s also played a role (Williamson 2016).

Argentina is a major competitor in all of Australia’s main wine export markets, except China. Neither Argentina nor Australia have free trade agreements with the European Union, the United States or Canada and therefore face the same import tariffs on wine in those markets. The European Union and the United States are Australia’s most important export destinations by value. The European Union is the largest export market for Australia (28 per cent in 2015), dominated by the United Kingdom, with 18 per cent. The United States accounts for 23 per cent of Australia’s export share, followed by China (17 per cent) and Canada (9 per cent).

Argentina faces strong competition in the Chinese wine market. China imposes a tariff of 20 per cent on imports of bulk wine and 14 per cent on bottled wine (WTO 2016). This puts Argentina at a competitive disadvantage to Chile and Australia, which both have free trade agreements with China. China eliminated tariffs on Chilean wine at the beginning of 2015 and Australian wine will be tariff-free by 2019 (DFAT 2015). Argentina’s cost-competitiveness in bulk wine has also decreased because the Chinese bulk wine market has become dominated by Chilean imports and growth in domestic production.

Chile

[expand all]

Domestic market

Chile’s wine industry accounts for about 7 per cent of global production, with 1.8 million tonnes of wine produced in 2013. Chile’s wine grape growing regions stretch 900 kilometres from the Elqui Valley in the north to the Malleco Valley in the south, along the western side of the Andes. Like Argentina, Chile’s wine grape growing regions are shielded from pests and diseases by high altitude and low humidity. The most common varietal wines produced are cabernet sauvignon, sauvignon blanc and merlot.

Chilean wine production grew significantly between 2000 and 2013, increasing by an average of 12 per cent a year (FAO 2016). This was the fastest rate of growth among the world’s top wine-producing nations and a result of two decades of investment in the industry. Area planted to wine grapes more than doubled and the industry increased use of imported technologies such as stainless steel fermentation tanks, trellis systems and drip irrigation. Grape yields increased from 11.5 tonnes a hectare in 2000 to 15 tonnes a hectare in 2013 (FAO 2016). Unfavourable weather conditions affected yields in 2014 (USDA–FAS 2015b).

Chile has the lowest per person wine consumption of all the major wine-producing and wine-exporting countries, at around 17 litres a person a year (USDA–FAS 2015b). That compares with 29 litres a person in Australia, 40 litres in Argentina and 55 litres in France (ABS 2015). Beer is the preferred alcoholic beverage in Chile. The expansion of the Chilean wine industry has been export focused because of low domestic wine consumption.

Exports

In 2015 Chile was the fourth-largest exporter of wine globally, shipping 877 million litres valued at US$1.85 billion. Bottled still wine accounted for over half of Chile’s wine exports (487 million litres), followed by bulk wine (386 million litres) and sparkling wine (4 million litres). The value of Chile’s wine exports peaked at just over US$2 billion in 2013.

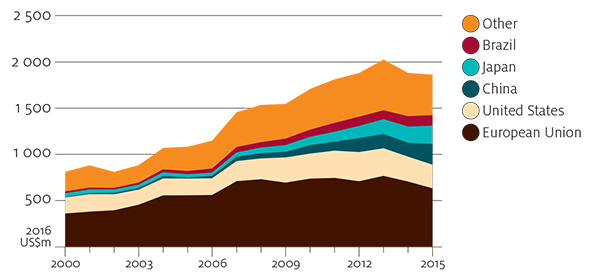

Chile’s wine exports to the European Union, its most important market by value, totalled US$630 million in 2015 (Figure 4). The United Kingdom accounted for a third of that value. The United States is Chile’s second-largest export market, accounting for 14 per cent of its exports. China and Japan have grown dramatically in importance. Together they accounted for 6 per cent of Chile’s wine exports in 2000 but 23 per cent in 2015. Brazil is Chile’s most important South American market, accounting for 6 per cent of its export share.

Source: UN Statistics Division 2016

Chile is a major exporter of bottled and bulk wine, ranking fourth globally for both by volume in 2015. Bulk wine accounted for around half of Chile’s wine exports to the European Union and the United States and for two-thirds of its exports to China.

Bulk wine is often bottled locally or blended with domestic production in China (Hornby 2016). The Chilean Government’s support for free trade has delivered significant benefits to Chile’s wine exporters. The government has established free trade agreements with all of its major wine export markets. Chile’s 2003 free trade agreement with the European Union led to the elimination of the European Union’s tariff of €3.2 a litre by 2008 (European Commission 2003). The value of Chile’s exports to that market increased by 60 per cent between 2003 and 2015. Under the 2005 Chile–China Free Trade Agreement, the 14 per cent tariff on bottled and sparkling wine and the 20 per cent tariff on bulk wine were phased out by 2015 (China FTA Network 2005).

Between 2005 and 2015, the value of Chile’s exports to that market increased more than twentyfold. Chile is only the second country to obtain tariff-free access to the Chinese wine market. New Zealand gained tariff-free access in 2012 (NZ Foreign Affairs and Trade 2008). Chile has also established free trade agreements with the United States (2004), Japan (2007) and Australia (2009).

China has also been an increasingly important market for the Australian wine industry. Australian exports to China grew at a similar rate to Chile’s exports between 2005 and 2015, despite Chile’s relative competitiveness in that market given its free trade agreement. Australian wine exports will not be tariff-free until 2019 under the China–Australia Free Trade Agreement. However, returns to Australian wine exports are higher than to their Chilean counterparts, because they trade at different price points. Between 2005 and 2015, Australian bottled still wine traded at a 42 per cent premium to Chile’s in constant dollar, weighted average terms—at around US$5.10 a litre compared with US$3.60 a litre (ABS 2016). Australian bulk wine traded at a 56 per cent premium to Chilean bulk wine over the same period. However, bulk wine does not account for a significant share of Australian exports to China by value.

Chile’s focus on improved quality is evident in not only the growth in its exports generally but the changing mix of wine exports to China. Between 2005 and 2015, the share of Chilean bottled still wine exports to China increased from 40 per cent to over 70 per cent by value, reflecting China’s growing appreciation for high-quality Chilean wine. The growing status of Chilean bottled wine, combined with its lower relative price, will continue to support Chile’s global competitiveness.

References

ABS 2015, Apparent consumption of alcohol, Australia, 2013–14, cat. no. 4307.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, available at abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@. nsf/mf/4307.0.55.001.

ABS 2016, International trade in goods and services, Australia, September 2016, cat. no. 5368.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, available at abs.gov.au/ausstats/ abs@.nsf/mf/5368.0.

China FTA Network 2005, ‘Free trade agreement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Republic of Chile’, Ministry of Commerce, People’s Republic of China, available at fta.mofcom.gov.cn/topic/enchile.shtml.

DFAT 2015, ‘China–Australia Free Trade Agreement’, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra, available at dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/chafta/Pages/ australia-china-fta.aspx.

European Commission 2003, ‘European Union–Chile Free Trade Agreement’, Brussels, available at ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/chile/.

FAO 2016, ‘FAOSTAT’, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, available at faostat3.fao.org/download/Q/QD/E, accessed 4 October 2016.

Farinelli, F 2013, Innovation and learning dynamics in the Chilean and Argentine wine industries, AAWE Working Paper no. 145—Business, December, American Association of Wine Economists, New York, available at wine-economics.org/working-papers/#110/1/list.

Hornby, L 2016, ‘Chile: turning copper into wine’, Financial Times, 20 April, available at ft.com/content/bced72c4-0608-11e6-9b51-0fb5e65703ce.

NZ Foreign Affairs and Trade 2008, ‘NZ–China Free Trade Agreement’, Wellington, available at mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements-in-force/china-fta/.

UN Statistics Division 2016, ‘UN Comtrade’, New York, available at comtrade.un.org/data, accessed 20 September 2015.

USDA–FAS 2015a, Argentina–Wine annual, GAIN Report, 31 March, Foreign Agricultural Service, US Department of Agriculture, Washington DC, available at gain.fas.usda.gov/Lists/Advanced%20Search/AllItems.aspx.

USDA–FAS 2015b, Chile–Wine annual, GAIN Report, no. CII502, 4 March, Foreign Agricultural Service, US Department of Agriculture, Washington DC, available at gain.fas.usda.gov/Lists/Advanced%20Search/AllItems.aspx.

Veseth, M 2010, ‘Secrets of Argentina’s export success’, The Wine Economist, available at wineeconomist.com/2010/06/14/secrets-of-argentinas-export-success.

Williamson, L 2016, ‘Recent developments in Argentina’s agricultural export policies’ in Agricultural commodities: March 2016, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

WTO 2016, ‘World Trade Organization Tariff Download Facility’, available at tariffdata.wto.org/, accessed 7 September 2016.

Read the report

| Document | Pages | File size |

|---|---|---|

South American wine industry – Agricultural Commodities Report, December 2016  |

9 | 1.4 MB |

If you have difficulty accessing this file, visit web accessibility for assistance.