Jonathan Wong

Key points

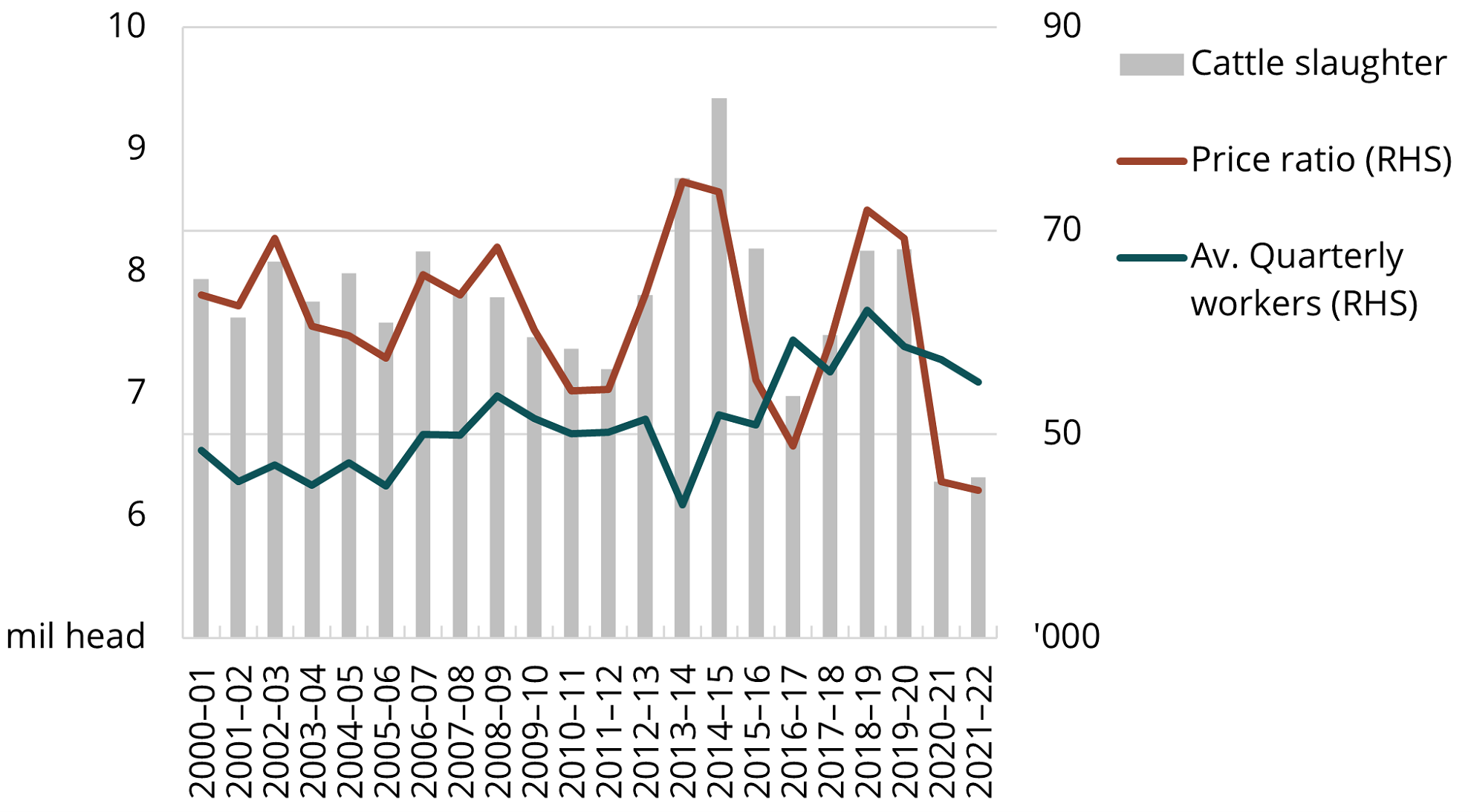

- Slaughter volumes are strongly correlated with the spread between export meat and domestic livestock prices.

- Some workforce shortages may persist, but these are unlikely to impact slaughter capacity.

- Instead, processors report stopping their least profitable activities as higher labour costs made them unviable.

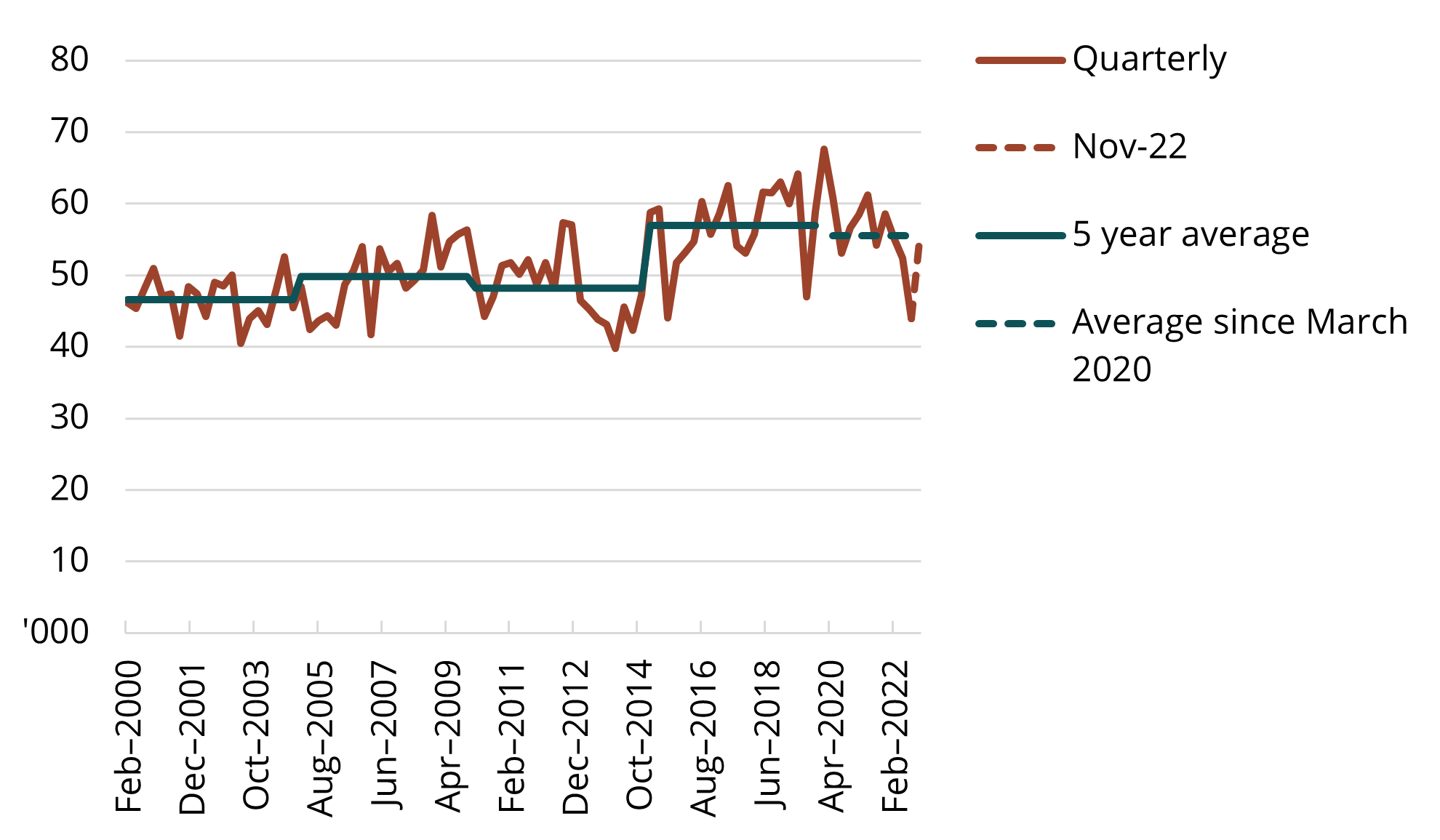

- Recent ABS data suggests the meat processing workforce is increasing.

- The meat processing industry is becoming better at adding more value per worker.

Slaughter volumes are highly correlated with the spread between export meat and domestic livestock prices. A minimum workforce is required to maintain processing capacity, and because of this, at times there is a disconnect between slaughter volumes and meat processing workforce numbers. Workforce shortages that do not threaten the minimum workforce required are more likely to result in processors stopping their least profitable activities, as the cost of labour made them economically unviable. This may impact the nature of work that can be carried out, similar to other industries faced with labour shortages. While some shortages remain, based on the assumptions over the forecast period, they are not expected to impact slaughter capacity over the medium-term. Recent ABS data also shows that the meat processing workforce appears to be increasing.

The meat processing sector has become better at adding value since the early 2000s. A growing workforce has led to more processing work being completed and ensured that greater value is extracted from each unit slaughtered. This shift has in part been facilitated by capital investment which enable workers to focus on high value processing activities, such as through more 'prime' cuts or ready to eat portions, rather than increasing volumes. Ultimately, this means that the meat processing sector will be in a better position to compete in a tight labour market when its profitability increases, as it can extract more value per unit slaughtered.

There are not expected to be any significant workforce related impacts on slaughter volumes for the outlook period through to 2027–28. While abattoirs might not be able to hire staff in the numbers or at the wage they want to, this is likely to only have a small impact on the meat processing industry.

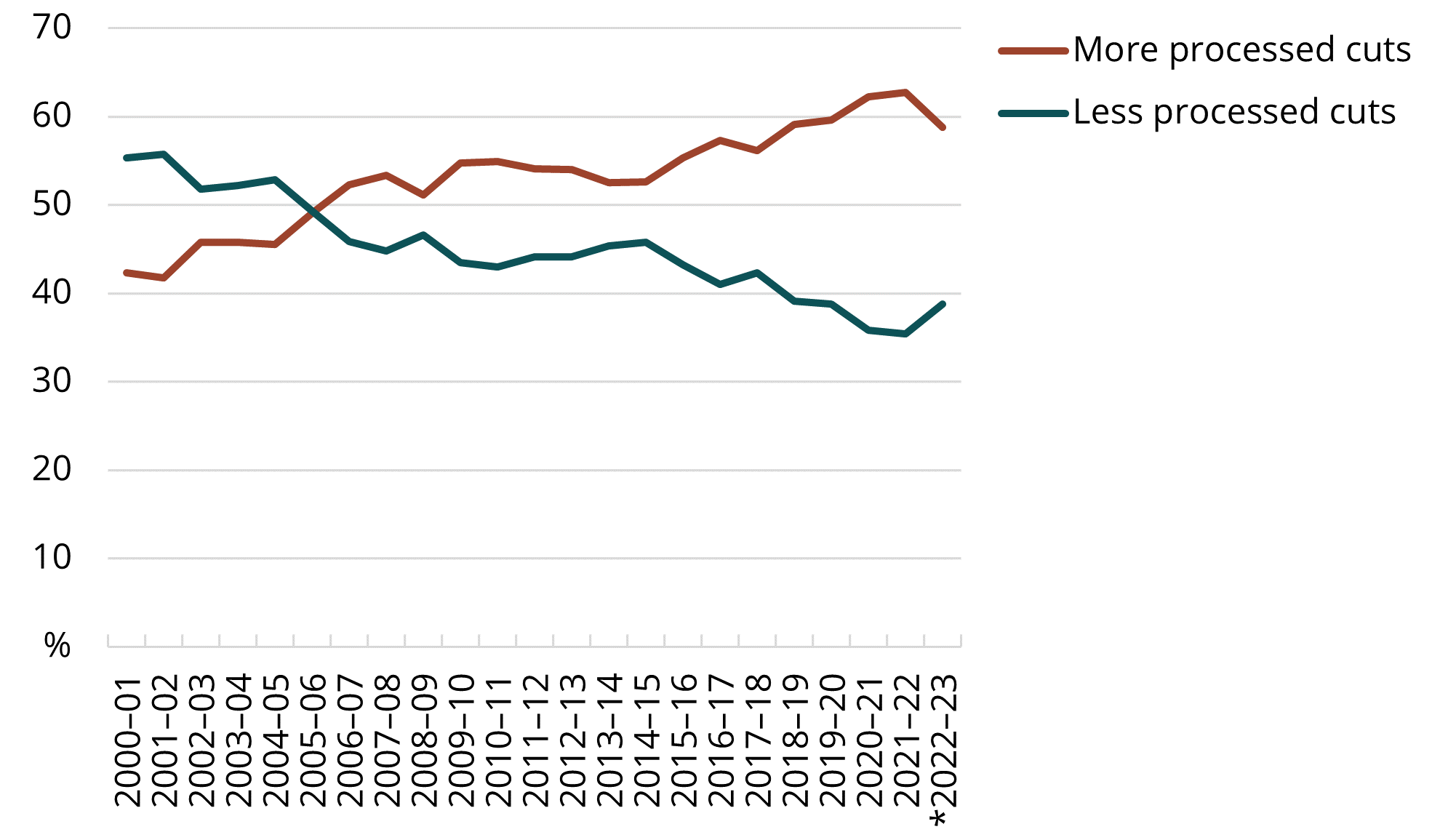

Reported shortages mean that meat processors are economising labour use across different activities to maximise value creation. This means that processors trade off the return from the time taken for further processing against the volume and return achievable from less processing. Furthermore, the least profitable activities are the first to be stopped as the cost of labour approaches the value of the activity. This effect can be seen in the falling share of 'more processed' beef exports in 2022–23. However, given that this fall has only occurred in 2022–23 and not previous years with COVID–19 border closes, this is likely due to a combination of workforce constraints and a greater price spread.

A greater price spread in a time of labour shortages is likely to incentivise production of greater volumes of less processed products, to accommodate the increasing supply of slaughter ready cattle. Figure 1.1 shows that the share of more processed beef exported has increased at a steady rate relative to the share of less processed beef. In years with a relatively abundant supply of cattle, the share of more processed cuts tends to show dips or relatively flatter periods as processors manage the trade-off between time spent and return possible.

When the price spread does improve, processors are likely to have a greater incentive to employ more workers to capture value and better manage the trade-off between processing time and return per animal. This will enable meat processors to offer higher wages in the current tight labour market.

Figure 1.1 Share of beef exports by AHECCS code, 2000–01 to 2022–23

*To December 2022

Sources: ABARES; ABS

Livestock slaughter volumes are closely correlated with the spread between meat and livestock prices. This is represented in Figure 1.2 by an export beef to young cattle price ratio. When there is a greater spread between beef and cattle prices, meat processors will slaughter more animals until the cost of slaughter approaches profit that can be made. The relationship is present, but weaker, when sheep and pigs are considered together with cattle.

Figure 1.2 Cattle slaughter and price ratio of export beef to young cattle, 2000–01 to 2021–22

beef export values to the Eastern Young Cattle Indicator.

Sources: ABARES; ABS

Despite a notable decline through the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the number of meat processing workers has recently rebounded strongly. The detailed data in the November 2022 quarter of the ABS Labour Force Survey showed the biggest quarterly growth in meat processing workers since November 2019 and the second biggest since May 2007 (Figure 1.3). While the November quarter typically shows an increase in meat processing sector workers, the unusually large increase in workers was likely due to cheaper livestock increasing the price spread, and the sector coming off such a reduced number of workers in the August 2022 quarter.

Figure 1.3 Meat processing workers, February 2000 to November 2022

Sources: ABARES; ABS

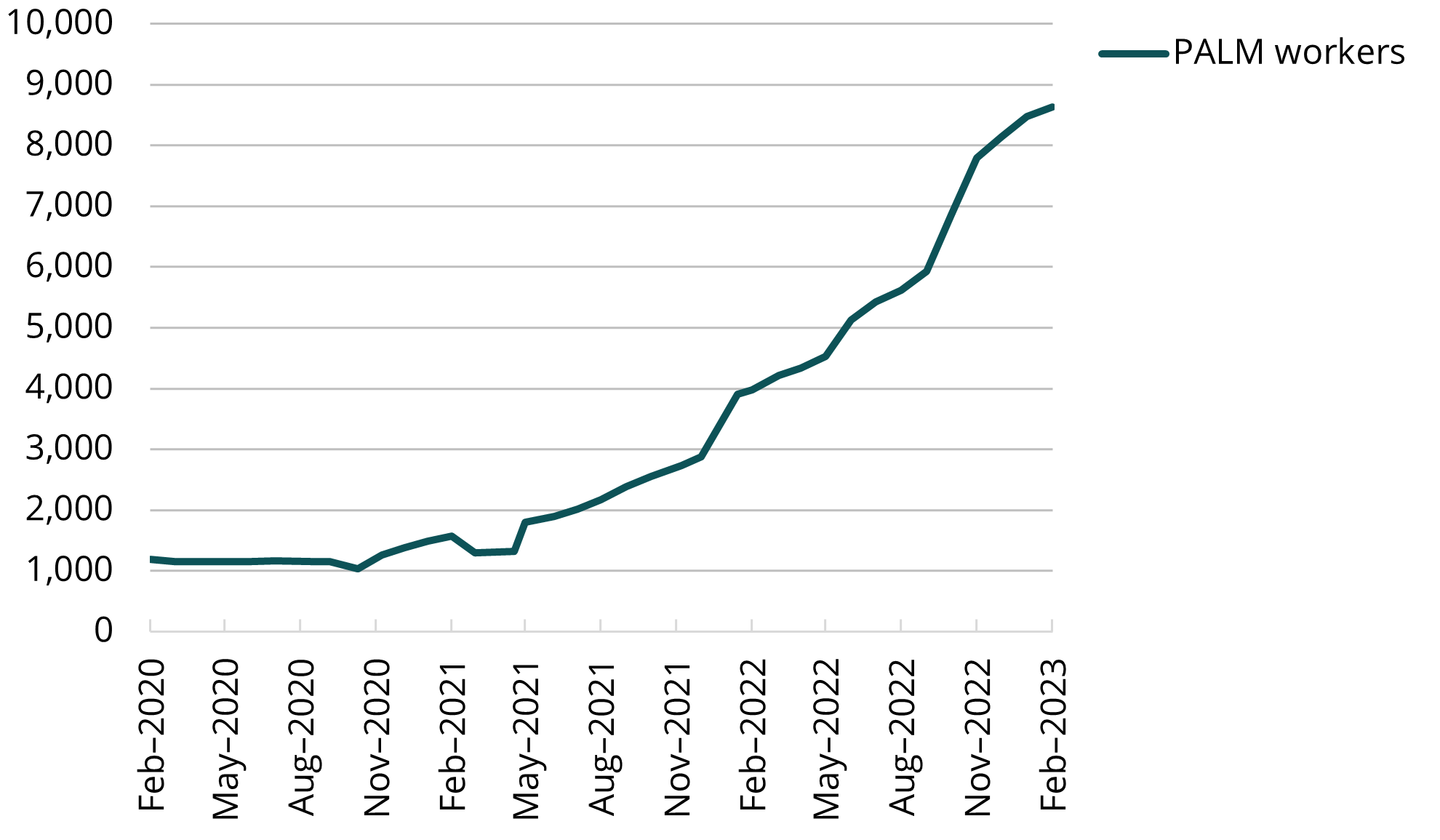

PALM workers expected to play a bigger role

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the number of Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme workers in the meat processing sector has increased significantly (Figure 1.4). This is likely to be further boosted by the announcement in December 2022 that metropolitan meat processors would also have access to the PALM scheme.

The Australian Meat Processors Corporation (AMPC) estimated workers on visas represented 13% of the meat processing workforce in 2020–21. As international travel continues to increase following the removal of COVID-19 border closures, more foreign workers are likely to become available to participate in the meat processing industry. Changes around the visa requirements for working holiday makers in northern or remote Australia mean that they have more industries they can work in, such as hospitality and tourism. However, in 2020–21, the AMPC estimated that working holiday makers represented just over 1% of the workforce.

Figure 1.4 Estimate of PALM workers in meat processing, February 2020 to February 2023

Based on the trend of lower volumes, more workers and greater value of output, it appears that workers are being used on higher value tasks. More work is now being done on additional processing to value add products before they are sold along the supply chain. The volume share of more processed cuts like frozen primal and bone in cuts relative to total exports has increased since 2000. At the same time, the share of cuts which require less processing like hindquarter and forequarter cuts has decreased (Figure 1.1). This has likely been in part enabled by the development of markets for consumers to buy ready-to-cook, pre-processed meats exported from Australia.

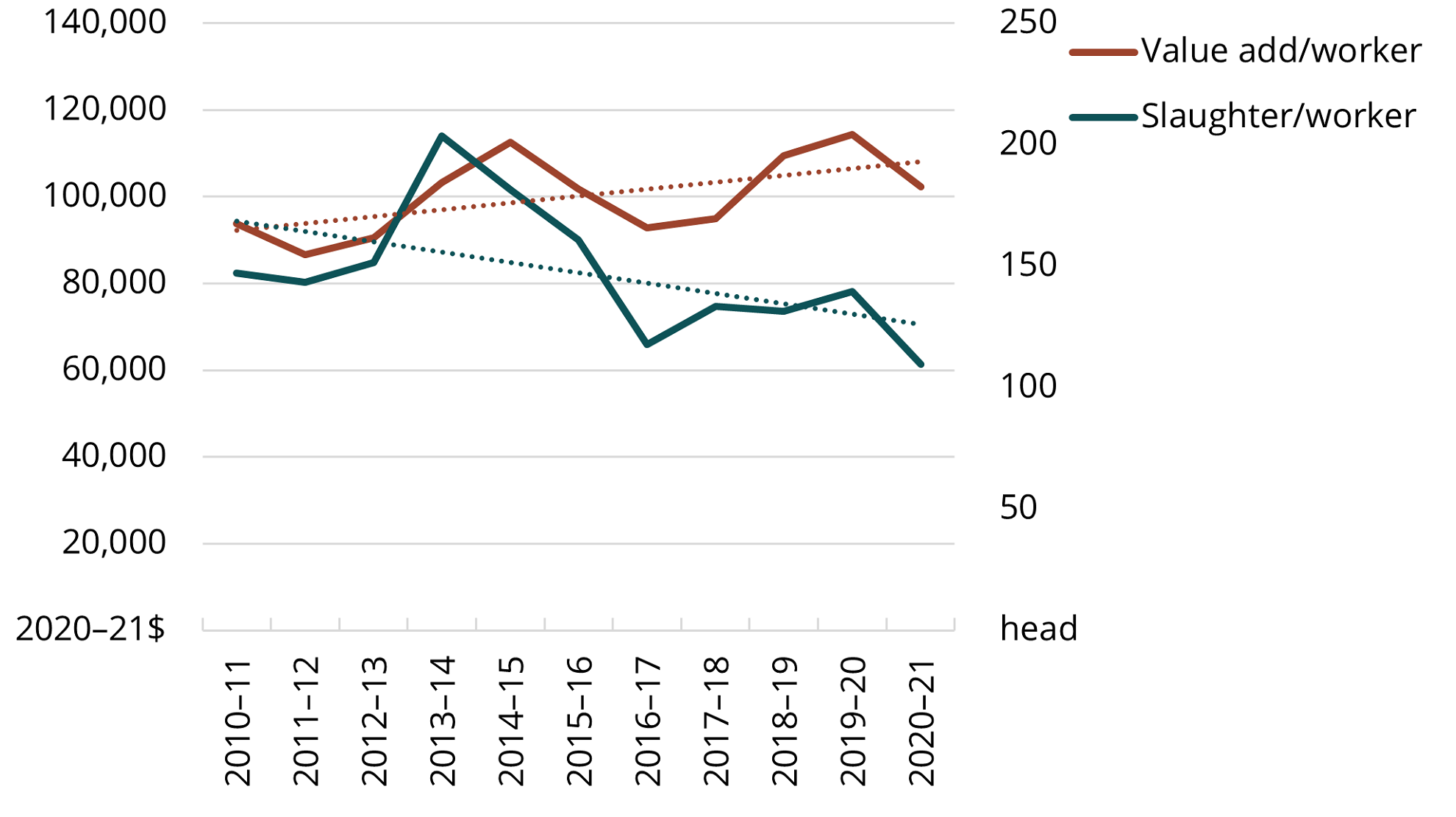

These changes have been matched with increased value adding in the meat processing industry, measured by the form of value created per worker. Figure 1.5 shows that the average value added by each worker has increased since 2010–11. Over the same period, the average number of animals slaughtered per worker has gone down.

Figure 1.5 Average value add of meat processing labour, 2010–11 to 2020–21

Sources: ABARES; ABS

In the short term, however, the amount of value added per worker typically fluctuates. In destocking years, an abundance of livestock reduces livestock prices, increasing the value added by workers. In restocking years, the difference between beef and young cattle prices falls. More expensive livestock reduce the value that can be captured by workers.