Playing to advantages

Authors: Jared Greenville, Andrew Duver and Mikayla Bruce

Introduction

Australian agriculture has benefited significantly from its focus on exports of raw agricultural and minimally transformed products. Value creation will likely continue to be driven by these exports but future opportunities across the value chain will rest on the ability to competitively trade on product attributes.

Australian agriculture has benefited significantly from its historical focus on exports of raw agricultural and minimally transformed products. Australia’s focus on these products has likely created more value for the Australian economy than would have been available from a focus on more processed products.

As we look ahead, market access, responding to emerging consumer preferences and access to imported inputs will continue to be important for maintaining value creation along with accessing new opportunities across the value chain. A key feature of the value creation landscape will be the ability to competitively trade on product attributes, such as those related to food safety and quality. In future, while new opportunities for value creation may arise downstream of agriculture, it will be crucial to take full advantage of value creation opportunities associated with trade in raw and minimally processed products, including by using digital technologies to engage customers, highlight product attributes, and communicate a compelling customer value proposition.

Industry and government both have important roles to play. Key industry roles include responding to emerging consumer preferences, and driving efficiencies through the food supply and value chains. Key Government roles include pursuing new and improved international market access, ensuring import and export regulations are effective and low cost systems, and providing an efficient and competitive business environment.

This paper summarises findings and insights from Greenville, Duver and Bruce (2020), published in the Australian Farm Institute Farm Policy Journal.

Australia’s vast natural resources and climate have contributed to it being a significant net exporter of agricultural and food commodities. In 2019–20 the gross value of farm production in Australia was $61 billion, Australian agricultural exports were valued at $48 billion (ABARES 2020a). Raw product and minimally transformed (meat) exports have made up most of Australia’s exports between 1988 and 2018 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 Export shares of raw, minimally transformed and processed products, 1988–2018

Source: UN Statistics Division

ABARES analysis shows that conditions over the last 20 years have negatively affected the profits of both cropping and livestock farms, relative to conditions experienced from 1950 to 2019 (Figure 2; Hughes et al. 2019). The effects were most pronounced in the cropping sector, amounting to an average loss in production of around $1.1 billion per year, with the frequency of negative profit years increasing to one in four years, rather than one in ten years.

While there is uncertainty about the nature and pace of future climate change in Australia, the changes are unlikely to provide net benefits to agriculture.

There has been and continues to be debate around how best to leverage Australian agriculture’s international competitiveness to generate returns for rural communities and all Australians. Such questions are central to exploring pathways for the sector to achieve its $100 billion target by 2030.

Two government reports, 20 years apart, illustrate the ongoing-but-changing nature of this debate. In 2000 the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Resources examined options to increase the value creation to Australian raw material in its Of material value? and Getter a better return reports (Commonwealth of Australia 2000, 2001).

More recently, CSIRO (2019) put forward a road map for unlocking value-adding growth opportunities for Australian food and agribusiness.

The reports point to a shift from previous attention to downstream processing as the means to grow returns (Commonwealth of Australia 2000, 2001) to contemporary attention to a mixed and consumer-centred approach (CSIRO 2019). The former view was popular in the 1980s and remains so in several areas (Griffith & Watson 2016). Despite time passing, the underlying question and debate remain similar: Is Australia missing opportunities for domestic value creation because of the focus on trade in raw products?

Value creation can come from several sources. It can occur when there is a change in the form of a product, for example, changing grain into flour. It can also occur through the addition of an attribute to a product, for example, creating a traceable supply of animals. Both types of activities generate additional returns to domestic land, labour and/or capital. The returns from the addition of attributes accrue to producers and other sectors of the economy involved in the supply chain.

The value of all types of agricultural exports is made up of more than just returns to the agricultural sector. Australian agriculture's $48 billion export value, for example, comprises contributions from a range of sectors including agriculture, food manufacturing, industrial and service sectors.

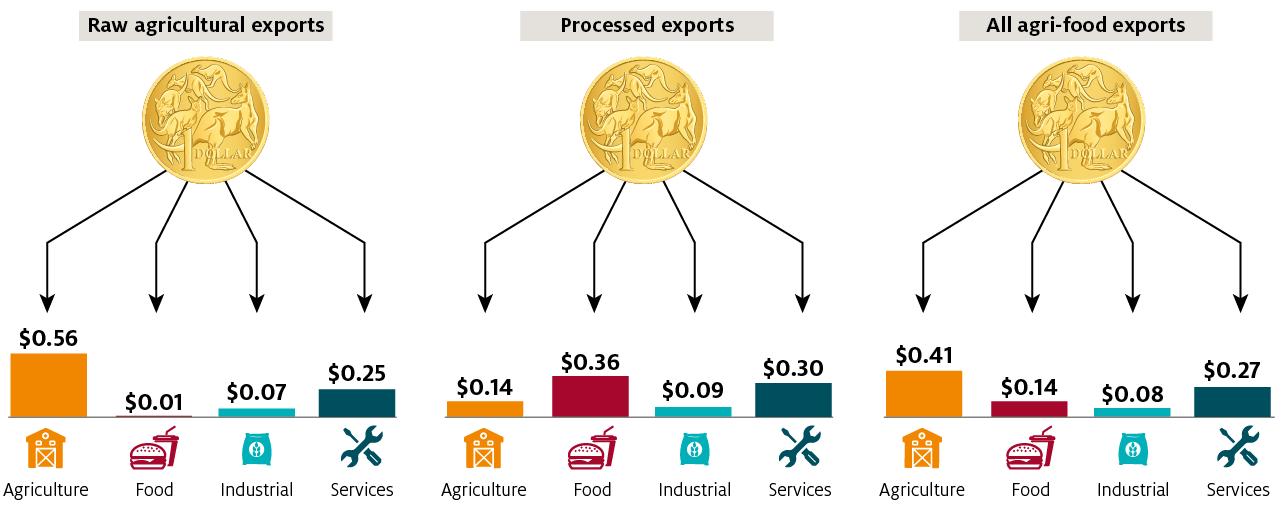

Around 25 cents of every $1 of raw agricultural export accrue to the domestic service sector for inputs, such as all business services, trade services (retail, wholesale and financial) and transport. Around 7 cents go to the domestic industrial sectors for inputs related to chemicals, plastics, fertilisers and fuel (Figure 2). The majority of the rest, 56 cents, go to the agriculture sector itself.

FIGURE 2 Composition of Australian export value by sector, 2014

Source: Data derived from Greenville, Kawasaki & Jouanjean (2019b)

Value is also created from the use of foreign inputs. On average, in 2014 around 11% of the value of raw agricultural exports from Australia was made up of foreign inputs. The result was similar for food exports.

Without accounting for where jobs are created, comparisons between the value content of raw versus processed products show that the return from $1 of exports to the Australian economy is the same—around 90 cents in every dollar.

The agricultural trading environment has improved since the WTO’s Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) came into force in 1995. Globally, agricultural tariffs, subsidies and other forms of protection have fallen. This positive trend has been the result of the accession of new countries to the WTO (most significantly, China) and the rapid increase in free trade agreements (OECD 2016; Duver and Qin 2020). The latter has both decreased average applied tariffs and extended provisions on agricultural trade beyond that of the AoA (Thompson-Lipponen & Greenville 2019). These changes have seen a continued and strong growth in agri-food trade (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 Global agri-food trade has grown and applied tariffs fallen

As the global trading environment has improved, agricultural and food trade has become increasingly specialised and more often includes multiple parties. The final product on supermarket shelves or consumed in restaurants and cafes is often produced in different stages, across multiple industries and in different countries. The increasing focus on specialisation of production has created a supply chain that spans across countries and is termed a 'global value chain' (GVC) (Greenville 2019). It has also significantly increased competitive pressures on processors.

Greater competition and global value chains have created more opportunities for Australian raw product exports. Primary producers have benefited from increased global competition between processors who often derive competitive advantages from proximity to a large base of end consumers. This has provided opportunities for higher export volumes and value creation opportunities as final product prices have fallen and processors have reached more customers.

Global competition between processors is likely to increase over time due to the pressure from increasingly fragmented production systems. In contrast, primary production is less likely to face increased competition from fragmentation because of the reliance on land and climate.

On-farm production practices are changing to meet consumer demands, which have led to the addition of attributes to raw products. Attributes include aspects such as traceability and organic production, along with meeting market requirements set by non-tariff measures. Generally, these additional attributes require additional inputs. While these additional inputs may increase the cost of production, they also generate higher returns to agriculture and other sectors of the economy. In this way, they create domestic value akin to activities like domestic processing. Past research points to the increased service content in exports as evidence of an increase in such value-adding opportunities (Greenville, Kawasaki & Jouanjean 2019a).

Changes in global markets and the need to meet consumer preferences through raw product attributes mean there is no clear link between further domestic processing and additional value creation in exports for an economy. For countries that hold a competitive advantage in agricultural production, changes in the global trading landscape have furthered the benefits and value creation opportunities from raw product exports.

Globally, the biggest driver of growth in gross value-added for agricultural sectors between 2004 and 2014 came from the export of raw products (Greenville, Kawasaki & Jouanjean, 2019a). Raw products were the main source of export growth for 86 of the 141 countries and regions (Table 1).

Those countries experienced stronger growth in agricultural domestic value-added than those focused on processed products—42% growth compared to 21% growth. A larger share of exporters of raw products than of processed products also had positive growth in the value of agricultural products over the period—72% versus 60%. Australia was one of the countries where agricultural domestic value creation was greater in raw products and had overall growth in total agricultural returns from exports.

TABLE 1 Growth in real domestic value derived from exports across 141 countries and regions, 2004–2014

| All countries | Those with positive domestic value trade growth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Average growth | No. | Average growth | ||

| Raw material focused | 86 | 42% | 62 | 66% | |

| Processed product focused | 55 | 21% | 33 | 55% | |

| Those with overall growth in domestic value of exports | 95 | 62% | 95 | 62% | |

Note: Growth in real value calculated by deflating nominal values by the IMF food price index.

Source: Greenville, Kawasaki & Jouanjean (2019a)

Growth in agricultural returns from exports are only part of the domestic value-creation story. Value creation is more generally about creating additional jobs and income for Australians prior to a product being exported. Total domestic value creation related to agricultural production must consider returns to all sectors of the economy.

Greenville, Duver and Bruce (2020) outlined a method to contrast value creation between countries that focus on raw product exports and those that focus on processed exports. They sum all agricultural and non-agricultural value in exports from agriculture and food processing sectors, along with domestic agriculture value in other non-food sector exports (such as that included in pharmaceutical and textile exports). It provides a measure of total export returns enabled by agricultural production and makes it possible to examine the aggregate domestic value return delivered from exports on every $1 of agricultural production. The analysis shows that domestic value creation opportunities for a given $1 of agricultural production created by raw product exports are as great, if not greater, than those of more processed exports (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4 Domestic value creation multiplier for every $1 of agricultural production for countries focused on raw product exports versus more processed exports

Source: Greenville, Kawasaki & Jouanjean (2019a)

Raw product exports being the main driver for domestic value growth in the past does not mean that opportunities for domestic value creation by downstream sectors do not exist. It also does not suggest that it is not worth exploring any opportunities for creating downstream processing industries. Gains from a move downstream, however, will need to be weighed against the value that already exists in exporting raw products. Past studies examining the competitiveness of Australian industries at various stages in the value chain have generally found that international competitiveness decreased progressively with each additional processing stage (Mosoma 2004).

Addressing value creation downstream requires addressing the underlying competitiveness challenges of those downstream industries and identifying those factors that sit with government. It is more efficient for business to determine what to produce and where to sell.

There are examples where value creation from a shift to downstream activities has occurred in Australia—infant milk formula and wine are such examples. With infant milk formula and dairy exports more generally, there are additional factors that have created a situation where Australia is competitive (Figure 5).

The sector has leveraged both its reputation for food safety (additional market service and regulatory inputs into production) along with access to imported inputs (dairy products from New Zealand), in combination with domestic production, to create value. Some of these reputational attributes, like food safety, are likely to be a source of growing demand post COVID-19 (Greenville, McGilvray & Black 2020).

FIGURE 5 Selected Australian dairy exports, 2000–01 to 2019–20

Source: ABS 2020

In general, access to imported agricultural inputs are a key feature of growth in domestic food sector value. Greenville et al. (2017b, 2019b) found that countries that had higher shares of foreign value in exports, and which had a greater diversity of imported suppliers, grew domestic value faster than those which were more domestically focused. Imports can also help smooth any domestic production variability caused by Australia’s variable climate.

For Australian policy makers and industry, there are a few considerations around creating further domestic value from Australia’s competitive agricultural base.

- Market access, responding to emerging consumer preferences and access to imported agricultural products and other inputs will be important features for accessing these opportunities. Pursuing new and improved market access and lowering the cost of importing are key roles of government.

- The government's role in supporting a move towards downstream processing is less clear. Government intervention through subsidies or incentives does not necessarily lead to value creation and can distort the competitiveness of firms and harm international reputations. The government can focus on removing regulatory barriers and reducing red tape to assist with competitiveness.

- While certain attributes can be value-creating, they are also subject to international competition, making wider pro-competitive reforms and best-practice regulation part of the basis for maximising value creation.

Achieving competitiveness through innovation or product differentiation can be a way to increase profits in the future. However, it comes with significant research and development costs and requires access to lowest cost imports. The underlying drivers of competitiveness extend to seeking out new opportunities from both upstream and downstream attributes, which will require some clarification of the roles of government and industry.

Investment in assurance and other systems, for example systems that underpin traceability, will continue to be important and allow the sector to meet consumer expectations. The 2020–21 budget contained provisions to support the underlying competitiveness of agricultural exports through the Busting Congestion for Agricultural Exporters measure. This measure will modernise the Australian export meat inspection and regulatory system by providing a robust regulatory system that enhances the reputation for high‑quality and safe Australian products.

Ultimately, the priority should be to have a competitive and open economy. This will allow resources to be allocated effectively to their highest value use in competitive markets where private enterprises can determine what to produce and where to sell.

It seems likely that trade in raw and minimally processed products will continue to provide the largest and most important value-creation opportunities for Australian agriculture in coming decades.

Despite volatile production years, the production of primary products by Australian farmers is intrinsically tied to our geography and natural endowments.

These attributes cannot easily be traded and therefore contribute significantly to Australia’s competitive advantage in GVCs. Further investment in inputs to transform undifferentiated primary products into more specialised products, such as varieties with differentiated attributes, could also create additional export value.

Ultimately, Australia must rely on competitiveness achieved by its own endowments, production efficiencies, and the quality and reliability of its products. Policy makers and industry should be aware that a move downstream is not a precondition for increasing domestic value creation and that Australia is not missing out on value creation through its focus on raw and minimally processed products. While there might be some marginal improvements for some industries, value creation can be unlocked by pro-competitive reforms along the supply chain and ensuring production is consumer focused. Both these elements allow additional value-creating opportunities both at the farm gate for raw products and further downstream.

ABS 2020, Information Consultancy Service, 2007, cat. no. 9920.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

ABARES 2020a, Agricultural commodities: June quarter 2020 – Statistics – data tables, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

Commonwealth of Australia 2001, Getter a better return: Inquiry into increasing value added to Australian raw materials, House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Resources, Canberra.

Commonwealth of Australia 2000, Of material value? Inquiry into increasing the value added to Australian raw materials, House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Resources, Canberra.

CSIRO 2019, Food and Agribusiness: A roadmap for unlocking value-adding growth opportunities for Australia, CSIRO, Canberra.

Duver, A & Qin, S 2020, Stocktake of Free trade, competitiveness and a global world: How trade agreements are shaping agriculture, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

Greenville, J 2020, Analysis of government support for Australian agricultural producers, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

Greenville, J 2019, Australia's place in global agriculture and food value chains, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

Greenville, J, Duver, A & Bruce, M 2020, Playing to advantages: Raw agricultural product exports driving value creation in Australia, Australian Farm Institute, Farm policy journal, Surry Hills, Australia.

Greenville, J, McGilvray, H & Black, S 2020, Australian agricultural trade and the COVID-19 pandemic, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra.

Greenville, J, Kawasaki, K & Jouanjean, M 2019a, Value Adding Pathways in Agriculture and Food Trade: The Role of GVCs and Services, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 123, OECD Publishing, Paris,

Greenville, J, Kawasaki, K & Jouanjean, M 2019b, Dynamic Changes and Effects of Agro-Food GVCS, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 119, OECD Publishing, Paris,

Greenville, J, Kawasaki, K & Beaujeu, R 2017b, How policies shape global food and agriculture value chains, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 100, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Griffith, G & Watson, A 2016, Agricultural markets and marketing policies, Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 60, pp. 594-609.

OECD 2016, Evolving Agricultural Policies and Markets: Implications for Multilateral Trade Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Mosoma, K 2004, Agricultural competitiveness and supply chain integration: South Africa, Argentina and Australia, Agrekon, Agricultural Economics Association of South Africa, South Africa.

Thompson-Lipponen, C & Greenville, J 2019, The Evolution of the Treatment of Agriculture in Preferential Trade Agreements, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 126, OECD Publishing, Paris.

UN Statistics Division 2020, UN Comtrade Database, United Nations, New York.